Bharti Kirchner’s Goddess of Fire is a fitting title for the story of a woman who escapes her fate as a sati, and goes on to reinvent herself as the power to be reckoned with, in the echelons of East India Company.

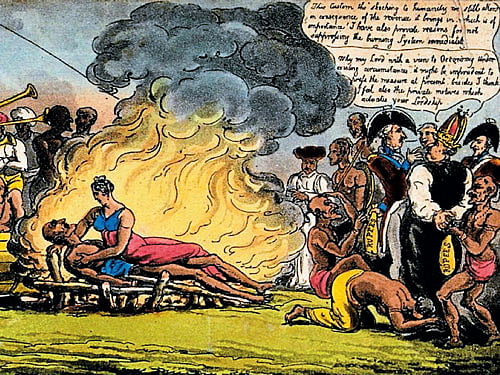

Based on the true historical figures of Job Charnock and his wife, this novel is seen through the eyes of his Hindu common-law wife. Job, a trader in East India Company, sees a pretty, young and a rather unwilling widow on her funeral pyre and rescues her. He brings her to Cossimbazaar, changes her name from Moorthi to Maria, and employs her as a cook in the Company. In the kitchen, the 17-year-old quickly befriends her co-workers and gleans important information about the sahibs, their hierarchy, and the Company. Not content to be a lowly cook, she aspires to be an interpreter and takes lessons in English.

Through shrewd trading tactics she wins the attention of the Council and rises to the position of a Factor in the Company. Fuelling her ambition is her deep love for Job Charnock. Misfortune, however, follows close on Maria’s heels. Just as she has repulsed the unwanted attentions of a sahib, news reaches her that her husband’s family is in town to ask for the Nawab’s help in punishing Job for his audacity in spiriting their sati away. Maria appears at the Nawab’s court, speaks out against the practice of sati, and successfully petitions for Job’s pardon for his role in rescuing her. Next, the opportunity to act as an interpreter comes unbeckoned, when Maria is pressed into service to negotiate with a neighbouring Rani. On their way there, they are suddenly confronted by the Nawab’s soldiers and it is Maria’s cool lying that saves their skins. Little by little, Maria makes herself indispensable to the sahibs. Job, who is not immune to her charms, now slowly admits it to himself.

The imposition of a customs duty breaks in on Job’s and Maria’s new-found happiness. Job incurs the Nawab’s wrath by refusing to pay the tariff as it is a breach of the original firman. His hope of reinforcement forces from England to support him do not arrive.

Instead, the Company advises Job to sign a peace treaty with the Nawab. Job, however, is determined to have it out, and Maria is forced to flee with her unborn baby. The skirmish with the Nawab’s forces leaves Job a man broken in body and spirit. Maria struggles through this crisis, managing both her family and Company responsibilities. As it must, their love also goes through a final touchstone test. The Company decides to build a “white only” town that earns Job’s approval but Maria’s anger. Their love shows up its weak spot. Both Job and Maria feel the pull of their origins strongly and must part ways. Finally, it’s Job’s sickness that brings Maria back to him and her vision of a land where the whites and natives live together and profit from each other.

Based loosely on the historical times and events of Bengal in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Kirchner admits that she has taken the historical figures of Job and Maria and fleshed them out. Kirchner’s Maria is a poor Brahmin girl who narrowly escapes death, starts as a kitchen maid, and fights her way to the top to sit with the English, demanding equal respect and rights. She is loyal to the Company as well as protective of the interests of her people. She is simply too good to be true.

There is no gradual build up to a sauve Maria, shrewd to the ways of the world, from an innocent one. There are no agonies, there is no soul-searching, no dithering. She simply marches like a stiff soldier towards her goal. There are real slips too. A poor Brahmin girl “repulsed by the smell of cow dung” is as likely as a cow jumping over the moon. As an unexposed girl from a village, her easy familiarity with Job is jarring. Even if we make allowances for her sharp, native intelligence, where did she learn her self-confidence, her complete unselfconsciousness as a woman, that too a native woman among English men at that? Job’s character is just as flat. He is a principled man with a penchant for dressing up in opulent desi clothes. If there’s an inner turmoil, it is safely hidden from us. His rush to compliment Maria on her cooking and apologise for the uncouth behaviour of his guests towards her, rings false. The scene where Maria attacks gun-toting Charles (Job’s rebellious colleague) with her broom to protect her beloved Job, has touches of Bollywood. Historical incidents are in place, but compelling characterisation is missing. A novel for light reading.