China's Belt & RoadXi's big dream: Strategically converges domestic imperatives for growth with global leadership aspirations

Last Updated IST

China's Belt & Road

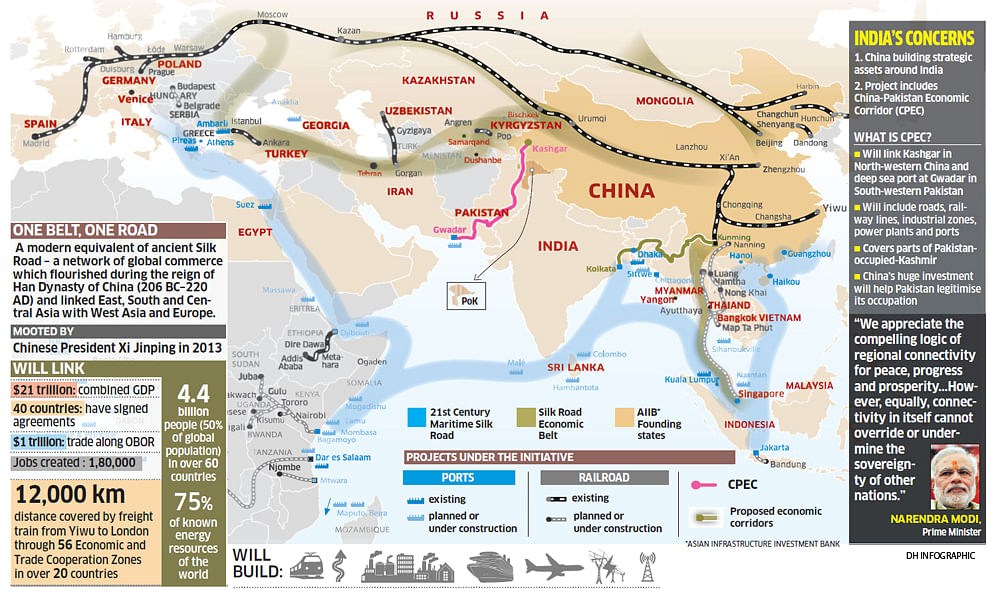

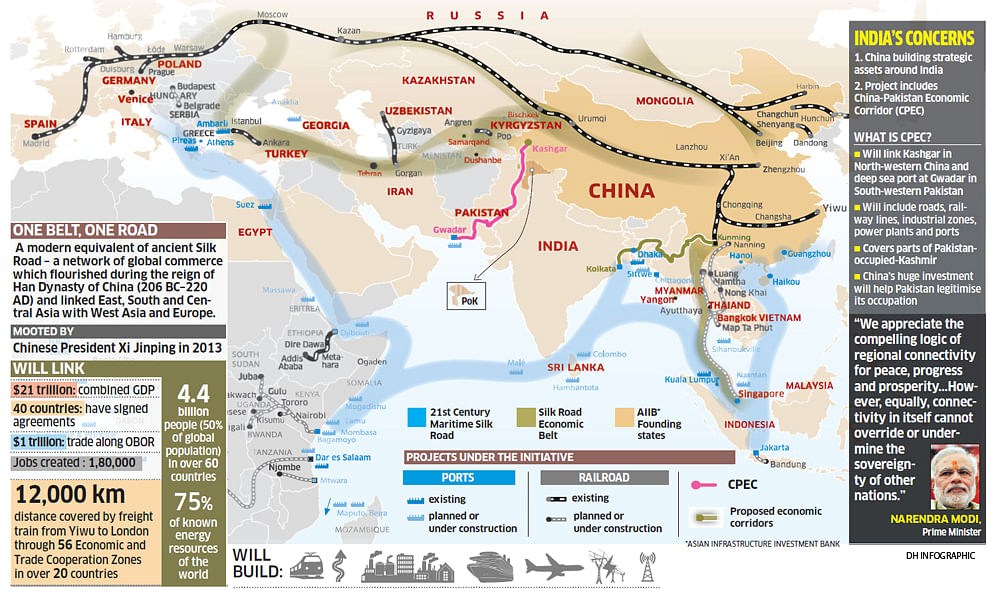

The Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, launched in late 2013, is the signature project of Chinese President Xi Jinping. Now re-designated as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it is one of the most ambitious programmes ever rolled out by any government.

The Belt and Road Forum being held in Beijing on May 14-15 showcases its achievements to 28 foreign heads of state and government, as also delegations from other countries. No official participation from India has been announced so far.

Backed by huge resources, BRI has acquired overarching importance in foreign policy and domestic domains of China. As it has Xi’s personal imprimatur, a wide range of ongoing projects and activities have been folded into the grand narrative of the BRI, with its contours still evolving.

Though said to cover nearly 60 countries, BRI was conceived entirely by China without any prior consultation with potential partner countries, and certainly not with India. It strategically converges domestic imperatives for growth and economic rebalancing with global aspirations of leadership.

China needs new growth engines for its slowing economy, and must deploy its huge surplus capacities in sectors such as steel, machinery and infrastructure. As it moves up the value chain, it requires new markets and more productive use of its foreign exchange reserves.

Other considerations include internationalisation of the Renminbi, development and stabilisation of its restive western regions, and protection of sea routes carrying its oil needs and other merchandise.

Thus, the Chinese government is unfurling two separate narratives of the BRI – the domestic story highlighting internal gains and the external ‘win-win’ story of great economic benefits to ‘partner countries’ through more infrastructure, trade and investment. In actual fact, the track record of Chinese companies in, say, Africa and Sri Lanka is far from being stellar and is generating backlash. Projects are mostly being funded through not-so-concessional loans and many white elephants with dubious economic value and viability are being reared. Recent reports suggest that investments under the BRI do not quite match the hype, and may have even declined in 2016 over the previous year.

The BRI is more than about connectivity across land and maritime space. It is also a geostrategic initiative aimed at shaping China’s periphery and carving out a continental-cum-maritime realm with China as the anchor, ‘sutradhar’ and central player. It is an initiative for achieving China’s geopolitical objectives by binding neighbouring countries more closely to its growth. China is steadily putting in place a universe of institutions led by it and will progressively seek to influence the setting of rules and standards in its extended periphery.

Above all, BRI is a key instrument to realise the ‘Chinese dream’ of ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. This involves fostering the country’s role as a leading power in the world, a leader which helps shape and guide the global governance system, is a rule setter, and safeguards its core interests. Chinese officials are strenuously playing down the strategic component of BRI, repackaging it as an ‘initiative’ rather than a strategy. However, the change of nomenclature does not alter the nature of this grand enterprise.

Given the geopolitical underpinnings of BRI, an important question is whether India can ‘join’ it as a junior partner. Our response to BRI is determined by our assessment of its nature and its implications, and, not surprisingly, has not been enthusiastic. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the flagship project of both land and maritime dimensions of BRI and its most advanced component, passes through Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir.

India’s reservations regarding CPEC go beyond our sovereignty-related concerns. From China’s perspective, the main drivers of CPEC are geostrategic, as it lacks economic rationale. It will bolster strategic and military capabilities of both China and Pakistan and affect India’s security environment. This can stem from the likely Chinese naval presence at Gwadar port, military use of the upgraded Karakoram Highway, closer strategic linkages between China and Pakistan, and so on. India has repeatedly conveyed its strong objections regarding CPEC to China, including at the highest level. As a country which projects its territorial claims as its ‘core interests’, China should have no difficulty in appreciating India’s sensitivities.

Apart from CPEC, India also has misgivings about the manner in which BRI is being pursued in its neighbourhood. Many commentators have pointed out that the unstated objective of the Maritime Silk Road is to consolidate China as a maritime power in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. For instance, several ports are being developed and would be under Chinese operational control, raising valid concerns in India.

Unilateral initiative

Beginning with External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj’s meeting with Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Beijing in February 2015, the Chinese have been told that BRI is their unilateral initiative, not involving prior consultation with India, and that our endorsement should not be expected.

However, there is space to work together. India, like Japan and the Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean), is pursuing connectivity and developmental projects in Asia. As such, it undertakes joint projects with many countries in the Asian region, including China. This is a pragmatic approach based on objectives and interests that coincide. For example, convergence of interests led to India joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as the second largest shareholder after China. Significantly, India was fully involved in the multilateral process of crafting the architecture of AIIB.

Similarly, the Indian industry could explore BRI projects that are open for international competitive bidding, as also upcoming AIIB-funded projects. India can also utilise infrastructure being developed by China. For instance, India, Iran and Afghanistan are building a maritime road-rail link to Central Asia through Iran’s Chabahar port. This could link up with Chinese-built routes to access Central Asia and Russia as well as Europe. This will be an example of ‘win-win cooperation’, as the Chinese are fond of saying.

India and China are also part of the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, a sub-regional economic cooperation initiative. While China has been repositioning it as a part of BRI, it commenced much earlier with all participants as equal partners and should not be considered as a sub-loop under the mega Chinese initiative. India neither needs to endorse nor be part of China’s re-labelling of some ongoing initiatives.

In the larger regional theatre, however, both countries can cooperate where there are synergies, as they are doing in the AIIB. India’s substantive concerns on the BRI need to be addressed, and New Delhi expects China to take its sensitivities into account while formulating plans. Clearly, there is room for closer strategic consultations between China and India on the objectives, contours and future directions of this mega enterprise.

(The writer, a former Indian Ambassador to China, is director, Institute of Chinese Studies, New Delhi, and a Distinguished Fellow of Vivekananda International Foundation)

The Belt and Road Forum being held in Beijing on May 14-15 showcases its achievements to 28 foreign heads of state and government, as also delegations from other countries. No official participation from India has been announced so far.

Backed by huge resources, BRI has acquired overarching importance in foreign policy and domestic domains of China. As it has Xi’s personal imprimatur, a wide range of ongoing projects and activities have been folded into the grand narrative of the BRI, with its contours still evolving.

Though said to cover nearly 60 countries, BRI was conceived entirely by China without any prior consultation with potential partner countries, and certainly not with India. It strategically converges domestic imperatives for growth and economic rebalancing with global aspirations of leadership.

China needs new growth engines for its slowing economy, and must deploy its huge surplus capacities in sectors such as steel, machinery and infrastructure. As it moves up the value chain, it requires new markets and more productive use of its foreign exchange reserves.

Other considerations include internationalisation of the Renminbi, development and stabilisation of its restive western regions, and protection of sea routes carrying its oil needs and other merchandise.

Thus, the Chinese government is unfurling two separate narratives of the BRI – the domestic story highlighting internal gains and the external ‘win-win’ story of great economic benefits to ‘partner countries’ through more infrastructure, trade and investment. In actual fact, the track record of Chinese companies in, say, Africa and Sri Lanka is far from being stellar and is generating backlash. Projects are mostly being funded through not-so-concessional loans and many white elephants with dubious economic value and viability are being reared. Recent reports suggest that investments under the BRI do not quite match the hype, and may have even declined in 2016 over the previous year.

The BRI is more than about connectivity across land and maritime space. It is also a geostrategic initiative aimed at shaping China’s periphery and carving out a continental-cum-maritime realm with China as the anchor, ‘sutradhar’ and central player. It is an initiative for achieving China’s geopolitical objectives by binding neighbouring countries more closely to its growth. China is steadily putting in place a universe of institutions led by it and will progressively seek to influence the setting of rules and standards in its extended periphery.

Above all, BRI is a key instrument to realise the ‘Chinese dream’ of ‘great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation’. This involves fostering the country’s role as a leading power in the world, a leader which helps shape and guide the global governance system, is a rule setter, and safeguards its core interests. Chinese officials are strenuously playing down the strategic component of BRI, repackaging it as an ‘initiative’ rather than a strategy. However, the change of nomenclature does not alter the nature of this grand enterprise.

Given the geopolitical underpinnings of BRI, an important question is whether India can ‘join’ it as a junior partner. Our response to BRI is determined by our assessment of its nature and its implications, and, not surprisingly, has not been enthusiastic. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), the flagship project of both land and maritime dimensions of BRI and its most advanced component, passes through Pakistan-occupied-Kashmir.

India’s reservations regarding CPEC go beyond our sovereignty-related concerns. From China’s perspective, the main drivers of CPEC are geostrategic, as it lacks economic rationale. It will bolster strategic and military capabilities of both China and Pakistan and affect India’s security environment. This can stem from the likely Chinese naval presence at Gwadar port, military use of the upgraded Karakoram Highway, closer strategic linkages between China and Pakistan, and so on. India has repeatedly conveyed its strong objections regarding CPEC to China, including at the highest level. As a country which projects its territorial claims as its ‘core interests’, China should have no difficulty in appreciating India’s sensitivities.

Apart from CPEC, India also has misgivings about the manner in which BRI is being pursued in its neighbourhood. Many commentators have pointed out that the unstated objective of the Maritime Silk Road is to consolidate China as a maritime power in the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. For instance, several ports are being developed and would be under Chinese operational control, raising valid concerns in India.

Unilateral initiative

Beginning with External Affairs Minister Sushma Swaraj’s meeting with Foreign Minister Wang Yi in Beijing in February 2015, the Chinese have been told that BRI is their unilateral initiative, not involving prior consultation with India, and that our endorsement should not be expected.

However, there is space to work together. India, like Japan and the Association of South East Asian Nations (Asean), is pursuing connectivity and developmental projects in Asia. As such, it undertakes joint projects with many countries in the Asian region, including China. This is a pragmatic approach based on objectives and interests that coincide. For example, convergence of interests led to India joining the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) as the second largest shareholder after China. Significantly, India was fully involved in the multilateral process of crafting the architecture of AIIB.

Similarly, the Indian industry could explore BRI projects that are open for international competitive bidding, as also upcoming AIIB-funded projects. India can also utilise infrastructure being developed by China. For instance, India, Iran and Afghanistan are building a maritime road-rail link to Central Asia through Iran’s Chabahar port. This could link up with Chinese-built routes to access Central Asia and Russia as well as Europe. This will be an example of ‘win-win cooperation’, as the Chinese are fond of saying.

India and China are also part of the Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor, a sub-regional economic cooperation initiative. While China has been repositioning it as a part of BRI, it commenced much earlier with all participants as equal partners and should not be considered as a sub-loop under the mega Chinese initiative. India neither needs to endorse nor be part of China’s re-labelling of some ongoing initiatives.

In the larger regional theatre, however, both countries can cooperate where there are synergies, as they are doing in the AIIB. India’s substantive concerns on the BRI need to be addressed, and New Delhi expects China to take its sensitivities into account while formulating plans. Clearly, there is room for closer strategic consultations between China and India on the objectives, contours and future directions of this mega enterprise.

(The writer, a former Indian Ambassador to China, is director, Institute of Chinese Studies, New Delhi, and a Distinguished Fellow of Vivekananda International Foundation)