Image one: A man wearing a bright yellow half-sleeve shirt and red trousers, his black hair plastered down, stands with his wife dressed in a bright pink Bandhani sari, her head covered with her pallu. Behind them are small shanties covered with blue plastic sheets. The couple is standing in front of an overflowing gutter. Written in between the shanties is the word Ahmedabad.

Image two: A group of children stand on one side of the road gaping at a school. Nearby, as a man reads a newspaper, women fetch water in plastic buckets while in the background heavy vehicles with painted signs like ‘ICDS gaadi’, ‘Red Cross gaadi’ and ‘sarakari ration truck’ ply.

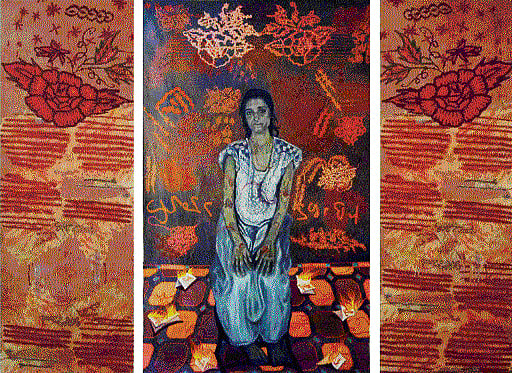

These are artworks created by some very special students of Vasudha Thozhur, 50, a renowned contemporary artist, who deals with the theme of conflict and violence through her paintings. Her innovative art project with six adolescent girls from Faizal Park, Vatwa, in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, who had been caught in the middle of the riots that broke out in the city in 2002, has produced some insightful and poignant creations that not only provide a window into their hearts and minds but have, at one level, had a cathartic effect on them.

It’s been more than a decade since the carnage at Naroda Patiya in Ahmedabad, where residents, including these girls, witnessed unprecedented violence against their close family members, neighbours, friends and acquaintances. Survivors fled with their belongings to settle in a new locality, Faizal Park, Vatwa, on the city’s outskirts. But, instead of dwelling on their loss, they had to learn to get back on their feet.

The works of these youngsters have been showcased in Thozhur’s latest exhibition, Beyond Pain — An Afterlife, which was recently held in Mumbai. Along with her graphic but semi-abstract works in acrylic on large canvasses, which interpreted the massacre and its aftereffects on the victims, there were these paintings that may not bear the finish of professional art but present a slice of life in Vatwa, post-2002, as seen through the eyes of those who had lived through those painful times.

Shahjahan, Tahera, Farzana, Rehana, Tasneem and Rabiya have all lost several members of their immediate family in the carnage and, even though, today, they are grown up women — some married, others working — they all carry the trauma of that period although they don’t talk about it. They were part of the art project, sponsored by the Indian Foundation for the Arts (IFA), Bangalore, and initiated by Thozhur, with the support of Himmat, an organisation set up to work with riot victims.

Until recently, Thozhur was staying in Vadodara, a city around 100 km from the focal point of the 2002 violence. “Although I am not a direct victim, how could anyone remain unaffected by those horrific times? And like several others, soon after the incidents, I too participated in many protest morchas. However, I soon realised that something more needed to be done to help the victims, and being an artist I could think of only art to communicate with them,” she says.

With this in mind, she joined hands with activist-journalist, Bina Srinivasan, and began visiting the affected communities. She held several discussions with many activists working on the issue, but her participation at that point was only as a concerned citizen.

Recalls Monica Wahi, one of the founding members of Himmat, “Vasudha came with Bina, who was associated with us. She had this idea of introducing the drawing and painting to children of Vatwa. As she wanted to pay the girls who came for the workshop a minimum stipend, we decided to seek external funding, though all our activities were previously being funded through our personal contributions.” Himmat assists the new settlers in Vatwa to overcome their trauma.

Initially, it was a difficult task to engage with the riot survivors on art, particularly because they were all barely coping and surviving. While most of the men in their families were dead, those who had escaped were unable to get any jobs. In their new locality they didn’t have access to water — until today they have no water connections. There were also no hospitals, schools or shops closeby. They didn’t even have power connections or sanitation facilities.

Says Thozhur, “We didn’t approach the elders to join the art workshop. Besides doing housework, the older women were busy doing stitching work or any other activity that could ensure an income for them. We spoke to young girls in the age group of 12-18 years. At first, many showed interest but later only six turned up for the workshop.”

The girls were paid Rs 30 per day of work — they didn’t come everyday — and that was one real attraction for them. “I remember one of them told me that she had bought a small cake for her brother’s birthday from the money she had got the previous day. She was so happy and so was her mother! It made me feel so humble and I was convinced that day that through this project, at least, a little can be achieved,’’ says the artist.

That was how the girls were wooed, and those who didn’t even draw a straight line or had never seen any paints, brushes in their life ended up painting beautiful and explanatory works. “They all loved to draw and paint day-to-day incidents rather than their past experiences. I neither asked them the reason for not drawing those events, nor did I talk to them about those difficult days. I don’t think anyone can ever forget the kind of bloodbath these youngsters witnessed. The project wasn’t anyway intended to make them forget their sufferings. It examined the role that art practices can play in a collective trauma and address a range of issues from personal loss to displacement, and the possibility of economic revival through the use of visual language,” she adds.Image one: A man wearing a bright yellow half-sleeve shirt and red trousers, his black hair plastered down, stands with his wife dressed in a bright pink Bandhani sari, her head covered with her pallu. Behind them are small shanties covered with blue plastic sheets. The couple is standing in front of an overflowing gutter. Written in between the shanties is the word Ahmedabad.

Image two: A group of children stand on one side of the road gaping at a school. Nearby, as a man reads a newspaper, women fetch water in plastic buckets while in the background heavy vehicles with painted signs like ‘ICDS gaadi’, ‘Red Cross gaadi’ and ‘sarakari ration truck’ ply.

These are artworks created by some very special students of Vasudha Thozhur, 50, a renowned contemporary artist, who deals with the theme of conflict and violence through her paintings. Her innovative art project with six adolescent girls from Faizal Park, Vatwa, in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, who had been caught in the middle of the riots that broke out in the city in 2002, has produced some insightful and poignant creations that not only provide a window into their hearts and minds but have, at one level, had a cathartic effect on them.

It’s been more than a decade since the carnage at Naroda Patiya in Ahmedabad, where residents, including these girls, witnessed unprecedented violence against their close family members, neighbours, friends and acquaintances. Survivors fled with their belongings to settle in a new locality, Faizal Park, Vatwa, on the city’s outskirts. But, instead of dwelling on their loss, they had to learn to get back on their feet.

The works of these youngsters have been showcased in Thozhur’s latest exhibition, Beyond Pain — An Afterlife, which was recently held in Mumbai. Along with her graphic but semi-abstract works in acrylic on large canvasses, which interpreted the massacre and its aftereffects on the victims, there were these paintings that may not bear the finish of professional art but present a slice of life in Vatwa, post-2002, as seen through the eyes of those who had lived through those painful times.

Shahjahan, Tahera, Farzana, Rehana, Tasneem and Rabiya have all lost several members of their immediate family in the carnage and, even though, today, they are grown up women — some married, others working — they all carry the trauma of that period although they don’t talk about it. They were part of the art project, sponsored by the Indian Foundation for the Arts (IFA), Bangalore, and initiated by Thozhur, with the support of Himmat, an organisation set up to work with riot victims.

Until recently, Thozhur was staying in Vadodara, a city around 100 km from the focal point of the 2002 violence. “Although I am not a direct victim, how could anyone remain unaffected by those horrific times? And like several others, soon after the incidents, I too participated in many protest morchas. However, I soon realised that something more needed to be done to help the victims, and being an artist I could think of only art to communicate with them,” she says.

With this in mind, she joined hands with activist-journalist, Bina Srinivasan, and began visiting the affected communities. She held several discussions with many activists working on the issue, but her participation at that point was only as a concerned citizen.

Recalls Monica Wahi, one of the founding members of Himmat, “Vasudha came with Bina, who was associated with us. She had this idea of introducing the drawing and painting to children of Vatwa. As she wanted to pay the girls who came for the workshop a minimum stipend, we decided to seek external funding, though all our activities were previously being funded through our personal contributions.” Himmat assists the new settlers in Vatwa to overcome their trauma.

Initially, it was a difficult task to engage with the riot survivors on art, particularly because they were all barely coping and surviving. While most of the men in their families were dead, those who had escaped were unable to get any jobs. In their new locality they didn’t have access to water — until today they have no water connections. There were also no hospitals, schools or shops closeby. They didn’t even have power connections or sanitation facilities.

Says Thozhur, “We didn’t approach the elders to join the art workshop. Besides doing housework, the older women were busy doing stitching work or any other activity that could ensure an income for them. We spoke to young girls in the age group of 12-18 years. At first, many showed interest but later only six turned up for the workshop.”

The girls were paid Rs 30 per day of work — they didn’t come everyday — and that was one real attraction for them. “I remember one of them told me that she had bought a small cake for her brother’s birthday from the money she had got the previous day. She was so happy and so was her mother! It made me feel so humble and I was convinced that day that through this project, at least, a little can be achieved,’’ says the artist.

That was how the girls were wooed, and those who didn’t even draw a straight line or had never seen any paints, brushes in their life ended up painting beautiful and explanatory works. “They all loved to draw and paint day-to-day incidents rather than their past experiences. I neither asked them the reason for not drawing those events, nor did I talk to them about those difficult days. I don’t think anyone can ever forget the kind of bloodbath these youngsters witnessed. The project wasn’t anyway intended to make them forget their sufferings. It examined the role that art practices can play in a collective trauma and address a range of issues from personal loss to displacement, and the possibility of economic revival through the use of visual language,” she adds.

Surekha Kadapa-Bose

Women’s Feature Service