It was in the year 1883 that 31-year old artist Leonid Pasternak first met Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, who was by then an international celebrity. His long novels, War and Peace (1869) and Anna Karenina (1878), had made him a household name.

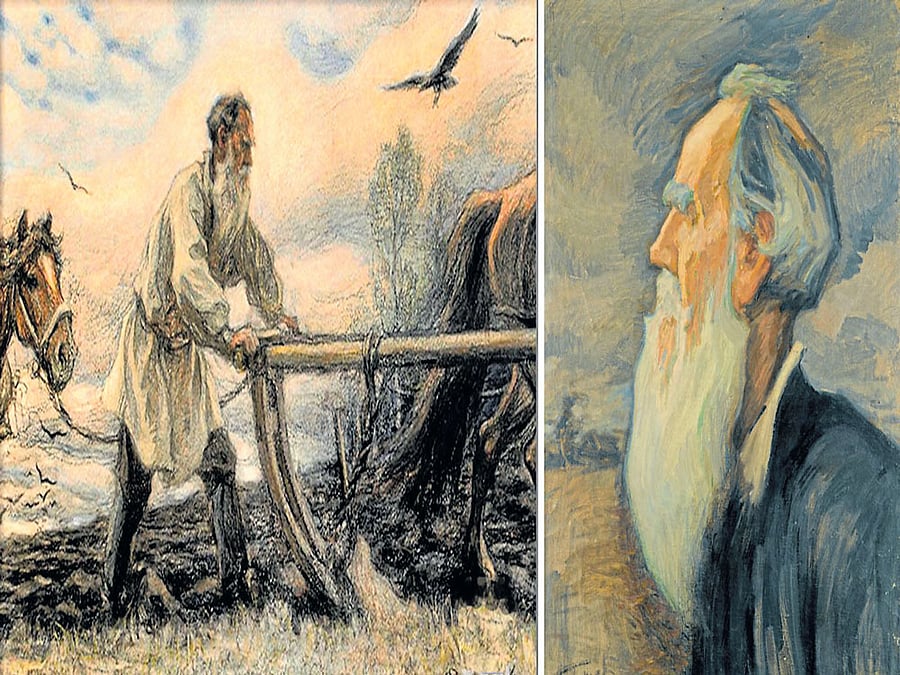

Paradoxically, the enormous success of his writing, and rapidly growing wealth on account of the royalties, had driven the Russian master to depression, midlife crisis, and religious disenchantment. Tormented by inner conflict, existential despair and philosophical questions about the meaning of life in the face of death, Tolstoy had, by the 1880s, become ‘a white-bearded patriarch in peasant’s clothing living among the poor.’

When the 55-year-old novelist visited the 21st Wanderers’ exhibition in Moscow, Pasternak was understandably excited. “Tolstoy suddenly began to look hard at the pictures, as if he were drilling a hole in the air,” he recalled in his memoirs. “I saw the flash and the flare of lightning. I saw a thunderstorm with muffled peals of thunder rumbling behind the storm-clouds. This was the Tolstoy whom I later tried to depict in my profile portrait against the stormy sky.”

A warm friendship quickly sprang between the two from the meeting. Full of admiration for Pasternak’s illustrations, Tolstoy frequently invited him to his Moscow and country residences. He became Pasternak’s frequent model and was depicted in a variety of settings and media.

In the late 1890s, when Tolstoy’s third long novel Resurrection was serialised in a journal, Pasternak sketched and illustrated it with unbridled interest and enthusiasm. His ability to capture the novel’s moods and characters delighted the author.

Pasternak and his wife Rozaliya, an accomplished pianist, were deeply influenced by Tolstoy’s personality, moral idealism and integrity as man and artist. Decades later, Leonid’s son, Boris Pasternak (who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1958), would write about his parents’ reverence towards Tolstoy; and how the whole house was imbued with Tolstoyan spirit.

Lydia, Leonid’s daughter, too, had similar recollection. “The time was characterised by a ‘spiritual atmosphere’ and a ‘Tolstoyan element’ combined with the experience of music.” When Tolstoy died in a little country railway station in November 1910, Leonid and Boris Pasternak hurried there to pay their last respects. Leonid, in fact, made the last drawing of Tolstoy on his deathbed.

Leonid’s monograph on Leo Tolstoy containing paintings and essays was published in Berlin in 1932. Most of the copies were sadly destroyed in 1933, when the Nazis took pride in publicly burning books.

Lightning draughtsmanship

Leonid Pasternak, the youngest of a large family of nine children, loved sketching from an early age. However, his financially struggling parents discouraged his early forays into art; they did not hesitate to even destroy some of his early pictures. Later, while pursuing his legal studies, Leonid continued to chase art by living frugally.

His first major sale of a painting took place in 1888 when ‘Letter from Home’ (30 x 40 cm /pencil on paper /1888) was purchased by art collector Pavel Tretyakov for 2000 roubles. When his second major picture, ‘The Blind Children’s Prayer’, was rejected by a jury in 1890, Leonid along with his younger Moscow colleagues founded a progressive artists’ collective: ‘Group of Thirty-Six artists’. His finances began looking up only in the early 1890s as he gained recognition as a talented illustrator and portraitist. In 1894, he joined the staff of the Moscow School of Painting where he remained for more than 25 years.

Leonid, who had seen life at the lower end of the social ladder in his youth, worked in his studio and home relentlessly producing evocative sketches, watercolours, charcoals and oil paintings. His art was characterised by his lightning draughtsmanship and impressionist painting technique. A true family person, he often sketched his near and dear ones, capturing their characteristic moods and manners.

Leonid’s children saw him as a man of ‘unquestionable loyalty and integrity, with an exaggerated sense of responsibility and duty which made his personal life more austere and difficult than it need have been.’

According to Lydia, he was “a man of dreamy, gentle disposition, kind and altruistic, slow and uncertain in anything but his work, modest, retiring, and with a genuine dislike of being in the limelight, which at times was not easy for him to avoid. He also had a wonderful sense of humour, and an ability for impersonation; observing and drawing were for him a natural necessity, like sleeping and breathing…it was fascinating to watch him at work; when painting a portrait… the speed, the ease and decisiveness with which he worked were truly amazing, and in direct contrast with his usual bearing.”

Politically, Leonid was known to take a moderate position infected by a ‘spirit of revolution’, although in 1905, he had in a letter to his friend expressed horror at the number of victims already claimed by the Revolution. In 1917, he was called to the Kremlin to paint a group portrait of leading Bolsheviks including Lenin and Trotsky. The painting was bought by the state but destroyed in the 1930s because too many of the leaders it portrayed had since been declared ‘enemies of the people’.

Pasternak was forced to flee to Germany with his wife and their two daughters, Lydia and Josephine, from Stalin’s Russia in 1921. (Boris and his brother Alexander remained in the Soviet Union.) In emigration, Leonid created portraits of Albert Einstein, Rainer Maria Rilke, and John Osborne, among others.

As the Nazis took power in Germany, Leonid and his family considered returning to Russia in 1938. Boris, while wanting them to come back, also tried to dissuade them from coming since he feared danger to their lives if they came. The family moved to Oxford, England in 1938.

Heartbroken after his wife died in 1939, and saddened by rare contact with his sons, Leonid spent the last six years of his life as a semi-recluse at Lydia’s home in Oxford, where he died on May 31, 1945 at the age of 83.