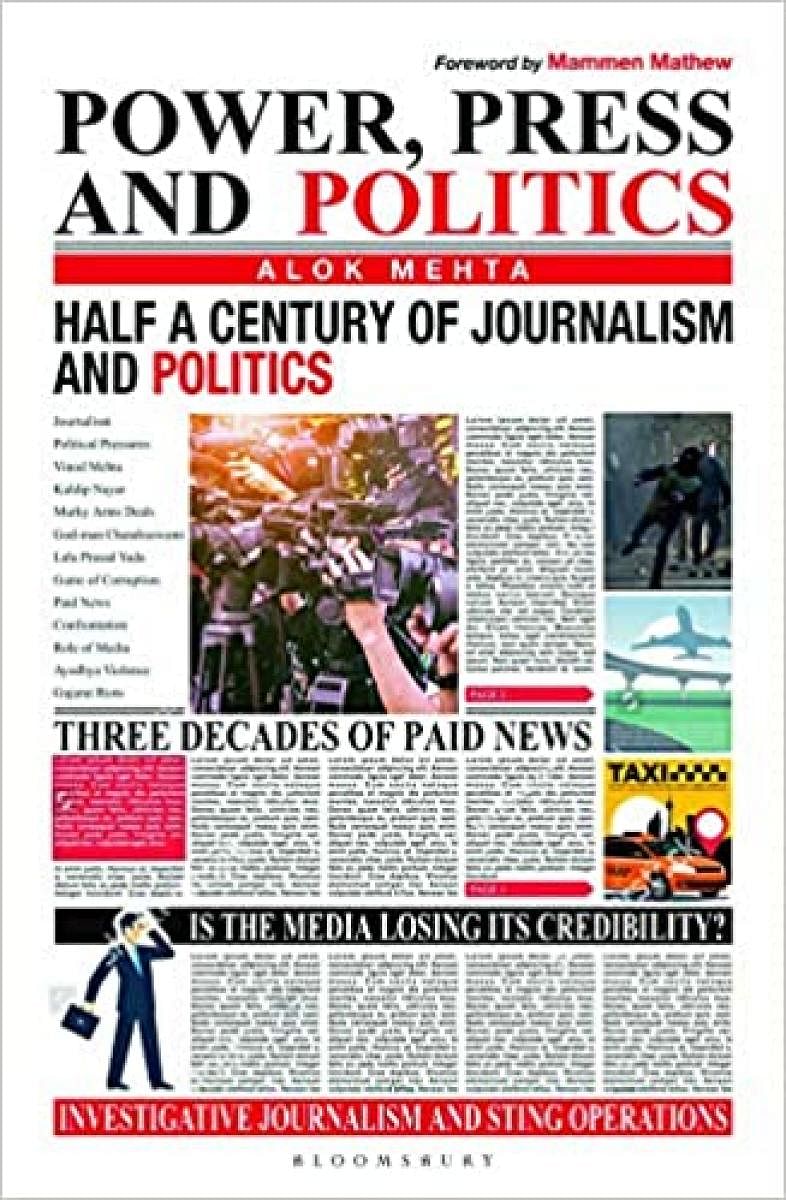

Alok Mehta’s Power, Press and Politics gives a wide-angled view of journalism in the country through the past half a century. It is an insider’s account and is direct reporting from news rooms, offices of editors and proprietors and from corridors and back rooms. That provides his narratives a personal dimension and a historical context.

Journalism is called the first draft of history and Mehta’s book gives accounts of a few media events, describes the players associated with them and goes into the reasons or motives behind them. He has worked in major Hindi newspapers and publications like Nai Dunia, Navbharat Times, Dainik Bhaskar, Hindustan and Outlook Hindi and has over 50 years of journalistic experience. He has also held positions in the Editors’ Guild of India and the Press Council. Much of the book is about the print media with which Mehta is most familiar. Mehta thought it necessary to give a glimpse of the ‘’darkness, claws, hardships and hazards lying behind the glittering positions’’ of editors, and that was the driving idea behind the book.

An important theme that runs through the book is the interaction between power and the press, and power is political power, expressed in various ways, or management power. He has seen from close quarters how journalists and editors work under pressure, not just the time pressure that the profession always lives with, but pressure from politicians, businessmen, owners of their publications and other entities. He has high regard for editors like Rajendra Mathur, Manohar Shyam Joshi and Vinod Mehta, with whom he worked. He remembers their excellent editorial and professional qualities that helped them to cope with challenges and adversities. The book abounds in anecdotes about editors, newspaper owners, politicians and others. Those who give stories to their readers every morning have many stories about themselves, and many of them are interesting. That is not just because they are human interest stories, but also because they help in understanding many events of recent history, especially relating to politics.

The various forms of media and journalism as such changed a lot during the 50 years under Mehta’s gaze. Investigative journalism started getting more attention in the 1970s and 80s, and some of the best journalistic achievements of those times came out of efforts to dig out stories and uncover truths, which would otherwise have remained hidden. Naturally, what was mostly uncovered were stories of corruption and misconduct, and they were pointers to the deteriorating standards of public life and society. Mehta discusses some of them and describes how he himself broke some stories, like those on godman Chandraswami and the fodder scam. He has also touched upon sting operations, which evolved from investigative journalism.

Paid journalism

The challenges faced by journalism engage a lot of Mehta’s attention. These have changed over time but the essential features have remained more or less the same. Apart from political and governmental pressures that work on editors and reporters, there are institutionalised constraints and restrictions which stop a story from being told. Mehta gives details about press censorship during the Emergency, which was an open attack on press freedom by the State. He writes about how it was received by the press. Most accepted it, but some resisted, paying a price for trying to keep the freedom flag flying. He remembers that the then I&B minister VC Shukla’s officers behaved as if they owned the country and treated journalists like vassals.

Another challenge is the entry of industry and business, with their big capital, into the world of media with the intention of influencing government decisions and public opinion. Conversely, media owners entered into other businesses and took advantage of their power to promote these businesses. One new phenomenon that undermines journalism is paid journalism in which politicians or others commission reports by paying money to reporters or even newspaper managements.

The line between editorial and advertisement is blurred and news becomes commerce. it is a violation of the contract with the reader who is unaware of the hidden deal and takes the report in good faith. Mehta describes it in great detail, with examples cited from Press Council reports.

Coloured views?

The book has interesting and informative discussions on the role of bodies like Editors’ Guild and their functioning and the relations between the media and the judiciary. Some reports like a 1992 Press Council report on violence against journalists in Ayodhya and an Editors’ Guild report on impediments to media coverage during the 2002 Gujarat riots are included as annexures in the book. The book would be of interest to journalists, students of the media and others who want to study the interaction between media and politics in the last 50 years. But one difficulty with such writing is that we are not sure if all the inside information is correct, or is coloured by the writer’s views.

Mehta writes mostly about Hindi and English journalism and editors who wrote in those languages. Journalism in regional languages do not get much attention, though there are some references.

The book might have gained from better editing and organisation. There are many errors of spelling, grammar and diction, including annoying mistakes in the captions of photographs. The quality of writing is uneven, and some chapters are better written than others. With all the information and experience that he has at his behest, the author could perhaps have written a better book if he had taken more pains.