Written in Prakrit and set in 50 BCE, the Kalakacharya Katha recounts the mythical story of the Shvetambara Jain monk Kalaka, whose sister is kidnapped by Gardabhilla, the king of Ujjain. Turned away by local kings and princes, the monk enlists the help of 96 princes of the Saka clan, who cross the Indus River to help him defeat his enemy. Between the 13th and 15th centuries, many illustrated Kalakacharya Katha manuscripts were created. They were a standard addendum to the Kalpa Sutra, a text that explains Jain cosmology and is particularly important to the Shvetambara sect of Jainism.

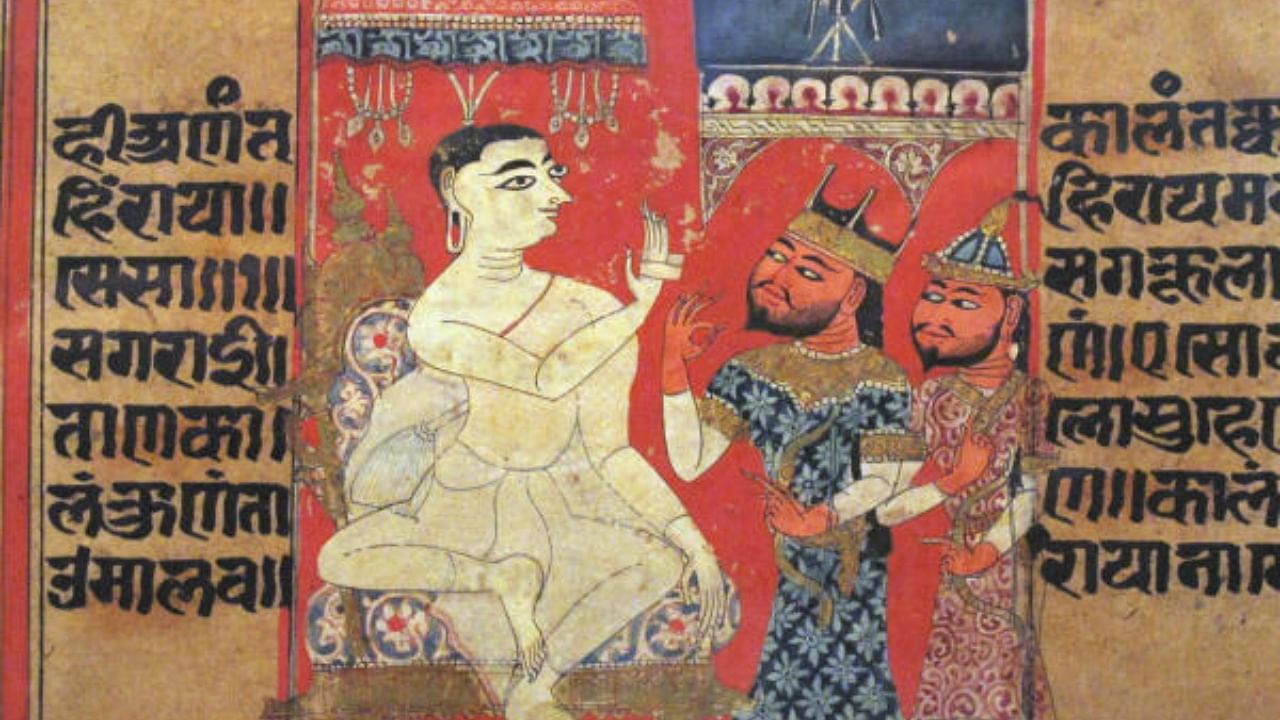

A comparative study of the many illustrated manuscripts reveals a dynamic dialogue between indigenous and Persian influences — both in terms of content and visual language — and is proof of the stylistic maturation of the Western Indian manuscript painting tradition. One illustration from c. 1400 CE shows Gardabhilla being brought before Kalaka by a Saka prince. The latter’s green brocaded attire, headdress, boots, wide cloud collar and trimmed beard are doubtlessly different from the Shvetambara monk’s plain white drape. However, they also contrast Gardhabilla’s garb, although both figures are royalty; the Indian king is shown wearing a block-printed dhoti, an embroidered muslin waist-tie and a differently shaped crown. He also has a Vaishnava tilak on the forehead, a hatched beard and is barefoot. The Saka prince also has a different complexion and a hooked nose and is the only figure with eyes that do not extend beyond his profile. While the red ground of the composition replicates the style of Western Indian paintings from this period, the depiction of the Saka prince, with his eyes set within the three-quarter profile, is distinctly Persian.

This image reveals that the artist had a clear awareness of Persian painting conventions which, by then, had permeated painting ateliers in India. Interactions between the two cultures would continue to develop in the latter half of the fifteenth century. This can be further discerned when one compares a folio from c. 1400 with an illustration from a Kalakacharya Katha manuscript from c. 1475, which shows three monks fording a river. The latter exhibits Persian influences — the use of gold paint instead of black ink in rendering the text, the application of ultramarine blue produced from lapis lazuli stones, which replaces the erstwhile red ground, and the addition of intricate geometric floral patterns to the borders of the folios. Local artists, who now worked for both Muslim sultans and Jain merchants, reinvented their visual language according to the tastes and preferences of their new clients, resulting in the western Indian Jain manuscript tradition acquiring considerable opulence and luxury, borrowing from the ornate and rich Persianate styles. As Jain patronage extended from Gujarat and Rajasthan into Central and Northern India in the late 15th and 16th centuries, artists synthesised indigenous traditions with Persianate styles as well as regional North Indian ateliers, leaving a lasting legacy on the court painting styles of Malwa and other regions.

Discover Indian Art is a monthly column that delves into fascinating stories on art from across the sub-continent, curated by the editors of the MAP Academy. Find them on Instagram as @map_academy