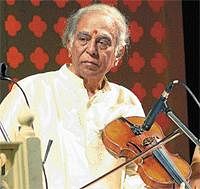

The showpiece of the evening was an instrumental ensemble that performed music composed by his disciple-children Krishnan and Vijayalakshmi, the famous violin duo.

Encomiums were showered by eminent personalities. Documentaries were screened and biographies were read. The celebration was worthy of the celebrity that Lalgudi Maama (as he is known with fond respect in music circles) is.

Mention all this and several other honours bestowed on him, and he is quick to brush it aside. What has given him joy and satisfaction? He says, “Every composition that has come out of me, inspired and unbidden; it is similar to the difficulty and then the delirious joy of childbirth.”

The conversation leads to his formative years as a musician. He asks with childlike curiosity, “Have you seen Lalgudi?”, and then continues, “We used to live at the end of a quiet street. The village itself was green with paddy, sugarcane and other crops and trees. In those days, music concerts did not happen in Lalgudi. Trichy (Tiruchirapalli) hosted all the top performances. I used to board the train at 2 o’clock in the afternoon and reach Trichy at 4 o’clock. Sitting quietly in the audience, I would watch as other listeners excitedly announced the arrival of the artistes. Fiddle Papa (Papa Venkatarama Iyer) has arrived! Palghat Mani (Iyer, the mridangam icon) is here! I used to listen to the concert, stay the night at a relative’s place and reach Lalgudi early next morning.

“I would take up the bow soon after bath and play all that I had heard the previous evening.” Soon, Lalgudi was playing for the stalwarts of the day. After one of his first concerts, one such stalwart, Madurai Mani Iyer, remarked with wonder, “How can you play exactly like I sing!”

This ability to make his violin almost sing like a vocalist perhaps can be traced back to Lalgudi Jayaraman’s initial training as a vocalist. His father Gopala Iyer initially taught him vocal music; but since the boy was frail and there were no microphones then, the father, himself a violinist, introduced the son to the instrument.

Gopala Iyer the disciplinarian then administered music instruction to his son with utmost rigour. Circumstances led to many opportunities as an accompanying violinist; while he took those opportunities, he brought to bear on the instrument his vocal training.

Eventually, it led to a unique baani or style, known widely as the ‘Lalgudi baani.’

After being acknowledged as an adept accompanist, he made his own road not only as a solo performer but as a composer of the highest calibre. In 1965 when he played at the Edinburgh music festival, the internationally renowned violinist Yehudi Menuhin invited him over to his house for breakfast.

Lalgudi recalls with fondness, “After breakfast all three of us (Palghat Mani Iyer was also there) went to the first floor of his house. I had not carried my violin with me. Menuhin handed over his own violin and asked me to play two ragas with contrasting moods. I tuned the violin to suit Carnatic music and then played a joyous Shankarabaranam and a melancholic Shubhapantuvarali. Menuhin was pleased to listen to me. When I said that such technically superior violins were not available in India, Menuhin promised to send me one. Soon after I returned to India, his gift arrived, postage paid. I play it even to this day.”

As a testimony to his growing stature as a composer, his entry was judged the best among 77 others received by the International Music Council and Asia Music Rostrum in 1979.

He composed several unparalleled varnams and thillanas known for their convergence of rhythmic perfection and melodic beauty set to matching lyrics. No wonder then that such compositions have been adopted with relish by dancers and choreographers.

Eminent Bharatanatyam dancer Padma Subrahmanyam notes that by taking up rare ragas in which to compose, Lalgudi added a new dimension to music for classical dance.

His genius for composing music led to many opportunities in filmdom. But he rejected most of them. “The stories did not appeal to me,” he says. “One of them had a sequence in which Kamal Hassan is playing the violin, a cat suddenly appears and he drops the violin to the ground. I could not reconcile myself to that, it didn’t seem proper so I refused.”

However, in 2005 he did compose the music for the movie, Sringaram for which he won the national award for the best music direction.

At 80, the outer frame may have aged but an ever enthusiastic mind still pulsates to the nuances and challenges of Carnatic music. Lalgudi Maama asks, “Have you listened to my latest varnam in Hameer-Kalyani?” We are all ears.