To read Patricia Highsmith is to be drawn into a mire, an amoral soup, a veritable buffet of men behaving badly. White American men for the most part. Death abounds: usually violent murders. And unlike the golden age of detective fiction — the Christies, the Sayers, the Allinghams — in a Highsmith yarn of crime you’re by the killer’s side as the murder is committed. These are not whodunnits by any definition. You know whodunnit — you’re just wondering how (and if) they will get away with it.

Highsmith was born in 1921 in Fort Worth, Texas to a mother who was an artist and a father who was an illustrator. They divorced mere days after her birth and her mother remarried and moved to New York. Highsmith was raised mostly in Greenwich Village and the city was a setting for many of the stories she wrote. Her first novel, Strangers on a Train, was published in 1950 and made into a classic film by Alfred Hitchcock and her literary career was pretty much unstoppable after that.

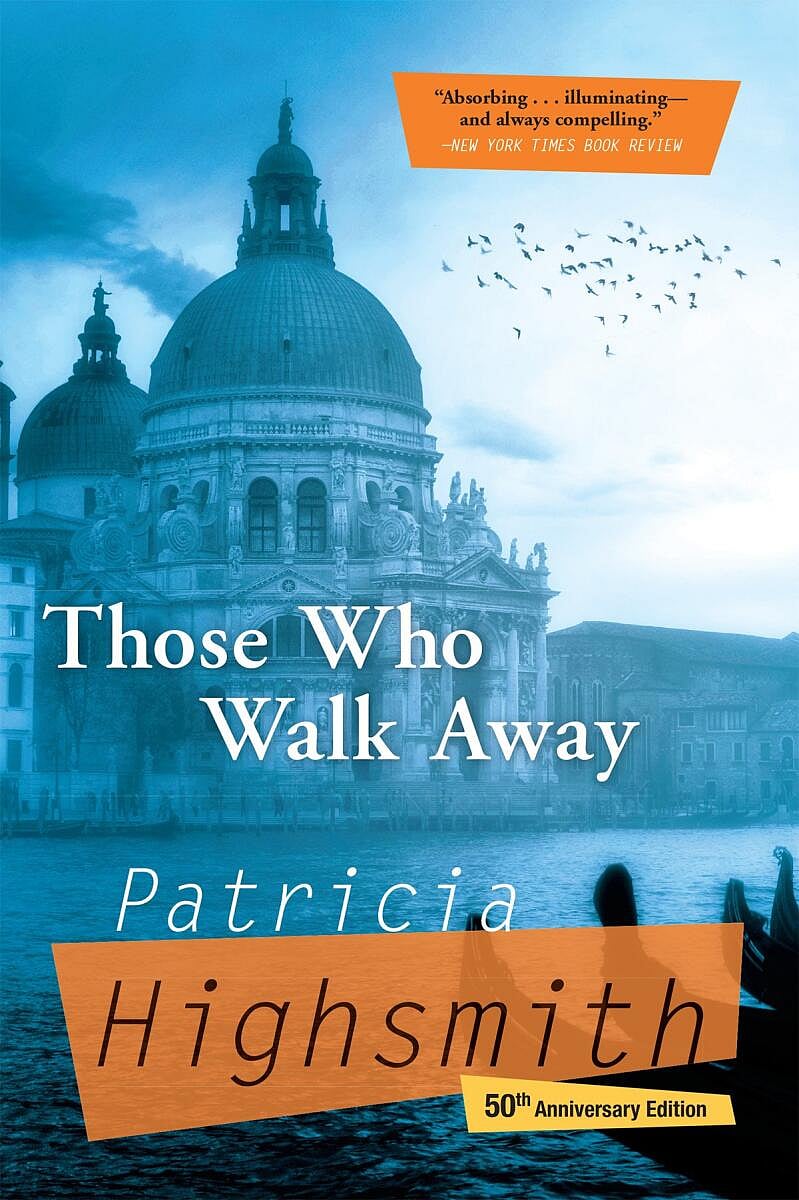

Those Who Walk Away was Highsmith’s twelfth novel, first published in 1967. While the Ripley novels might have made her reputation, it’s in this story, of a father wrestling with anger and murderous antipathy towards his son-in-law that you get Highsmith’s literary craft and moral universe in all its febrile glory.

The story begins in Rome where the aforementioned father, and artist named Edward Coleman, and his son-in-law Ray Garrett walk the streets of the city mourning a common loss. Coleman’s daughter and Garrett’s wife, Peggy, has killed herself a few days before. As they speak, Coleman takes out a gun and shoots Garrett.

While Garrett somehow survives this clumsy murder attempt, Coleman runs off to Venice with his girlfriend Inez. Garrett pursues him there and a cat-and-mouse chase begins around the canals of that city. Coleman doesn’t let up on punishing his son-in-law whom he holds responsible for his daughter’s death. Grief and anger propel his pursuit and the two men wrestle with each other in what seems to be a duel to the death.

The story is told from the viewpoints of both men, switching back and forth as the hunter becomes the hunted. Other writers of noir and murder mysteries would rather give a black-and-white view of the world. But in the universe of Patricia Highsmith, no one has the upper hand in any sense — this isn’t a world where you can expect fairness and justice. When Garrett is swallowing a huge pill to tackle a fever, he remembers “…being ill once in Paris, when he was a child, being given a large pill to swallow and asking the doctor in French, ‘Why is this so big?’ ‘So the nurses won’t drop them,’ the doctor had said as if it were self-evident, and Ray still recalled his shock and sense of injustice that a nurse’s fingers should be thought of before his own throat.”

Highsmith’s great ability is to make us sympathise with even the worst monsters of her creation and while neither of the men in Those Who Walk Away is truly evil, her prodigious skill allows us to care for both in equal measure. There are no villains here — just very flawed, broken human beings.

The author is a writer and communications professional. When she’s not reading, writing or watching cat videos, she can be found on Instagram @saudha_k where she posts about reading, writing, and cats.

That One Book is a fortnightly column that does exactly what it says — it takes up one great classic and tells you why it is (still) great.