Shreevallabhan shifts his weight from one foot to the other, his gigantic head bobs from side-to-side, swaying in the heat of the Thiruvananthapuram summer. To the untrained eye, the 22-year-old elephant's behaviour suggests happiness. Vallabhan’s mahout of 10 years, Biju, affectionately says the elephant is ‘dancing’ in tune to music.

This is far from the truth. “Only captive elephants sway like this. In fact, it is a sign of psychological distress and high levels of stress,” says Avinash Krishnan, a wildlife biologist who heads A Rocha, a global family of conservation organisations.

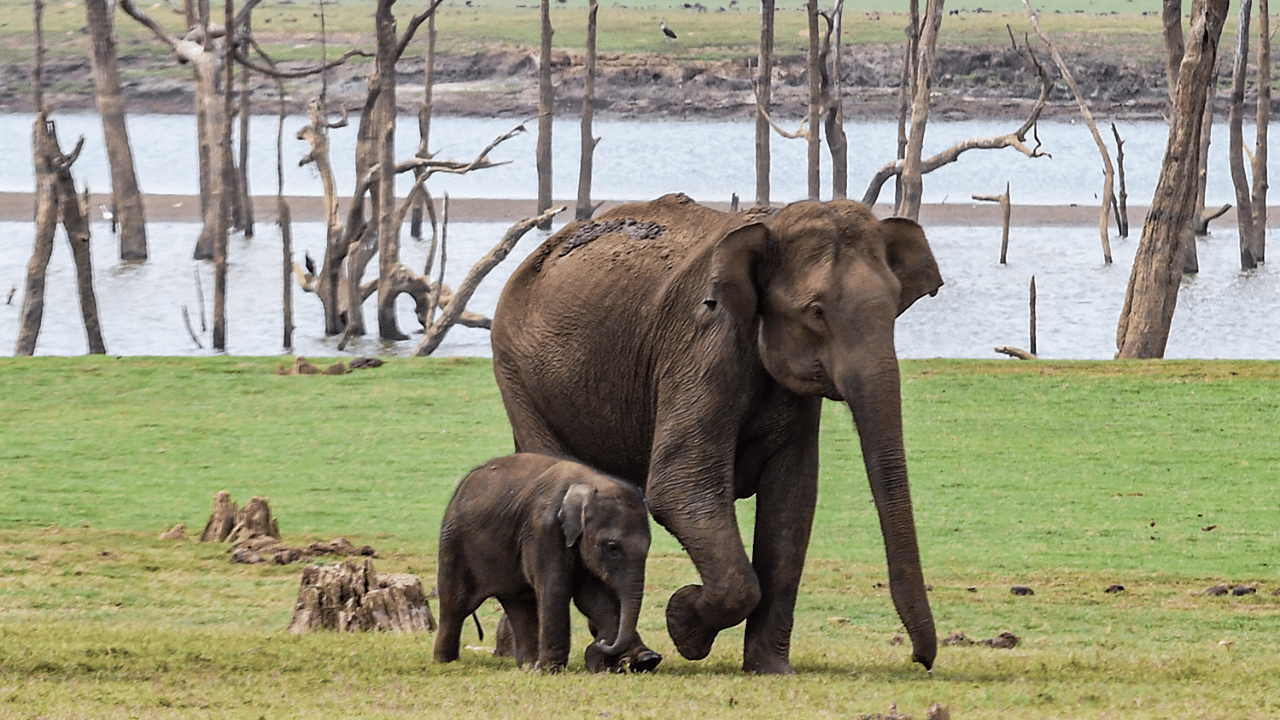

India has about 2,675 captive elephants according to an RTI filed by animal welfare activist Antony Rubin in 2019. A majority of these elephants, about 1,821, are under private ownership. They are used for entertainment, tourism and religious purposes. To put this into perspective, India has about 29,964 wild elephants — nearly 50% of the world’s Asiatic elephants.

Unlike their wild counterparts, elephants in captivity get little or no exercise, are on improper diets, are often subjected to noise and disturbance and live in isolation, because of which they suffer from a range of diseases.

Given the abysmal conditions of care, a task force appointed by the Ministry of Environment and Forests in 2010 had unequivocally recommended the phasing out of elephants in commercial captivity.

Presently, the commercial trade of elephants is prohibited under the WPA, 1972. Ownership of elephants is also limited to those in possession of elephants before the law came into force. Wildlife conservationists fear that the implementation of the Wildlife Protection Amendment Bill, 2021, might undo decades of progress towards ensuring the welfare of the keystone species.

With the inclusion of a new clause under Section 43 of the law, the amendment permits those who have ownership certificates to transfer elephants. The ambiguous definition of ‘live elephants’, which could mean both captive and wild elephants, could also pose a significant risk to the population of jumbos, explains Sreeja Chakraborty, an environmental lawyer and founder of Living Earth Foundation.

“The amendment does not dwell into the manner or means of procuring such live elephants, it will encourage the capture of wild elephants. The section grants effective legal sanctity to commercial trade in live elephants,” she says.

Tabled in the winter session of the Lok Sabha, the Bill is now pending before the parliamentary standing committee headed by Rajya Sabha Member Jairam Ramesh.

A similar move in the past to legalise the sale of ivory from Namibia and Zimbabwe to China and Japan provides an interesting parallel. A ‘one-time legal sale’ was allowed to clear 102 tonnes of ivory stockpiles. The move backfired dramatically, poaching rose by 65% according to Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) data.

With a similar mismatch in the demand for elephants and the number of captive animals actually present, the Union government may inadvertently be opening the floodgates for the illegal trade of live elephants.

Threat to conservation

“Any threat to elephant conservation activities must be viewed seriously. The survival of our forests depends on it,” explains M N Jayachandran, a former member of the Kerala State Animal Welfare Board. “Forests would completely collapse without them. Elephants are important ecosystem engineers. They make pathways in densely forested habitats that allow passage for other animals,” he says.

Once in captivity, these behemoths live constricted lives. Megharaj, a mahout of six years at Karnataka’s Dubare Elephant Camp, is acutely aware of this. “Mahouts and the public may be attached to elephants but private custodians rarely let elephants live in the environment they enjoy,” he says.

Elephants in government camps such as Dubare have habitually been in conflict with humans, even killing a few. Pointing to the elephant receiving a scrub in the Dubare river, he says, “He has killed about five people.”

“The government trains ‘troublemaking’ or elephants recovered from captivity in kraals (training enclosure) only if the relocation efforts fail,” says Saswati Mishra, Additional Principal Chief Conservator of Forests. These elephants are used in forest patrolling, tiger capture and elephant capture for forest department purposes.

Captive elephants in Dubare are bathed, fed and then taken out into the forests, providing them with some semblance of normalcy.

But in private care, elephants are not so fortunate.

“Elephants are wild animals. They can be tamed but not domesticated,” explains Krishnan, who adds that the conditions of the forest can never be recreated in captivity.

Thousands of captive elephants spend their lives in chains, confined to one place. “But the anatomy of an elephant is not conducive to standing still for long periods of time,” says R Sukumar, an ecologist. Compared to their natural habitats, where they walk about 20-40 km every day, elephants in captivity hardly walk a kilometre or two. Invariably, many captive elephants under private ownership develop knee issues, arthritis or foot rot.

Elephants are also highly intelligent creatures with complex social lives. Their existence in isolation, secluded from the rest of their species, is particularly torturous. As a result, captive elephants are not the ‘gentle giants’ many perceive them to be, leading to violent encounters with human populations. Sree Vallabhan has a notorious reputation in Malayankeezhu Sree Krishna Temple. He has run amok on several occasions, even injuring and killing people during past festivities.

Then there is the matter of diet. In forests, these pachyderms feed on close to 67 different species of plants. “What elephants get to eat in temples is not in any way scientific. They are fed palm and coconut fronds. Many times their diet does not have much variation. They are also given sweets in the form of prasadam etc,” says M N Jayachandran. As a result, these animals have digestive issues, developing fatal twisted intestine conditions, and suffer from obesity.

With this deprivation in mind, the Project Elephant Guidelines from 2003 sought to standardise space, food and transportation requirements for owners. But caring for elephants on the ground is not easy, as Nayaz Pasha, a mahout with 20 years of experience at Dubare Elephant Camp, will tell you.

Other than the prohibitive costs, there is also the danger that comes with looking after these jumbos. “Their moods can be unpredictable. There is always a threat to the life of people and property,” he says.

Those in violation of Project Elephant guidelines rarely face any legal consequences or have their elephants confiscated. A forest official in Karnataka, on the condition of anonymity, says that given the amount of workload on grassroots forest department staff, monitoring the conditions of elephants under private ownership is rare. However, Saswati assures that the department takes up complaints of improper care and cruelty on a priority basis and ensures that the elephant is secure.

A flawed system

And even though commercial trade is banned under the current framework, many elephant owners who are eager to sell often ‘lease’ or gift elephants. For instance, close to 320 elephants in Assam have been leased out to private owners in southern India from 2003.

The WPA 1972 intended to take stock of the number of captive elephants in private ownership and eventually phase out the possession of elephants. The Project Elephant guidelines on captive elephant care intended to make conditions more humane. The guidelines also mandated that microchips be inserted under the skin of elephants in captivity to check the sale of wild elephants.

But activists say the history of the transfer of elephant ownership is not maintained uniformly. “Ownership certificates are routinely faked,” says Krishnan. In other instances, ownership certificates of dead elephants are used by owners who have acquired another one in its place. “I have seen certificates that specify the age of the elephant as 40-50 years, and the elephant in front of me is just 12-15 years old,” he says.

Ramesh Amala Srinivasan, a captive elephant rehabilitator, knows of 10 temples in Tamil Nadu in the queue to acquire elephants. To meet the demand for live elephants, illegal trade continues unabated in Bihar, Jaipur and Assam.

“There are even cases where calves have been captured in the wild for private ownership,” says B K Singh, former Principal Chief Conservator of Forests.

While the intentions behind legalising the commercial trade of elephants is unclear, Jayachandran believes that the government should tread delicately while dealing with a Schedule I wild animal such as the elephant. “The trade of elephants involves cruelty. There is no other way. It also jeopardises the population of wild elephants which today is under risk by habitat loss, fragmentation of corridors and a range of other factors.”

Megharaj witnesses the outpouring of love for elephants at the camp on a daily basis. People ask to ride atop elephants, hug them and receive blessings, even though they are aware that this is a rehabilitation camp.

“What people don’t understand is that they love the forests,” he says. Elephants deserve to be in the forests, and forests deserve elephants.

(With inputs from Arjun Raghunath in Thiruvananthapuram)

Check out DH's latest videos