Fourteen years after a bloody farmland agitation in Nandigram changed West Bengal's political landscape, and plans to set up a chemical hub there went kaput, residents of this once-obscure constituency now desperately want industrial development to stop their menfolk from leaving home in search of work.

Battle lines have been redrawn in Nandigram, a place that shook the foundations of the mighty 34-year-old Left Front regime in the state and propelled the TMC to power in 2011, as Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee is all set to take on her protege-turned-adversary Suvendu Adhikari in this assembly segment on April 1.

Although the discrete constituency stands polarised along political and communal lines, parties and locals, notwithstanding the differences, believe that setting up of industry would be welcomed with open arms unlike 2007, when it had faced stiff opposition.

"An industrial hub here would not just generate employment in the area but also ensure our children live with us. If not in Nandigram, industrial growth in surrounding areas would also be of help. The youth won't have to venture out searching for jobs," said Ajit Jana, an aged resident of Adhikaripara here, said.

Joydeb Mondal of Gokulnagar, who works in a factory in Gurugram, feels if people are given good compensation for the land acquired, they wouldn't resist industrial development.

"Nandigram movement is a thing of the past. If people get good compensation and locals get to earn through direct and indirect employment, it won't be a problem anymore," Mondal, 32, said.

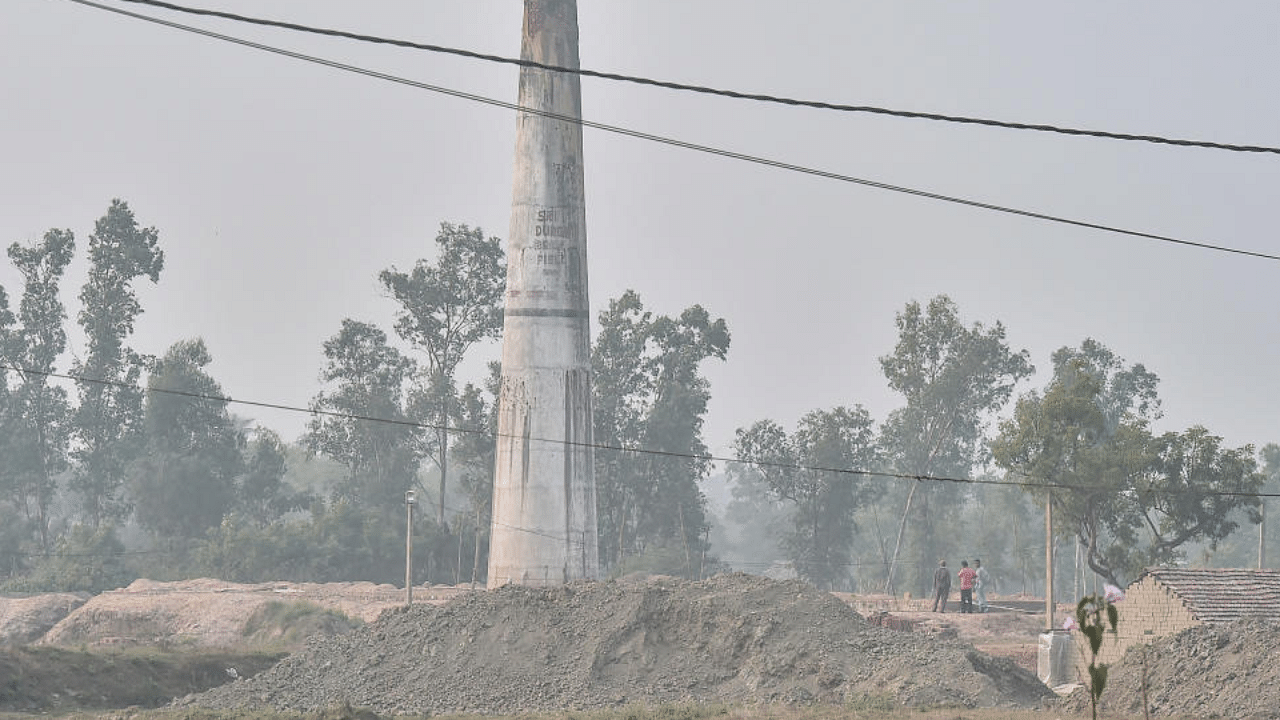

Nandigram in coastal Purba Medinipur district is a one-crop place owing to the high salinity in its water.

"As this is a single-crop region and the land is very fragmented, people here want industry -- be it garment-based on agri-based," a TMC panchyat samiti member, who did not wish to be named, said.

Nonetheless, with no industrialist setting foot in the area after the Special Economic Zone (SEZ) project was scrapped due to the agitation, which left an unspecified number of people dead, including 14 in a police firing, Nandigram continues to be a primarily agricultural-driven economy as it supplies rice, shrimp farming vegetables and fresh fish to adjoining localities.

The Bhumi Uchhed Pratirodh Committee (BUPC), which spearheaded the 2007 protest, had people from disparate political ideologies as members. Activists of the TMC, Congress, the RSS and even disgruntled workers of the Left parties, along with locals, had waged a united struggle against the then Left government, forcing Indonesia's Salim group to scrap its plans to set up a 10,000-acre chemical hub.

Asked what prompted this change in the mindset of locals after fourteen years, Bhabani Das, a former Bhumi Uchhed Pratirodh Committee (BUPC) leader, said the transition was waiting to happen as the monthly income of most families who have stayed put in Nandigram does not exceed Rs 6000.

Also read: BJP believes in crushing, conquering: Yashwant Sinha joins TMC ahead of West Bengal polls

"Most households have at least one member who works in some other state. Here, a job means cultivating lands, shrimp farming or jobs under the MNREGA scheme. The youths now have academic degrees, unlike their parents, and they don't take interest in agriculture," Das said, as she set off on a rally organised to mark Nandigram Diwas.

Every year, The TMC observes Nandigram Diwas on March 14, as a mark of tribute to the 14 people who died in the police firing, while opposing land acquisition in 2007.

Also, the COVID-induced lockdown was an eye-opener, as hundreds of migrant labourers, who had to return home from cities far away, spent sleepless nights worrying about ways to make ends meet in this town, Das added.

"People have understood that the TMC had misled them. Without industry, there can't be any development," CPI(M)'s Purba Medinipur district president Niranjan Sihi said.

The TMC supremo, having got a whiff of popular sentiments, has promised to turn Nandigram into a model village and ensure no one is left unemployed in the area.

The BJP, which is leaving no stone unturned to defeat Banerjee, has, on its part, promised to set up industries in the area to ensure unemployed youths get jobs.

Hopes are afloat that the new government would be reviving the shipyard project in Nandigram's Jellingham area, on the banks of Hooghly river -- a venture abandoned after the exit of the Left.

Locals are also waiting to see a wagon components manufacturing unit come up at Jellingham, a promise made by Banerjee during her tenure as the railway minister.

"We would ensure that the Jellingham shipyard project gets started. The TMC did nothing for the locals over the past 10 years. We would take everybody along and usher in industrial growth in the state," Nabarun Nayak, BJP Tamluk district unit president, told PTI.

Local TMC leader Abu Taher, however, lashed out at the saffron party, and sought to know why the BJP government at the Centre did nothing to revive the Jellingham project in the last seven years.

Political analyst Biswanath Chakraborty feels that the demand for industrial growth could prompt the Left's revival in the constituency.

"The Left could spring back to prominence in Nandigram, where it was once pushed to the corners," he said.

Suman Bhattacharya, another political observer, said this change in mindset was bound to happen, as people's aspirations usually grow with time.

"In 2007, a farmer was probably happy with what he earned from his farmland and agricultural produce. But his children, who are educated, are not satisfied. They want jobs, they don't want to get into agricultural work," he said.