Atal Behari Vajpayee was a versatile personality. A poet, journalist, fiery orator, outstanding parliamentarian, and a moderate who went on to become the Prime Minister of India. It is neither easy to understand such a great personality nor appraise him accurately. There have been many attempts in the past but such accounts range from being extremely venerative to highly critical, depending on ideological leanings.

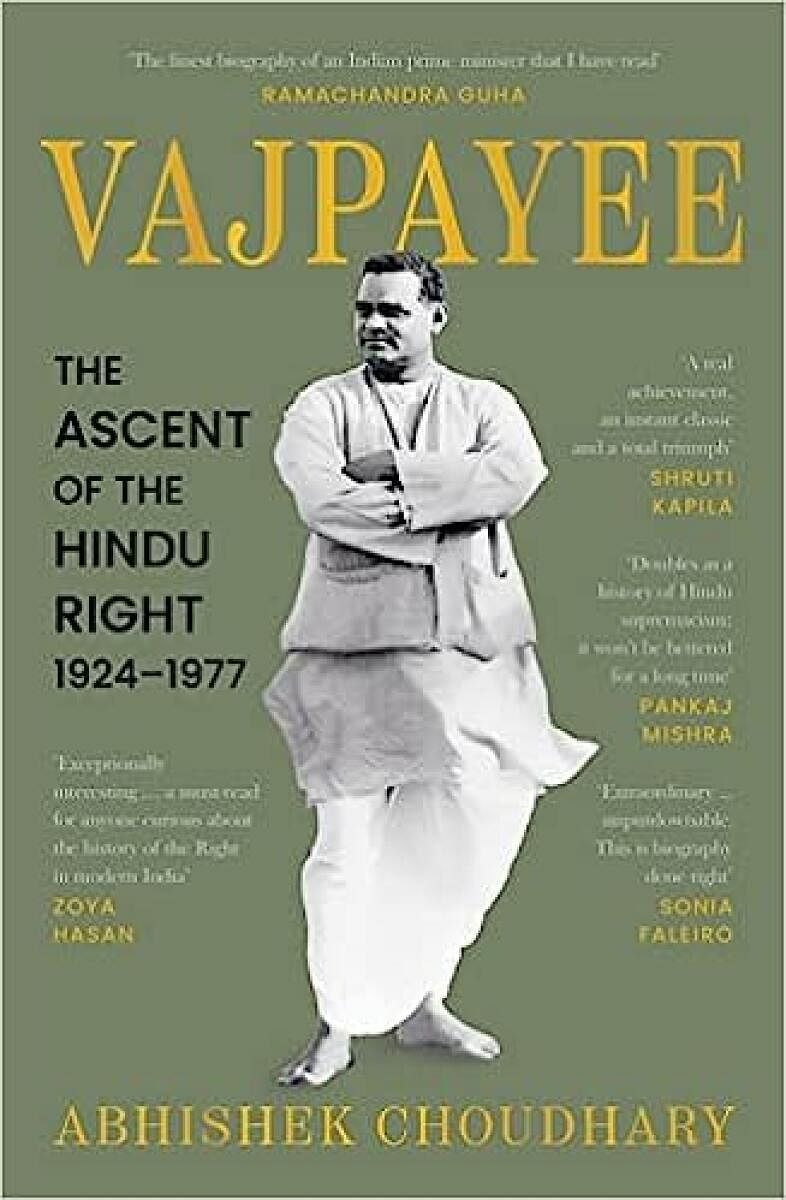

Abhishek Choudhary’s book, the first of a two-volume account, is a compelling read. Based on eight years of painstaking research, the author provides a powerful narrative backed by intellectual rigour. He demolishes several myths surrounding Vajpayee including the one about Vajpayee being an academic prodigy, with concrete proof to the contrary.

The years between 1924-1977 were an eventful and tumultuous period in Indian history. This period also coincided with Vajpayee’s formative years. In his account of these years, Choudhary tries to “locate Vajpayee in the larger pantheon of Hindu nationalism by establishing the timeline and causes of his ascent”.

Atal’s worldview was thus shaped as a reaction to Islamic and British rule. According to the author, his poems spoke of “the intense rage and victimhood Atal felt; that he had come to have a sharp, if also narrow and confused sense of India’s history and geography and the need for its revival and a sense of his own place in the wider world.”

While discussing Atal’s essay of 1947, the author detects the inherent contradiction between the RSS-Mahasabha dreams of Akhand Bharat — a reunited India — on the one hand and calls for driving out Muslims who chose to live in India, on the other.

Deendayal’s protégé, Atal, became the first RSS Swayamsevak to rise up the ranks and enter Lok Sabha at the age of 32. As a Member of Parliament, Atal advocated a firm policy on Kashmir and the abrogation of Article 370. He critiqued Nehru’s China policy when China brutally crushed an uprising in Tibet in 1959 and also critiqued India’s acceptance of Chinese suzerainty over Tibet. He also mocked Nehru’s blind trust in China instead of relying on military preparedness.

Taking a critical stance, the author observes that Atal had little to offer by way of a solution. In his idiosyncratic way, Vajpayee called on Nehru to give a clarion call to ‘drive the Chinese from the land’ suggesting that if such a call were given, the nation ‘will respond unitedly’. The author observes: “The threat of throwing out the enemy by force was the manifestation of a curious Sangh Psychology: that if enough Indians (preferably Hindus, especially RSS-trained) together stood up at the border with lathis, the enemy would run away scared; and that as a last resort, it could even substitute military strategy or peaceful negotiations.”

I think Choudhary underplays the role of collective resistance by a nation united by common feelings against an invader. Also, the author’s too easy and dismissive reference to national security as being a ‘pet peeve’ of Vajpayee under-imagines the prescience of the ex-PM as the events in the past seven decades have shown.

His electoral rival in Balrampur, Ms Subhadra Joshi accused Vajpayee of having cultivated an image of being moderate. Choudhary quotes her as follows: “The thought never crossed any democratic mind that Vajpayee was only acting the liberal to provide cover to the RSS so that [the] fascist machine could gain time it needed to build adequate strength.”

This book has come at the right time. Atal was born on 25 December 1924 and his 100th-anniversary celebrations are likely to start at the end of this year.

The book notes Vajpayee’s fondness for good food, sweets, bhang, and liquor, not to mention his sense of humour and talent for wordplay. The author though never comes across as over-awed by his subject and deserves accolades for his efforts.

The reviewer is the Vice Chancellor of RV University, Bengaluru.