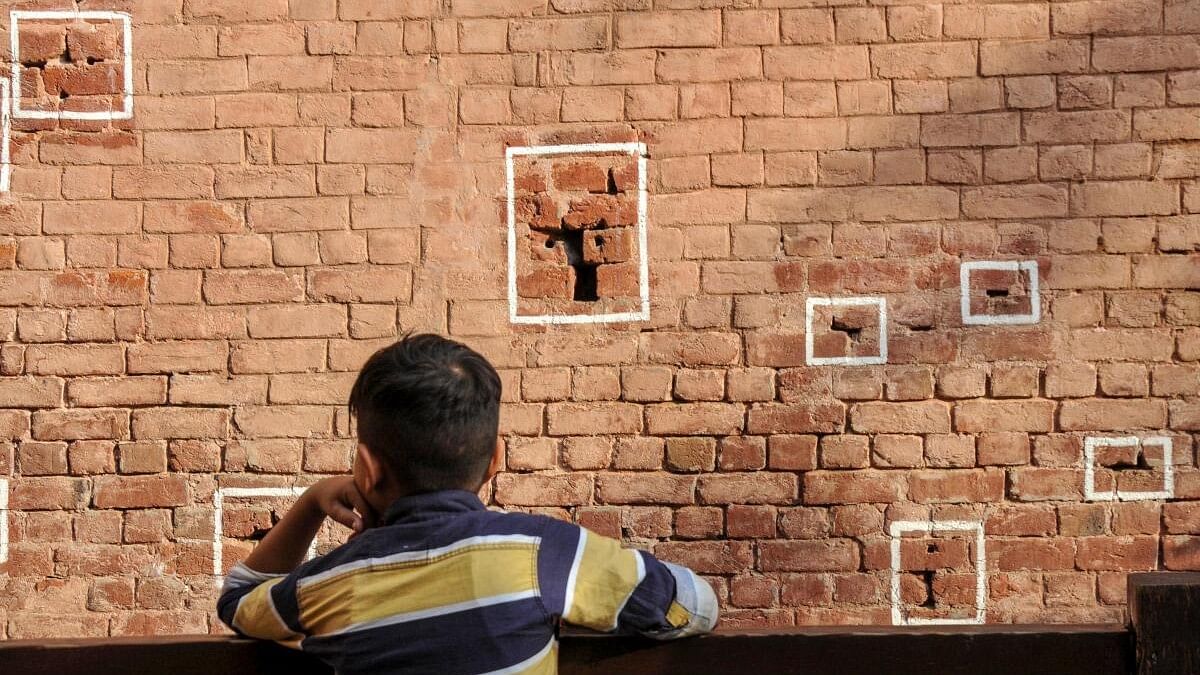

People visit Jallianwala Bagh on the eve of 104-years of the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre, in Amritsar, Wednesday, April 12, 2023. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, which took place on April 13, 1919, the Baisakhi day, after Brigadier-General Reginald Edward Harry Dyer ordered 50 British Indian Army soldiers to open fire on a crowd marks one of the darkest moments in Indian history.

Credit: PTI Photo

The British government provided compensation to the families of Indians affected by the Jallianwala Bagh massacre, but a recent study by historian Hardeep Dhillon indicates that the distribution of compensation was underpinned by racism.

Following the bloodbath, the imperial administration prioritized European claims, valuing them at a significantly higher rate compared to those of Indians, with a difference of 600 times, as per the recent publication.

Jallianwalah bagh massacre

On April 13, 1919, General Dyer, a British officer, led troops to the peaceful gathering in Amritsar's Jallianwala Bagh, where protestors were opposing the Rowlatt Act. Without discrimination, Dyer ordered firing upon the crowd, resulting in numerous casualties, including women and children.

This incident wasn't isolated; it unfolded amidst widespread protests against oppressive British policies across colonial Punjab in early 1919. While protestors targeted colonial infrastructure like railways, telegraph lines, and banks, the British responded with martial law, employing excessive force in Delhi, Bombay, Lahore, Amritsar, Kasur, and Gujarat.

The Research: Aim and Publication

Historian Hardeep Dhillon, an assistant professor of History at the University of Pennsylvania, recently conducted research delving into the aftermath of the Jallianwala Bagh massacre. The study illuminates how the discriminatory distribution of compensation stemmed from legal frameworks established by the British following the 1857 revolt.

Published in The Historical Journal under the title 'Imperial Violence, Law, and Compensation in the Age of Empire, 1919-1922,' the findings shed light on the origins and expansion of modern compensation mechanisms during colonialism. Dhillon emphasized in an interview with Indian Express that her objective was to underscore the connection between historical legal structures and contemporary practices of compensation and reparations.

Main findings

District magistrates in Punjab exercised their discretion in disbursing a total of R. 523,571 to widows and children of five deceased Europeans in Amritsar and Kasur, as well as Europeans affected during the protests. Individual compensations for Europeans varied, with the highest at approximately R. 300,000, the lowest at R. 30,000, and the median at R. 80,000. Conversely, the Government of India sanctioned one-time payments for Indians not exceeding Rs 500 for a family member's death and around Rs 300 for qualifying permanent injuries.

A discreet distribution of Rs 14,050 was made to Indian subjects through confidential inquiries, aiming to discourage further requests and limit precedents, the study reveals. Despite subsequent payments to Indians after legal and political pressure, the disparities persisted, with compensation for 700 individuals amounting to less than half of what a few European recipients received, highlighting enduring racial biases in valuing lives.

The process that British officials undertook to arrive at the final figure

The India Office in London directed the Government of India to investigate the widespread violence of early 1919, following amnesty granted to British officials, Dhillon explains to the publication.

In the 1920 final report, the Punjab Disturbances Committee, divided along racial lines, saw four European members justifying brutal tactics used by British officers, opposed by three Indian members.

"The Government of India, with a 4:3 division based on race, claimed that its officers were legally entitled to use violence in all situations, including actions such as forcing colonial subjects to crawl on their bellies, whipping, caning, and making arrests, with only two exceptions. The first exception was Jallianwala Bagh, and the second was Gujranwala, a Punjabi locality where British pilots dropped bombs on colonial subjects from planes," Dhillon tells IE.

Indian legislators, leveraging colonial findings, demanded equal compensation for Indian families affected in Amritsar and Gujranwala, mirroring that of European subjects in 1919. Armed with evidence of disparate treatment, Indian legislators sought acknowledgement and compensation, within strict geographical limits, as British officials aimed to avoid setting precedents and refused to express regret.

History- the most politically charged discipline

“Without understanding these processes and their ongoing impact, we continue to perpetuate imperial logic in the present. Therefore, it is essential to decolonize the parameters, including the legal parameters, that we have inherited. Historical scholarship plays a crucial role in this process, which is why history is often the most politically charged discipline in many countries, and the first field of knowledge that imperial and authoritarian governments seek to control,” Dhillon explains.