Like any community, Tamil Brahmins have their own quirky customs and practices that are rarely captured in literature. You come across references to them in R K Narayan, embedded without labels and understood only by the Tambrams, as some would like to call the community, and perhaps in some translated works.

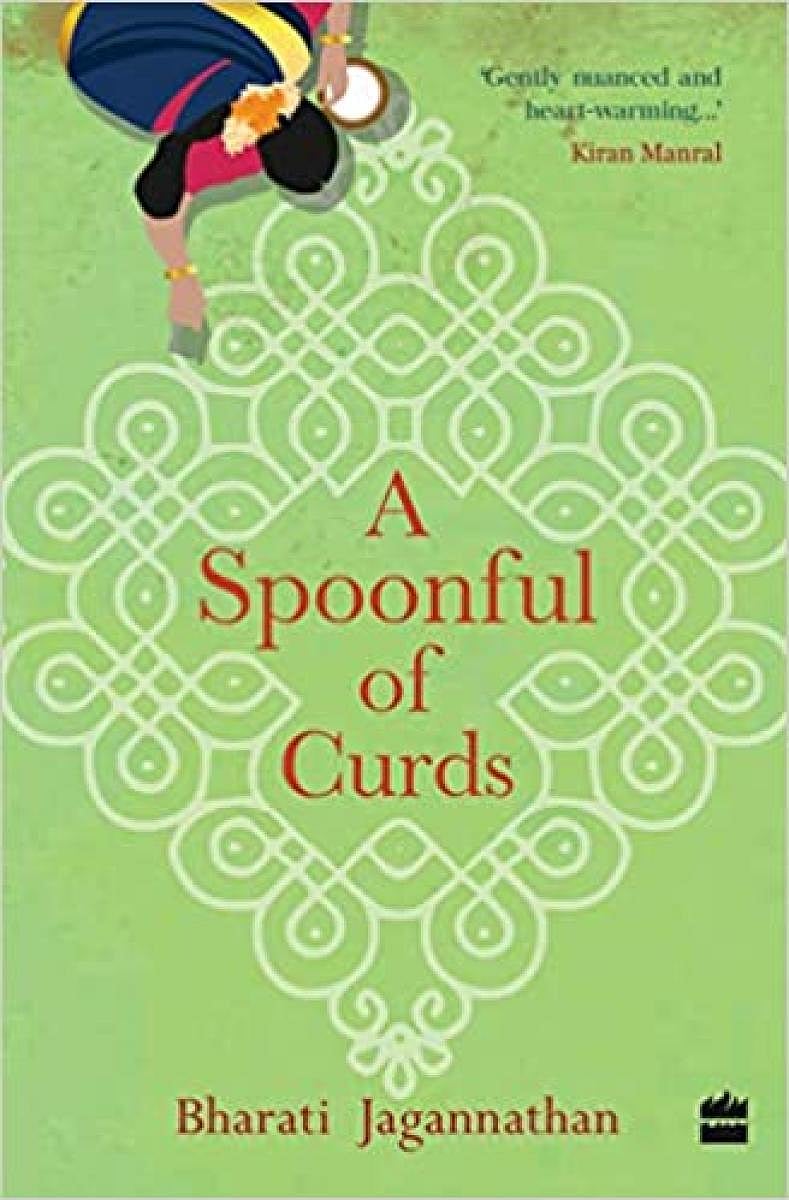

But Bharati Jagannathan’s short story collection, ‘A Spoonful of Curds’, not only jogs the memory about some of the rapidly disappearing aspects of the so-called Tambram lifestyle, but also examines how their pious and ritual-filled existence is coping with the tsunami of modernity and progress that drove them away from home into pockets of north India and overseas.

The fact that Bharati isn’t setting out to produce stereotyped portraits of the community is apparent from their women-centredness. Almost all the 13 stories capture how women handle expectations of a conservative family and how the changed environment has empowered some of them to break free.

A canvas of customs

Bharati sets the reader’s expectation high with the first story 'Grihapravesham', in which Viji, who returns to her parent’s home in Delhi after six months of torture by her husband, finds her life contrasting with that of her friend and neighbour Renuka, who decides to break her 20-year marriage over an affair her husband had years ago, after long contemplation. With Renuka’s mother passing away and Viji’s parents ageing, the two women look forward to a future of companionship in old age. Not until you pass a hundred pages and finish the story 'The Prime Of Janaki Ammal' do you actually start wondering if Renuka in the first story was hinting at something more intimate than friendship.

The stories look bolder as Bharati paints them in the canvas of old customs and idiosyncrasies unique to Brahmin households. The ‘Athai Pati’ (in ‘A Match For Meenatchi’), the grandaunt so ubiquitous in the families, who insists on home remedies and steadfast practice of customs, is an all too familiar character; a version of her would’ve existed in many traditional families.

Also familiar is the meticulousness of the grandfather in 'In Memoriam', in reading the obituaries and investigating if the deceased was someone he had known in the past. The bunch of old invitations and portraits of gods from old calendars may represent a life well lived, while also hinting at the futility of memory itself, especially as they would die with the person.

Even in a story that is nothing more than a poignant portrait, Bharati ventures to show how it’s women, as they shrink into a corner in old age, are the ones to recognise the changed environment of their grandchildren.

“‘The world is not the same’,” the grandmother remonstrates her elderly husband in ‘In Memoriam’. “Today, they can even replace a person’s heart and tomorrow our own Gayatri might invent something new. Young people nowadays learn all kinds of things that didn’t exist when you went to college.’”

A candid take

The struggles of women also vary from the enormous — managing a husband and a lover in ‘Guilt’ — to the transient, but no less grave such as in ‘Night Bus To Srivilliputhur’, where a young Delhi-based reporter has to debate going to a public toilet, despite the urgency.

The candidness with which Bharati broaches the subject of sex in both ‘Guilt’ and ‘In Black And White’ is refreshing. Even in the apparently modernised community, sex still remains a taboo that could, at best, be referred to in arcane euphemisms. Despite the audacity of her imagination, Bharati approaches the subject with sensitivity in these two stories.

But ‘Lavender Orchids’ and ‘The Prime of Janaki Ammal’ are in a different league. Not just because the author, rather uncannily, introduces the reader to cross-dressing and lesbianism, but also in the way she challenges us to glimpse how modern environments could empower people to be themselves.

For instance, could Janaki Ammal, who observes the age-old custom of letting her son snap the nuptial thread 10 days after her husband’s passing to announce her widowhood, shield her granddaughter and her lesbian partner from the unforgivingly severe family? Should Varsha have told her mother that Ashok’s cross-dressing can’t be a secret any more and she actually means to break her marriage (although her mother thinks its postpartum depression)?

Lighthearted too

Presenting unconventional situations doesn’t mean the author sacrifices lightheartedness. Imagine a daughter, years after turning single, toying with the idea of her 63-year-old mother marrying a retired brigadier and living as a wife in his house? The author plays around with the deliciousness of the irony as the mother, despite her firm belief in the world being an illusion, is the one who considers the love interest from her ex-officer friend.

Despite the boldness of the imagination, Bharati doesn’t come across as a dissenter or as someone too insensitive to traditions. Closing down this book, you won’t disrespect customs and conventions, but understand that they would continue to linger at least as a connect to the past.