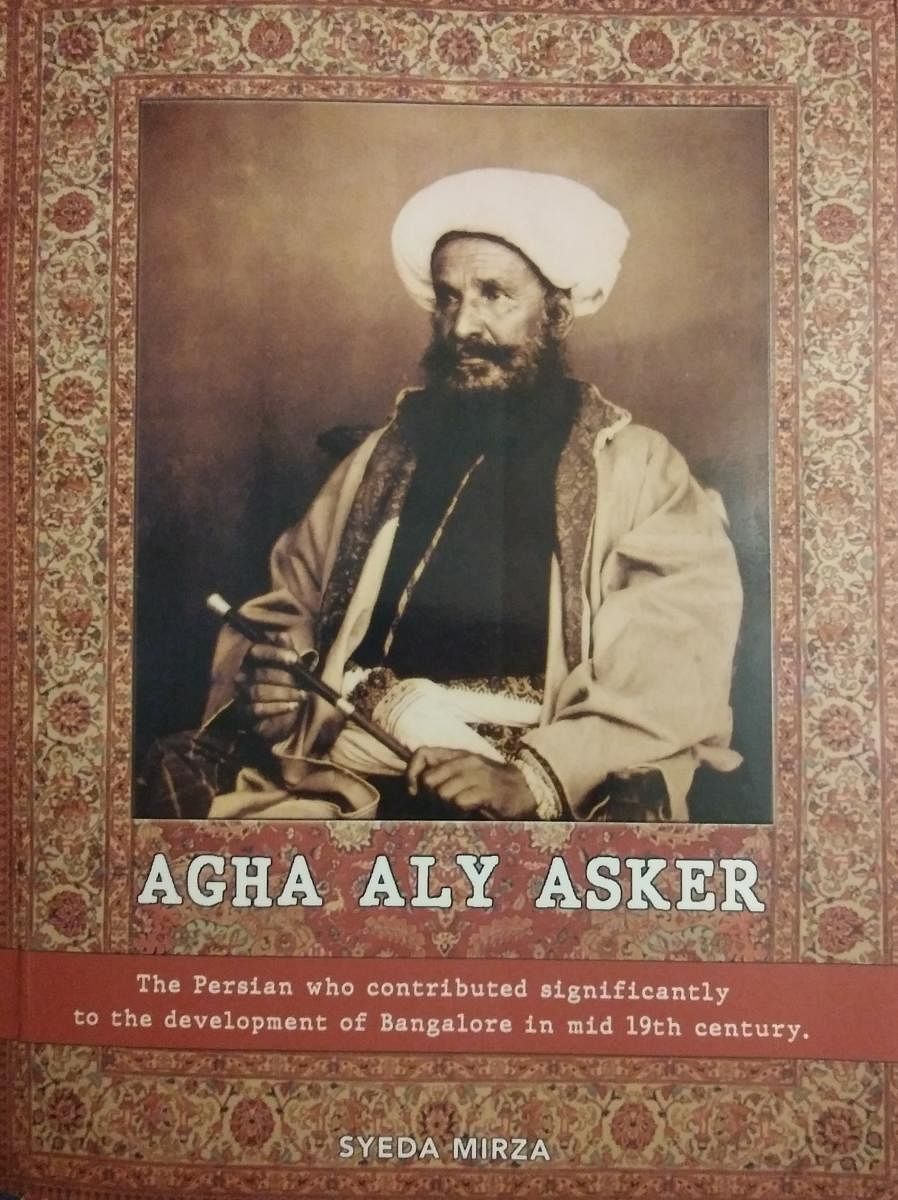

In the early 1800s, a 16-year-old boy left the comforts of his home in Iran and moved to Bengaluru to sell horses. In her new book ‘Agha Aly Asker’, Syeda Mirza tells the scintillating tale of this young lad who ended up leaving behind a rich, tangible and diverse legacy that includes a tradition of horse-racing, several colonial buildings, a mosque, and illustrious descendants who are inextricably entwined with the story of the city, his grandson Sir Mirza Ismail among them.

Syeda Mirza tells his story with love and archival research. Being married into the family — her husband is a great-grandson of Aly Asker’s — she had always heard stories about the man but the trigger to write it all down came around 18 years ago. “They wanted to rename Ali Asker Road in Bengaluru after a minister who lived there,” says Mirza. “Agha Aly Asker was so much a part of the history here, we thought, how could they do that? But though so much has been written about his grandson, Sir Mirza Ismail, nobody knew about Aly Asker. That’s when I started to write.” Aly Asker was the pioneer of the family, Mirza says. “It was because of him that Sir Mirza was able to be where he was. It was so daring of him to come away at the age of 16. I thought the grandchildren should know about this ancestor who came here.” But what started as a simple story to tell her grandchildren grew into something bigger. “It was Bengaluru’s history. And everyone said I had to write it for a wider audience.”

From Shiraz to Cantonment

The story begins when Aly Asker and his two brothers heard in the chai khanehs or teahouses of Shiraz about the huge demand for horses in India. That prompted the brothers to plunge into the trade in horses. As they were getting their travel documents examined, they heard this advice from some British officials: “Go to Bengaluru. There is a new cantonment and the British there need horses.” And so the die was cast.

Aly Asker arrived in Bengaluru in 1824 and he thrived. His business led to close friendships with men interested in horses, racing and riding, or in other words, the who’s who in Bengaluru and Mysore. “He and the Maharaja (Krishnaraja Wodeyar III) were friends, they met as equals,” says Mirza. Another friend and mentor was Sir Mark Cubbon. In fact, Mirza says, Aly Asker’s first wife was recommended to him by Cubbon.

Asker’s interest in horses was instrumental in putting Bengaluru on the racing map. Apart from horses, Aly Asker’s other business was houses. The story goes that when accommodation was needed for the cantonment’s burgeoning British establishment, Cubbon commissioned Aly Asker to build a hundred houses, which he did. “There might have been more but we don’t know. There were also bungalows for the family,” Mirza adds. Old Bengalureans may remember some of these lost bungalows, which added such charm to the city. There was a string of them on Palace Road near High Point, and on Sankey Road, Cunningham Road and Richmond Road. ‘Fairfield’ where Mirza lived is now a layout. ‘Behesht’ on Ali Asker Road was demolished.

A part of Aly Asker’s family home near Johnson Market still stands. The mosque nearby, Bengaluru’s first and for long, the only Shia mosque, was built thanks to a bequest in his will. The book is peppered with other nuggets of city history, and of course, anecdotes about Aly Asker. Through them, we see how a warm, loyal, principled and hard-working man became woven into Bengaluru’s fabric. “That was India. People from everywhere came and were welcomed. They became a part of the culture,” says Mirza. “But now, some people are trying to make it different,” she rues.