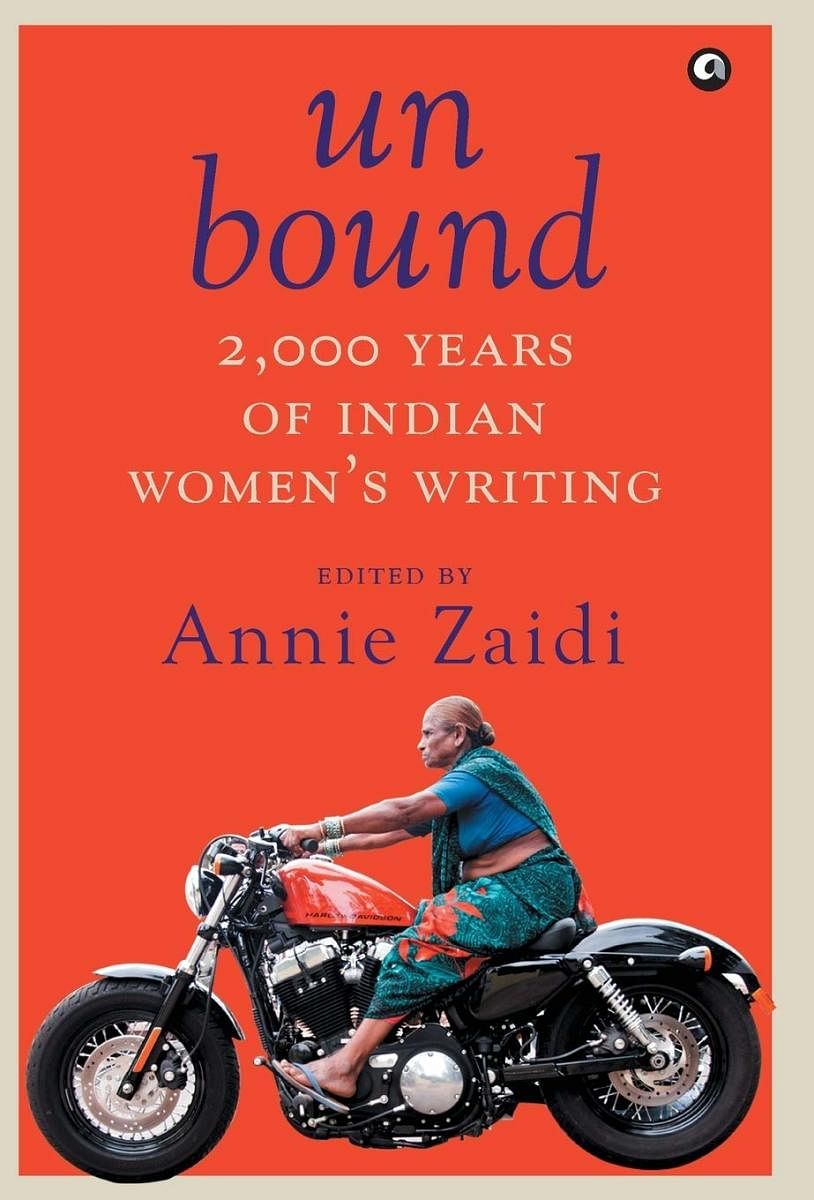

I have to be honest. I’ve really been struggling to read, of late. Much of it is because, as an editor, I work with words all day long, as a result of which I’m often tired of them. Which is why, I initially turned to ‘Unbound: 2,000 Years of Indian Women’s Writing’, perfect to dip into when you need something to anchor you, but you don’t want to commit to anything long-term.

As I read it though, it struck me how incredible this collection really is — that in around 300 pages, you get to briefly inhabit the lives of so many women, living in different realities, and across time. Published by Aleph, the collection ranges from verses written by Buddhist nuns (circa 300 BCE) and poet-saints like Andaal, to contemporary writers like Salma and Urvashi Butalia.

Reading diverse women, you’re likely to see certain themes emerge over and over again, like the relentless demands of caregiving, and how we’re raised to put others’ needs before our own: parents, spouses, spouses’ parents, and children. I did find it infuriating, considering how women’s freedoms continue to be curbed, but a bit of anger is not a bad thing. As the editor of the anthology, Annie Zaidi’s strength lies in being able to capture these multiple truths, while also highlighting how women have always bent and defied these rules with courage and sharpness.

One of my favourite excerpts is from Ismat Chughtai’s ‘In the Name of those Married Women’. When the author gets into trouble for one of her stories and is summoned to Lahore on charges of obscenity, she is unafraid. “I’ve got a great desire to see a prison house,” she jokes, asking the inspector if he’s brought handcuffs. And when she finally appears in court, she’s disappointed that it turns out to be without drama. That same evening, she wanders through Lahore with her husband Shahid and writer Manto to buy Kashmiri shawls and shoes. There’s something so powerful about her utter fearlessness, and sense of adventure.

What women write about

The way the sections are organised — from spiritual and secular love, to work and battles —also reveal so much about women’s priorities and interests at certain periods in history. You get a real sense of what they chose to write about, and what was deemed acceptable. Zaidi does a fantastic job of introducing each section and bringing in her own point of view. For instance, in the section on marriage, which could easily have been romanticised, she points out that it is after all an institution that doesn’t favour women who live outside of it.

Reading a bit from Kamala Das’ ‘My Story’, in which she’s chided for taking time to be away from her child and domestic responsibilities, I had to remind myself that while I’ve made the choice to not have a child, I’m constantly told that I will likely regret it. After all, what sort of woman turns away from the joys of motherhood?

Zaidi’s selection of writing made me think about the importance of personal histories, and staying connected to the women who came before you, especially given that they weren’t always encouraged to write, and speak their minds. It introduced me to so many writers I wasn’t aware of — Mamta Kalia’s clever poetry astonished me — and the range of themes explored in the collection blew my mind: from seasickness and the remnants of birthing to the linguistic system of the Igbo and the tragic assassination of Gandhi, seen through the eyes of a Naga family. In her foreword, Zaidi writes about the dismissal of ‘domestic’ fiction and challenges the notion of it lacking a sense of imaginative daring. She writes about how reading for this project gave her perspective on the distance Indian women have travelled. At the same time, she shares her conflict: “Must we continue to put ‘women writers’ in a box of their own?”

As someone who grew up in India, ‘Unbound’ stirs up so many buried emotions and makes me think of my own past: getting caught by teachers in school for being ‘over-friendly’ with boys, being scolded by an old man on the bus for the length of my shirt, seemingly polite questions at not having changed my surname after marriage — the list is endless. As the year ends and we all introspect, I’m grateful for editors like Zaidi who have spent time gathering the rich voices of women, knowing it’ll always make readers like me feel less alone.

The author is a Bengaluru-based writer and editor who believes in the power of daily naps. Find her on Instagram @yaminivijayan

Unbound is a monthly column for anyone who likes to take shelter in books, and briefly forget the dreariness of adult life.