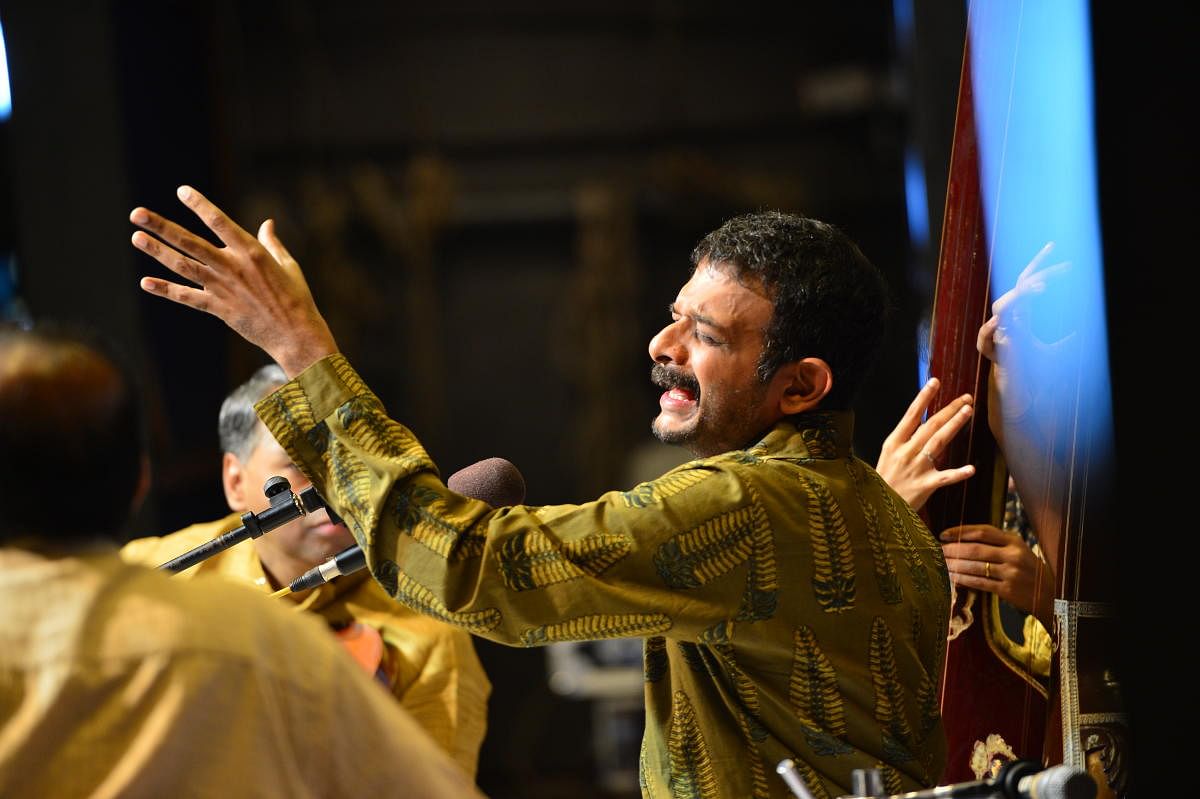

The temptation to slot T M Krishna is huge. He plays so many roles that it is indeed a tough task to resist bracketing him. A performing artiste, a writer, a cultural activist and a social worker for some; a dissenter, a contrarian and a rebellious non-conformist for others.

Even those who fume that he “hogs the limelight” for one reason or the other cannot deny the fact that he strikes a chord — no matter which role he plays. Is it because he, in the process, becomes the voice of the voiceless? Or perhaps because he does not mind calling out his own privileges? It is another matter that he has an obvious advantage of the gift of the gab, which he employs ruthlessly to question people and challenge the many ingrained biases in the world that surrounds him. Prod him if that presents a danger of people forgetting his primary identity as a Carnatic singer, he comes up with an unusual take on it.

“Multiple people view me in multiple ways and that’s their right. I personally have not separated my activism or writing from my music. I only see them as being continuations of each other. Some people may refuse to listen to my music anymore because they consider my activism wrong and there are people who got to know me as an activist first and only later as an artiste. I don’t have any control over that and I don’t think any of it should be a reason why I should not do what I strongly believe in. If I’m going to lose rasikas because of that, so be it,” he replies.

So what initially spurred a young T M Krishna to challenge the status quo? It’s worthy to remember that he had once subscribed to the view that Carnatic music was a superior art form that only a few can perform (before he shunned this opinion, of course). “These conversations weren’t there in the world of Carnatic music or at my home at all. My world view changed when I started looking at the history of the art form and began reading up more. That’s when these questions started emerging — of what you consider superior and inferior and if they are emblematic of your social makeup than the art itself. It was also a way of self-critiquing. There’s no end to it — you’re learning constantly.”

Music integral

From calling out the classical fraternity’s deafening silence during the #MeToo movement to his response to the threats to musicians for supposedly singing Christian hymns and his idea of the national anthem as a protest song in the wake of anti-CAA protests, music has been integral to his idea of activism. Even when the classical fraternity took some (late) initiatives to come together in that hour of uncertainty, he was quick to remind them that such efforts would be a farce until issues of #MeToo and caste discrimination in art practices are not discussed openly. “What makes this worse is the inclusion of those accused of misdemeanour and sexual harassment in a group that’s supposedly helping artistes. Covering up your ugliness by so-called acts of help and brushing things under your carpet is worse than doing nothing,” he says, not one to ever mince words.

Telling other people’s stories

His recent book, Sebastian and Sons, where he traces the origins of the mridangam and its makers and the underlying casteism within the classical fraternity, has been a constant feature of many online conversations over the past few months. Barring the initial controversy surrounding its launch, the reviews for the book, where he talked to over 43 mridangam makers and 10 mridangam artistes, have been overwhelmingly positive. “Every author would want his/her book to raise questions and be the talking point in debates and conversations. I am glad that readers have realised that the book is as much about the Indian society as about the music makers. There were a few disagreements with the book and some responses were even combative, but this is still very rewarding for an author.”

The writing in Sebastian and Sons introduces us to the storyteller in T M Krishna like never before. It’s a non-fictional work written with a novelist’s touch. It makes for a riveting read with the musician’s earnestness to absorb the stories of his subjects and his ability to look at the larger picture shining through. He concurs his approach was unique: “This book was very different writing for me; it was a new form for someone who has largely explored philosophical ideations driven by research (treatises), activism and self-introspection. This is the first time I wrote a book with the approach of a journalist. And it was other people’s stories, which I was trying to make sense of. I completely enjoyed the role of being an observer and a commentator.”

He found the fieldwork so invigorating that he didn’t know when to put an end to his research. “Given a chance, the interviews would have gone on for three more years. There’s a point where I had to tell myself to stop and get to the writing. Fieldwork is the most invigorating part of this process and it is intellectually, psychologically and emotionally challenging. I was understanding new things about myself, the society, history and found it a great way to relook at the world of art and culture. I spent a lot of time with the material even though the book wasn’t being written yet. I didn’t know how to put the book together, because there was so much material (nearly 4,000 minutes of recordings). It took me almost eight months of listening and thinking about all that I had collected and how the stories could be told,” he said, recalling his writing process.

A lost opportunity?

It’s hard to ignore the mention of Rajiv Menon’s film Sarvam Thaala Mayam in the book, during its attempt to discuss the equation between the mridangam maker and the artiste. The rare cinematic attempt to discuss caste and instrument-makers in the classical world was inspired by the real-life instance of a mridangam maker son’s tutelage under the legend Umayalpuram Sivaraman. TMK though, sees this film as a lost opportunity to discuss a larger issue. “The guy (the protagonist in the film) is keener on the transformation within himself; he doesn’t question the teacher and finally finds out that the only way to socially raise himself is to be a mridangam player. Where is the mridangam maker by the end of the film? (suggesting that there’s no change in his social status)... it’s like making a film on women minus feminist combativeness in the dialogues.”

Many have come to him asking if the book would change the life of the mridangam maker after all, but T M Krishna remains hopeful. “At least, the cultural change of calling them instrument makers and not repairers (as it was done in the past) is welcoming. I hope the book results in meaningful relationships between the instrumentalist and the instrument-maker. I’m very positive that the next generation is thinking about these things. I’d be happy if this results in a socio-economic change in the life of the maker.”

Lockdown conversations

Though T M Krishna may have found it difficult to restrict himself amid four walls during the lockdown, he’s hardly been the one to complain about it and even admits that he’s in a relatively comfortable space, economically and socially, to handle this phase. Over the past three months, he has been standing up for those who’re on the margins to the best of his abilities through collectives and his foundation (Sumanasa). Supporting over 20,000 migrant workers in Tamil Nadu, raising funds for over 1,300 folk artistes while also working with the homeless, his new normal has also been about online discussions, talks and an occasional virtual concert.

Another significant idea that sprung from the lockdown as well as the musician’s book writing process was his online series, The Artiste, featuring his conversations with performers Deepan, Kannan and Vyasarpadi Kothandaraman, their tryst with instruments like the parai and the nadaswaram and the many stories that complete their world. “We were thinking of doing something on the YouTube channel and I was not comfortable just releasing their videos. The fact that I was writing this book made me think about the conversations we should have. I hope we can continue the series after the lockdown ends as well,” he adds.

'I see no problem in what Kamal has said'

When TMK was asked to express his opinion about the recent Tyagaraja controversy that Kamal Hassan got himself into, this is what he had to say:

"It's in the context of an art film and a commercial film that Kamal Haasan uses the analogy of Tyagaraja. He clearly is referring to someone who practices art without any interest in its commercial aspect. When he says pichai, he means a person who does not expect anything in return to what he does. All that mattered to Tyagaraja was singing about Lord Rama and he went to every house and took alms. I see no problem in what Kamal has said. The fact that people were affected by this one word pichai only reveals their thought process and inherently casteist nature. They are the ones who associate pichai with only a certain kind of people who wear torn clothes and don't belong to the same caste as them. If he had said biksha, nobody would have complained. If anything, people who signed those petitions (demanding Kamal Haasan's apology) have only further revealed what's wrong with the Carnatic world. I would also ask people to read history, comprehend the political and social times of Tyagaraja, how his financial position was, etc., and do their research before commenting on such things."