No amount of cajoling or cooing would stop the wails. More out of frustration than anything else, I whipped out a colourful children’s book from my bag and held it in front of the child.

Yes, you can guess what happened. For a few minutes there was peace and relief all around as we gazed at the wide-eyed child looking at the book. Could she read? No. But she could see, and that for her, like for most children, was the first step towards making a connection between the printed picture and word.

Pictures in a book are the first introduction for children into the delightful world of books. For many children, it is infatuation at first sight. The look of a book, the feel of the pages, the funny figures on the pages and the letters that they may or may not be able to read, together make a book a joy to hold. This attraction turns to love soon enough for many toddlers.

Authors, illustrators, storytellers, parents and publishers all over the world have believed in the positive influence of picture books on kids, so much that they were aghast when a New York newspaper ran a controversial story late last year suggesting that picture books were obsolete.

Author Dianne de Las Casas read the article, and also saw how the digital age had ushered an unprecedented amount of ebooks with devices like the iPad, the Nook color and the Kindle Fire.

She decided it was time to celebrate picture books in their printed format and so, together with a group of authors and illustrators, created an initiative to designate November as the ‘Picture Book Month’. Their website is a delight for book lovers. While people have been celebrating the event in the United States of America, it has caught on in several other parts of the world too, thanks to cyberspace.

Book readings, storytelling sessions and other book-related activities have been keeping young ones engaged and glued to books.

In India, where millions of children do not have access even to the most basic of needs — food, water, shelter, education, health facilities — picture books come way down in the list of priorities. Illustrator Elizabeth O Dulemba has another set of basics. “People need three things to survive,” she says in her blog, “food, shelter and wonder.”

And wonder is what picture books offer. Even with the low importance given to storybooks and picture books for children, the industry in India is not doing badly. Some Indian publishers are trying to cater to the very young with eye-catching picture books based on Indian themes and context and in Indian languages — ACK’s Karadi, Pratham Books, Ekalavya, Tulika, to name a few. But most bookshops in cities have only Western rhyme, alphabet and number books that serve as picture books, almost all in English.

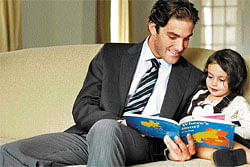

The trend is the same in the big book fairs. Picture books in Indian languages are a wonderful means to introduce children to vernacular flavours. It is exciting that ACK has given us Eric Carle’s The Grouchy Ladybug and other delightful picture books as English-Hindi bilinguals and both Tulika and Pratham Books have brought out several bilingual combinations. Pictures transport children into unseen worlds and expand their imaginations as nothing else can. Picture books also come with a default comfort factor — the adult reader. This person, a parent, grandparent or a kindergarten teacher usually, immediately puts the child in a safe place physically.

Researchers have found that there is endless learning that happens during such times in early childhood. Apart from the learning through the book, the bonding too helps in myriad ways in the child’s development. Says David Ezra Stein, author of Interrupting Chickens that won a 2011 Caldecott Honor, and one of the promoters of the Picture Book Month, “I’ll never forget the experience of sitting on a beloved lap and having a whole world open before me: A world brought to life with pictures and a grown-up’s voice.”

What makes the picture book different from other children’s books is of course the quality of pictures and the attention to detail that goes in. A good picture will illustrate more than just the words of the author. Apart from the intended story, there may be many stories running parallel, which the child can imagine for herself. For instance, during a reading of the ever-popular Lion and the Rabbit, a child wanted to know if the lion would eat up the frog seen inside the well. She wanted to know whether frogs had teeth. While the story had no mention at all about a frog, the child soon went off excitedly on a story about the frog and its possible adventure.

The National Book Trust celebrated Book Week for children during the week starting November 14, Children’s Day. The Bookaroo Literature Festival being held in New Delhi from November 25-27 started its celebration of books by inviting writers and illustrators to have storytelling and book-related activities through the Bookaroo In the City (BIC) programme that started in early November.

The schools range from NGO-run schools in bastis to Municipal Corporation of Delhi schools, from B-category schools to the schools that have every facility available to school children. While not all books promoted during this festival were picture books for the very young, many of them did the same function — give children wings to soar on and pictures to dream about. No wonder Yuyi Morales, illustrator of Ladder to the Moon, refers to picture books as her “light and path.”