Have you heard of a dish called ‘choup’? It is nothing but a more dilute, soup-like version of an American dish called chili. The meat version has beef in it, but the veggie version is made with red kidney beans (rajma) and vegetables like celery, green bell peppers, carrots and onions. How did it originate? Well, one woman making chili added a little too much water and so was the ‘chili-soup’ or ‘choup’ born. Who was that woman? Well, it was yours truly.

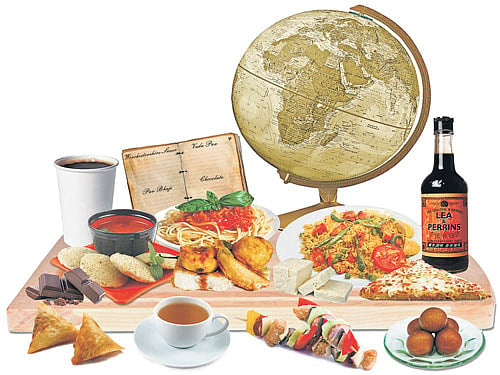

Okay, now you know the origin of a trivial dish. But how about the particular food item on your plate? Have you ever wondered about how or where your favourite food originated, or even about the origins of cooking?

First off, why did Man begin to cook his food? Because it made it tastier, of course! And Man is not the only one to think so. Recently, an experiment with chimpanzees showed that they prefer eating a cooked potato to a raw one, and will even give up raw food in order to obtain the tastier cooked version. Since we evolved from chimps, we may have inherited the love of cooked food from them. Today, we have a wide variety of foods to choose our daily meal from. But where and how did these food combinations originate?

The answer is complicated. It is very easy to trace some foods to their original homes (like my ‘choup’), but there are so many others that are lost in the mists of Time. However, this gives rise to legends which are frankly far more interesting than dry, verifiable facts.

To begin with, let’s start off with our popular beverages. Tea, as everyone knows, originated in China. Earliest records of tea drinking date to the 10th century BC. In a medical text written by Hua Tuo in the third century AD are the immortal words ‘to drink bitter t’u constantly makes one think better’.

However, coffee has a more appealing story. The legend starts with Kaldi, a goatherd who lived in the highlands of Ethiopia, where coffee trees grow. He discovered coffee after observing that his goats became more spirited after eating berries of a certain tree and would not sleep. He reported this to the abbot of a local monastery, who made a drink with the berries and used it to stay alert during long evening prayers. Today, it kick-starts our brains that are groggy in the mornings.

A tasty treat made with bread that also includes the goodness of vegetables — yes, it is the omnipresent sandwich. The concept of meat and other foods between two pieces of bread is not new. Since ancient times, scooping up or rolling up meat and other edibles in flat bread like the Jewish Matzah or rotis was prevalent throughout Western Asia and Northern Africa. In the Middle Ages in Europe (between 5th and 15th centuries), thick slices of stale bread called trenchers were used as plates. After a meal, the food-soaked trenchers would be fed to the poor or to dogs. However, the story of the modern sandwich is more colourful.

During the very late hours of a night in 1762, an English nobleman named John Montagu, the Earl of Sandwich, was too busy gambling to stop for a meal. He ordered a waiter to bring him roast beef between two slices of bread, so that his fingers wouldn’t get too greasy to play cards. As the idea became more popular with the British aristocracy, he became immortalised as the originator of the first sandwich.

Go to any store, and you’ll find the most tempting snack arranged right next to the cashier. That’s right, it is chocolate. But how did it evolve? Well, the Mayans and Aztecs of Mexico used to make a drink called ‘Xocolatl’ from the beans of the cocoa tree. The Aztec Emperor, Montezuma, apparently drank Xocolatl 50 times a day from a golden goblet as an aphrodisiac. Spaniards, who conquered Mexico, brought chocolate in its drinkable form to Europe and England. It was drunk at a royal wedding in France in 1615, and in England in 1662. Eating chocolate was unpopular when it was introduced in 1847 by Fry and Sons in England, since it was too bitter. In 1874, Daniel Peter, a famed Swiss chocolatier, stumbled upon the perfect additive to make chocolate more palatable — milk — and the familiar taste of chocolate came into being.

Popular pizza

Pizza is a favourite of many people. It first originated not in Italy, but in the Middle East during ancient times, when people ate bread topped with olive oil and native spices. But today’s version, the flat bread topped with tomato sauce and cheese, did originate in Italy, Naples to be more exact. By 1830, the Antica Pizzeria Port’Alba of Naples had become the first true pizzeria, and it remains open even today. In 1889, the baker Raffaele Esposito of Naples created a pizza in the three colours of the Italian flag — green of basil leaves, white of the mozzarella cheese and red of tomatoes — for Queen Margherita of Italy. It was a hit with her, and remains a favourite throughout the world.

And of course, pasta originated in Italy, right? But some researchers have it that pasta was introduced to Italy from China in the 13th century by Marco Polo. It was probably derived from noodles, which are unquestionably from China. In fact, the remains of the oldest noodles were found in a pot on an archaeological site on the Yellow River — it was about 4,000 years old! It was made, not from wheat flour like it is today, but out of grains of millet grass. However, the International Pasta Organisation (yes, there is truly one) contends that pasta dates back to ancient Etruscan civilisations in Italy, and therefore it is Italian in origin.

Meanwhile, the iconic Chinese dish, chop suey, may not be completely Chinese in origin, but American, instead. The dish, based on tsap seui or ‘miscellaneous leftovers’ common in Taishan, a county in Canton, may have been brought to the US by immigrant workers. This later became the famous chop suey of small-time restaurants in the western world.

However, the Chinese fortune cookie, that is served along with the bill at Chinese restaurants, is certainly not of Chinese origin; it is Japanese. Japanese tsujiura senbei or ‘fortune crackers’ are generally flavoured with sesame and miso, and they are larger and browner than their American cousins, but they hold paper fortunes too.

Now for the strange story of Worcestershire sauce. It bears the name of a place in England, yet it has a very Indian origin. Legend has it that an English nobleman returned from Bengal having fallen irrevocably in love with Indian spices. In England, he hired two chemists, John Lea and William Perrins, to recreate a Bengali recipe that he’d acquired. Lea and Perrins made up the concoction containing anchovies (a type of fish), tamarind, and vinegar among other things, but found it awful. Instead of throwing it away, they left it in a barrel in their basement. When they came back much later (months/years), they found that it had fermented and become awesome. It got its name because it was first bottled at the Lea and Perrins pharmacy in Worcester.

Indian foods turn out to have far more interesting origins. Throughout the world, ‘curry’ means a dish made of meat or vegetables and spices, of Indian origin. Some people say the word originates from the Tamil word ‘kari’ or spiced sauce, while others say it is from the French word ‘cuire’, meaning to cook. Whatever the origin of the name, the use of curries appears to be ancient. Traces of cooked ginger and turmeric were found in starch grains in human teeth and a cooking pot in the ancient town of Farmana, west of Delhi, and dated between 2500 BC and 2200 BC. This could be a ‘proto-curry’ or curry precursor in India’s ancient Indus Valley Civilisation.

This being said, there are many foods that you will swear are Indian in origin, but are not actually.

Many people consider a wedding to be incomplete without a biryani. In fact, the word ‘biryani’ comes from the Persian word ‘birian’, which means ‘fried before cooking’. According to legend, Mumtaz Mahal, Shah Jahan’s queen, once visited army barracks and decided that the men looked undernourished. So she asked the chef to prepare a special dish that could serve as a whole meal, and the biryani was born.

Ours truly...

Paneer too is a Mughal introduction. It was accidental invention that happened when Mongols carried milk in mushkis (bags made of raw hide) over long distances of desert. The heat and the rennet in the hide turned the milk into paneer. It tasted great, and thanks to them, we have wonderful dishes made from it today.

Samosa means Indian food, doesn’t it? But it was actually introduced to us from Central Asia. Various traders used to travel to India from Central Asia, and carrying heavy food was hard. So they started cooking small, crisp triangles filled with mince called ‘sambosa’ that could be eaten easily. This was adopted as samosa by Indians, and since potato works great as filling, it can be relished by vegetarians also.

Kebabs were also invented as carry-along food in Turkey during the Medieval Ages. The word ‘kebab’ itself means ‘skewered grilled meat’ in Turkish. Soldiers cut up meat into small pieces, grilled them and ate them with bread. This saved meat, and was also easy to cook.

Two other Persian imports are gulab jamoon and jalebi. Yes, both these Indian dessert table staples are totally from outside. In the Mediterranean and Persia, the dessert made of deep-fried dough balls soaked in honey syrup and sprinkled with sugar — our gulab jamoon — is called luqmat al qadi. And the jalebi is called zalabiya in Arabic and zalibiya in Persian.

If there is one dish that can claim to be a East-meets-West success story, it is the vindaloo. The word vindaloo, a Goan dish, comes from the popular Portuguese dish carne de vinha d’alhos, which is meat marinated in wine-vinegar and garlic. It was brought to India in the 15th century by Portuguese explorers. Since there was no wine-vinegar in India, Franciscan priests fermented their own from palm wine. They also added local ingredients like tamarind, black pepper, cinnamon and cardamom, as well as an American import, hot chillis.

Vada pav and pav bhaji are both fast foods that came out of Mumbai. Pav bhaji was created out of ingredients left over from other menu items by an unknown genius. Meanwhile, the invention of vada pav is credited to a snack vendor named Ashok Vaidya who ran a street stall outside Dadar Station.

Sambhar is so ubiquitous in South India that it is used as a derogatory term meaning commonplace. Actors of the past, M G Ramachandran and Sivaji Ganesan, used to refer to a fellow actor, Gemini Ganesan, as Sambhar, since his acting lacked histrionics. However, this commonplace dish has a wonderful story behind it. Cut to the Maratha kingdom in Tanjore. Shahuji, one of the rulers, loved a dish called amti which contains kokum. However, one particular season, kokum, which was imported from the Maratha homeland, ran out of supply. At that point, one brilliant person suggested that tamarind pulp that the locals used might be used instead. Shahuji experimented with toor dal, vegetables, spices and tamarind, and served the dish to his cousin Sambhaji, who was visiting him. The court loved it so much that they created a whole supply, and named the dish ‘Sambhar’ in honour of the visiting dignitary, Sambhaji.

When sambhar comes, can idli be far behind? Actually, the origins of idli are murkier than its batter. There are people who swear that idli is an import. They say that India did not use fermentation or steaming in their cooking in the old days. Xuang Zang, the Chinese traveller (7th century AD), categorically stated there were no steaming vessels in India. K T Acharya, an eminent food scientist, writes that idli-making was taught to us by the Indonesians. According to him, Hindu Indonesian kings came to India to find brides, and their cooks brought their fermentation and steaming techniques with them. Their dish was called kedli.

Meanwhile, some maintain that Gujarati silk weavers brought idli to South India, because Gujarat has Idada which is steamed dhokla made from the same ingredients as idli.

The earliest reference to what might be idli is found in Vaddaradhane, the Kannada writing of Sivakoti Acharya in 920 AD, where there is a mention of iddalige. Someshwara III, the Western Chalukya king and scholar who ruled part of Karnataka and wrote an encyclopaedia, Manasollasa (1130 AD), describes a food called iddarika.

There are also some people who suggest that there are numerous leaf-based steam-cooking of rice dishes in Tulu culture. Tulu rice dishes like moode, gunda, and kotte could be the ancestors of modern idlis, and therefore idli could have originated in Karnataka. Incidentally, the earliest Tamil work to mention idli as itali is Maccapuranam, as late as the 17th century.

Incidentally, the rava idli was born in Mavalli Tiffin Rooms (MTR) of Bengaluru. According to MTR, during World War II, the rice used in making idlis was in short supply. So, they experimented with semolina or rave, and voila, a new dish was born.

A lesson to take away from this delving into the history of food is that food is something that is constantly evolving. Who knows, one day somebody may look into the origins of the popular dish ‘choup’...