On the occasion of the 73rd Independence Day of the country, Prime Minister Narendra Modi appealed to the people to make the country free from single-use plastics (SUPs) and to work towards this mission wholeheartedly. This has also brought plastics into the national spotlight. While debates around the ban being a good proposition or bad are going on, it is important to know the extent of the problem in the first place.

As per a 2015 assessment by the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), 6.92% of the municipal solid waste (MSW) in the country comprises of plastic waste. With extrapolation of the plastic waste generation data from 60 major cities, this study estimated that around 25,940 tonnes per day (tpd) of plastic waste is generated in India. Delhi, Chennai, Kolkata, Mumbai, Bengaluru, Ahmedabad and Hyderabad are among the top generators, while Gangtok, Panjim, Daman, Dwarka and Kavaratti are lowest in the index. Of this, around 15,600 tpd, that is 60% gets recycled, still leaving behind nearly 10,000 tonnes of it, which eventually ends up in the drains, rivers, seas, or simply as the litter that we see everywhere around us. The study also revealed that approximately 70% of plastic packaging products are converted into plastic waste in a short span. It was found that almost 66% of plastic waste comprised of mixed waste—polybags, multilayer pouches used for packing food items, etc. (belonging to HPPE/ LDPE or PP materials), sourced mainly from households and residential localities.

While India’s per capita plastic consumption at 11 kg per annum is low as compared to other countries — a tenth of the US and less than a third of China’s -- as per estimates, India’s trajectory of plastic consumption and plastic waste in the years ahead is set to increase. The plastic processing industry in 2018 estimated that polymer consumption from 2017 to 2022 is likely to grow at 10.4%; nearly half of which would be single-use plastic.

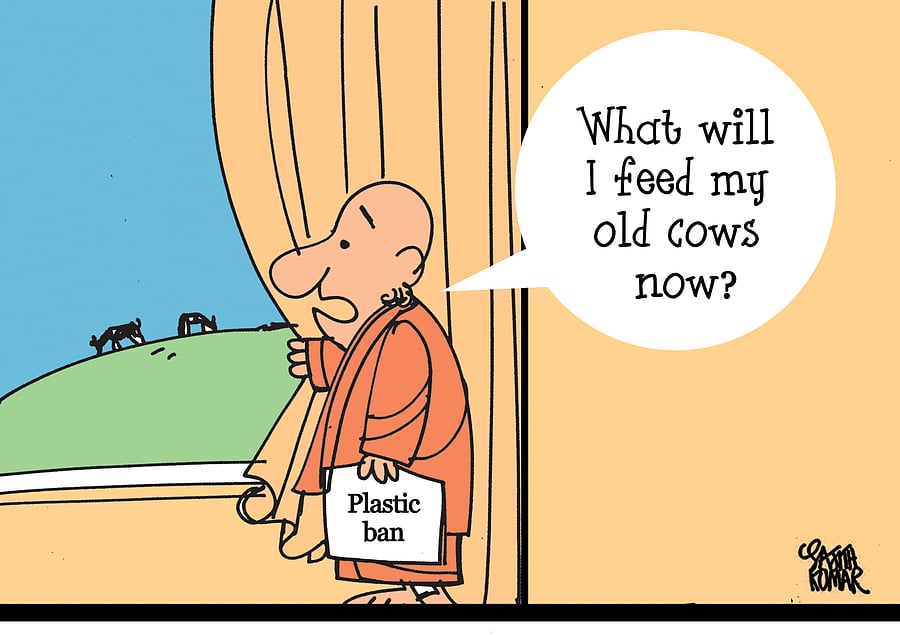

In the last few years, 29 states and UTs have imposed bans on plastic, but this has been merely focused on carry bags.

Considering the given scenario, how will the single-use plastics ban work in the country? Also considering we are literally living in the ‘Age of Plastics’, how will sound implementation of a SUP ban work out?

A clear definition

As per the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) report, single-use plastics are products that are commonly used for plastic packaging and include items intended to be used only once before they are thrown away or recycled. These include, among other items, grocery bags, food packaging, bottles, straws, containers, cups and cutlery. In India, the Ministry of Chemicals and Fertilizers formed a committee in January 2019 to define SUPs and prepare a roadmap for its elimination. In the four committee meetings that have been held since, however, the definition has remained elusive. There is an urgent, dire need to agree on a definition of SUPs, along with a clear guideline defining the scope and challenge of the problem and a clear approach and steps that could be taken on the ground.

Baseline and inventory

What fraction of our plastic waste is single-use plastics? What part of this fraction is packaging waste, cutlery items, carry bags, PET bottles, etc? These are some of the numbers we need in order to assess the scale of such waste as well as look for clear alternatives for such plastics. There needs to be an initiative at the level of the states to push cities to make inventories of their dry waste, considering that the composition of our waste has changed drastically with more plastics in the last several years. Only then can we identify which are the most problematic SUPs and assess the extent of their impact before imposing bans. Such a study has not been done so far.

Segregation

How can one push for recycling and better dry waste management if segregation is not done right? Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 is not pushing much for segregation. Imposing a ban is only a part, not the whole solution. However, if cities segregate waste into three fractions – wet, dry, and domestic hazardous waste -- and then the dry fraction is further sorted, and if municipalities create infrastructure in terms of material recovery facilities or sorting stations, dry waste can be sorted into over 70-80 fractions. This then has value and a market and would not end up as litter. However, this has had only marginal success. We need to source segregate — end to end. Also, recycling as a silver bullet solution will not work unless there are technological interventions to make it sustainable.

Informal is critical

A bigger debate over the SUP ban issue is on the fact that more than a million workers will lose jobs. As per a 2018 estimate, there are over 3,500-plus organized recycling units and over 4,000 unorganized units. Approximately, six lakh workers are directly employed and another 10 lakh are informal workers. This is a critical number, and there needs to be a clear roadmap on how these workers would be transitioned to any other industry. Also, a phased ban on items could be explored.

Economic alternatives

Presently, some items do have alternatives. For instance, straws. We can easily do away with the straw culture. However, paper straws can be looked at as a viable alternative. For another, plastic carry bags could be easily replaced by cloth/jute bags, however not sourced from virgin cotton material (considering that would have a higher carbon footprint) but from upcycled textiles/cloth. Also, municipalities could look into investing in plate/crockery bank initiatives to replace disposable cutlery, which is a huge menace. Green Protocols in Kerala (a state-wide initiative to discard the use of SUPs during public and private events using crockery banks) and crockery banks in Ambikapur, Chattisgarh, are some examples that have become successes.

Also, letting go of small water bottles (below 250 ml) or PET cups could be explored, considering they are not even enough for a single serving and become discards in seconds. Multi-layered packaging is another menace, however there is no real alternative for it currently. According to the industry body FICCI, 42% of plastic waste is multi-layered packaging. However, systems to segregate and collect multi-layered packaging can be channelized for co-processing, making laminates or making roads and these alternatives can be easily explored.

Is ban the solution?

Though the idea of limiting the inflow by imposing a ban sounds worthy, the question on the economics, accessibility and availability of alternatives remains unanswered. The Centre and states need to focus on a clear definition, baseline study and then evaluate possible actions by using a combination of regulatory, economic and voluntary tools involving various stakeholders. For multi-layered packaging, apart from extended producer responsibility (EPR) which should have schemes such as Deposit Refund Scheme (DRS), consumer responsibility should also be worked upon by targeted campaigns and social engineering tools to make people aware of the concerns and alternatives to plastics.

Industry should be given a timeline for transition via tax rebates and by keeping certain eco-friendly materials tax-free. This, along with regular compliance, monitoring and enforcement, will help India eventually substantially eliminate single-use plastics and plastic waste in general.

(The writer is Programme Manager, Environmental Governance (Waste Management), Centre for Science and Environment, New Delhi)