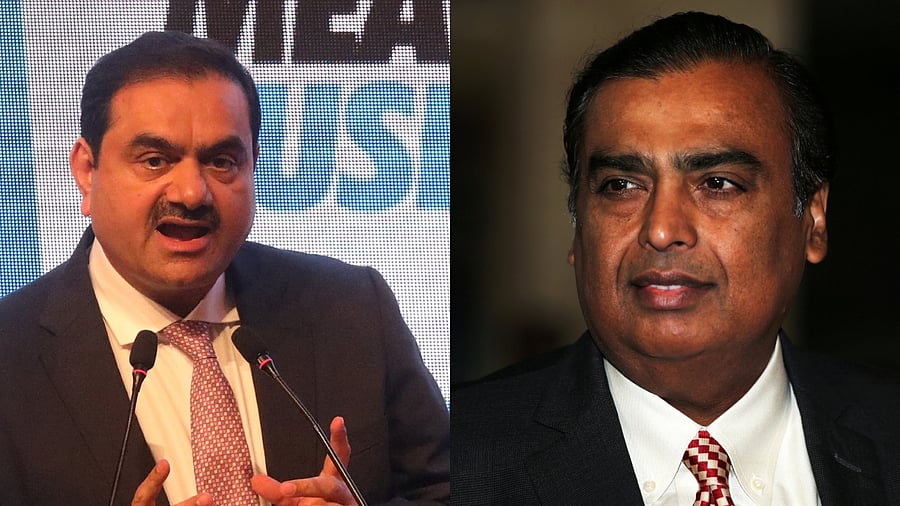

Adani is not the only India billionaire buying up media operations. Mukesh Ambani, acquired Network18 Group — giving him access to more than 70 media outlets followed by at least 800 million Indians.

Credit: Reuters File Photos

By Advait Palepu and Chris Kay

An exodus of star anchors. Fawning coverage of India’s political leaders. Newsroom censoring of reporters who ask the government tough questions on the economy, public policy and conflict.

These are some of the changes journalists attribute to a management shakeup at New Delhi Television Ltd., which billionaire Gautam Adani acquired more than a year ago through a hostile takeover. Ahead of India’s national elections, NDTV has morphed into a government mouthpiece, according to current and former employees. They say the channel — akin to India’s CNN — has shed its reputation as one of the country’s most fearlessly independent news outlets.

“Journalism is dead,” said Ravish Kumar, a popular anchor who resigned from NDTV ahead of Adani’s takeover. These days, he said in an interview with Bloomberg News, “the only use of newspapers and channels is to create propaganda for Narendra Modi.”

On the face of it, India still has a vibrant media. With more than 20,000 newspapers and 300 TV channels, the industry reflects the vast diversity of a democracy with 1.4 billion people. But to many journalists, leadership changes at NDTV and diluted coverage across India illustrate how Prime Minister Modi has effectively brought to heel a once-riotous media. Newsrooms are being reshaped, they say, by India’s richest press barons, many of whom are close to the ruling party and depend on millions of advertising dollars from the government.

Adani, one of Asia’s richest tycoons and a longtime friend of Modi, is a high-profile case study. After his conglomerate acquired NDTV, the channel commissioned an adulatory nine-part documentary about Modi and now lands exclusive interviews with senior officials in the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. Just a few years ago, sit-downs with top cabinet members were rare and managers fretted about federal agencies raiding NDTV’s offices.

Pressure to avoid sensitive topics extends beyond Modi, according to nearly a dozen current and former employees, who asked not to be identified to protect their jobs in the industry. After a US short seller accused the Adani Group of “brazen fraud” in January of last year, the conglomerate shed $150 billion in market value at one point. NDTV’s new leaders ordered journalists not to cover the story, according to three employees, even as Adani-related shares plunged on the stock market and local and foreign media outlets published reports. Over the next 48 hours, reporters pushed back, eventually convincing senior editors to publish an article from a newswire.

There’s much at stake for Adani. NDTV recently launched two new regional channels and several more are in the works. In December, Adani also purchased Indo-Asian News Service, one of India’s oldest newswires.

“The owners of key media houses are known to have close relations with the ruling BJP party and the current prime minister,” said Somdeep Sen, an associate professor at Denmark’s Roskilde University. That “close alliance,” he added, “has been an important means of shaping and controlling India’s media.”

The Adani Group’s media operation “is politically neutral and is deeply committed to supporting professional and independent journalism and NDTV will be no exception,” said a spokesperson in a written reply to Bloomberg’s queries.

The “insinuation” that there was deliberate delay in NDTV’s coverage of the Hindenburg incident is “misinformed and based on biased information,” the spokesperson said.

With elections expected in April, many Indian journalists across the board predict deferential coverage of Modi as he seeks a third term in office. Over the past year, more than a dozen senior staff have resigned from NDTV over directives to avoid storylines that entangle government allies, current and former employees say. Fear of eroding press freedom runs alongside a broader concern about a democratic backslide in India. Human rights watchers accuse the BJP of weakening minority rights, fueling religious intolerance, and undermining independent institutions, including the media.

In a country accustomed to major corporate scandals and questions around the quality of economic data, increasing restrictions on the press could add to investor risks in India. Hasnain Malik, a Dubai-based strategist at emerging-market research outfit Tellimer, said “infringements of rights” become a problem when there’s a high risk of sanctions, in particular.

But for now, at least, Modi’s India remains a hot investment destination. Last month, the prime minister greeted hundreds of local and global business houses at a biennale summit in his home state of Gujarat. Many lavished him with praise.

Ahead of the NDTV takeover in 2022, Adani called his investment in media a “responsibility” rather than a business undertaking.

“Independence means if government has done something wrong, you say it’s wrong,” he told the Financial Times. “But at the same time, you should have courage when the government is doing the right thing every day. You have to also say that.”

For years, NDTV cultivated a reputation as an aggressive and anti-establishment voice.

Founded in the 1980s by husband-and-wife team Prannoy and Radhika Roy, the company steadily built out its content as India’s economy liberalized. In 1995, NDTV became the first private producer of national news and soon after launched India’s first 24-hour channel.

“We had a very clear mission that we would question and we would hold power to account,” said Maya Mirchandani, a former NDTV foreign affairs editor and now an associate professor at Ashoka University. “I loved the place.”

Previous governments have also been harsh on the press. During the 21-month Emergency rule imposed by former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi from the Indian National Congress party, members of Modi’s BJP famously said India’s press “crawled” when they were asked to “bend.” Following the 2014 election of Modi, many reporters and commentators, including from the political opposition, have said an “undeclared Emergency” is in place and India’s fourth estate has less scope to push back against censorship. The country’s constitution doesn’t grant ironclad media freedom like in the US. Instead, ill-defined amendments have provided plenty of leeway for federal and local governments to muzzle journalists.

Under Modi, state agencies have increasingly used money laundering laws and tax inspections to pressure editors and media owners perceived as antagonistic or “anti-national.” By one estimate, 15 journalists are currently facing charges under India’s anti-terror laws.

Intolerance towards reporters isn’t limited to the BJP. This month, journalists in West Bengal accused the police and the ruling Trinamool Congress party of blocking access to report on civil unrest in the Sundarbans. In 2022, a journalist in the central state of Chhattisgarh was arrested for writing satirical stories about the Congress-led government.

In turn, India’s media freedom ranking has steadily declined, falling to 161 out of 180 countries in the latest survey from the World Press Freedom Index.

After the ranking was released, S Jaishankar, India’s foreign minister, rejected the report, saying something was “fundamentally wrong” with the methodology. Modi, too, has pushed back. During a June visit to the US, the prime minister said in a rare press conference that he was “really surprised” to hear India’s commitment to democratic values questioned.

Yet many of the most successful channels today publish reliably pro-government content, including Rajat Sharma’s India TV and Arnab Goswami’s Republic TV. Others, including Aroon Purie’s Aaj Tak and India Today, are frequently laudatory of Modi. “He has the Midas touch,” read a tweet from India Today’s official handle on X, formerly Twitter.

Credit: Screengrab fromX/@aroonpurie

India TV, Republic TV and India Today didn’t respond to requests for comment.

Concerns about dwindling avenues for dissent are further complicated by changes to the media business. Like in many parts of the world, a subscription model hasn’t taken off in India, forcing outlets to rely on government and corporate advertising to stay afloat, said Kalyani Chadha, a journalism professor at Northwestern University.

“That’s a really significant problem,” she said.

Adani is not the only India billionaire buying up media operations. Mukesh Ambani, a tycoon whose corporate interests are often aligned with the government, acquired Network18 Group — giving him access to more than 70 media outlets followed by at least 800 million Indians.

Of course, many media organizations, including Bloomberg News, are owned by wealthy entrepreneurs. In that respect, India is no different. But what does set the nation apart is that figures like Ambani and Adani are chief executors of the government’s development goals in industries as varied as renewable energy and digital commerce.

Ambani’s Reliance Group didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Adani Group’s takeover of NDTV was achieved through complex corporate maneuvering, buying out the channel’s biggest creditor and other shareholders, and boosting the conglomerate’s ownership stake to nearly 65 per cent. One estimate pegged the cost of the deal at more than $100 million.

During a broadcasting break in August 2022, Kumar, who anchored shows in Hindi, picked up his phone and scrolled through a barrage of messages about the leadership change. A few months later, Kumar announced his departure, calculating that his editorial independence would be curtailed.

“NDTV will never remain the same,” he remembered thinking.

At first, the Adani Group vowed to turn the channel into an international media group. Sanjay Pugalia, the head of Adani’s media arm and a veteran journalist, was appointed executive director. He told senior staff that he didn’t want to get involved in journalistic decisions or even sit in the New Delhi newsroom, according to people familiar with the matter.

But on January 2, days after the Roys resigned from NDTV’s board citing a change in leadership, Pugalia took over the couple’s corner office. Journalists said the new managers’ initial reluctance to cover the short seller’s fraud allegations against Adani that month illustrated the complexity of juggling competing priorities. Though NDTV eventually republished articles from the Press Trust of India, Reuters and Bloomberg News, staffers said harder-hitting pieces on the saga were blocked.

Pugalia didn’t respond to requests for comment.

A standoff grew within NDTV. Pugalia hired two managing editors, sidelining more experienced staff who were part of the organisation for over a decade. Several reporters said the new managers micromanaged coverage, dropped sensitive stories and instead opted for soft features.

Coverage of opposition politicians was also fraught. In October, when the BJP accused opposition lawmaker Mahua Moitra of graft and misconduct, NDTV ran multiple discussions on the topic. Employees said panelists were handpicked during the first few weeks, leveling personal attacks against Moitra that went unchallenged. It was only when the company brought in a new editor that balance was restored, the employees said, with senior politicians from Moitra’s party also participating in interviews and panel discussions.

The lawmaker was eventually expelled from Parliament. She attributed that decision to her criticism of the government and the Adani Group, including how NDTV covered the story. Government officials attributed Moitra’s expulsion to sharing the password to the parliamentary website with someone on the outside.

“Multiple reach outs were made to TMC to participate,” said the Adani Media Group spokesperson, referring to Moitra’s party. “We made sure there were independent voices and representation from other opposition parties.”

Key talent also left the company, though managers linked the attrition rate to restructuring. In May, Sarah Jacob, a journalist with over 20 years of experience at NDTV, anchored a segment called How PM Shows Respect Towards Women. The next day she resigned. In a statement, she thanked the Roys for “building what was one of India’s great media institutions.”

“Every management transition and transformation leads to employee churn,” said the Adani Media Group spokesperson, adding that NDTV has been on a post-takeover hiring spree with more than 200 staffers added and the attrition rate dropping by 58 per cent from before the change in ownership.

For Kumar, leaving NDTV — and watching colleagues follow — signals the end of an era for Indian journalism. Since resigning, he’s struggled to find a place in another mainstream newsroom. Instead, he’s become something of a recluse, working from an apartment on the outskirts of India’s capital and filming YouTube videos covering topics traditional outlets will no longer touch.

Kumar’s following is still huge — 8.59 million subscribers — but he worries that the government could try to block his channel or arrest him. He hesitates to leave his apartment complex.

“This is the kind of environment where everybody thinks that they’re being monitored,” Kumar said.

For now, India remains a country where freedom of expression is often tolerated in larger doses than Asian nations like Thailand or Singapore. Unlike China, social media in India is still a relatively freewheeling space. Some opposition-controlled states also offer more varied coverage, according to Sadanand Dhume, a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington.

“The government hasn’t been able to snuff out all criticism simply because of India’s size and federalism,” he said.

But that freedom is fragile even in vernacular or regional media.

A few years ago, India’s information ministry temporarily cut off the broadcast of a prominent news channel in the southern state of Kerala for covering a mob attack between Muslims and Hindus in India’s capital. The government justified their decision by saying the segment was “critical toward Delhi Police and R.S.S.,” using an acronym for a far-right Hindu group.

The fear remains, Dhume said, that India’s “little islands of free expression” could sink beneath “the rising tide of government repression.”