The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP) performed abysmally in the recent assembly polls in Uttar Pradesh. Its vote share plummeted to 12.88 per cent, and 290 of its candidates forfeited their security deposits. It could win only one seat in the 403-member house. In Punjab, where Dalits account for 32 per cent of the electorate, the BSP won one seat with a 1.77 per cent vote share.

The results prompted many to wonder if it is the end of the road for one of India’s most successful political startups of the last four decades? Could it also mark the sunset of Dalit-led parties rooted in the Ambedkarite assertion of identity?

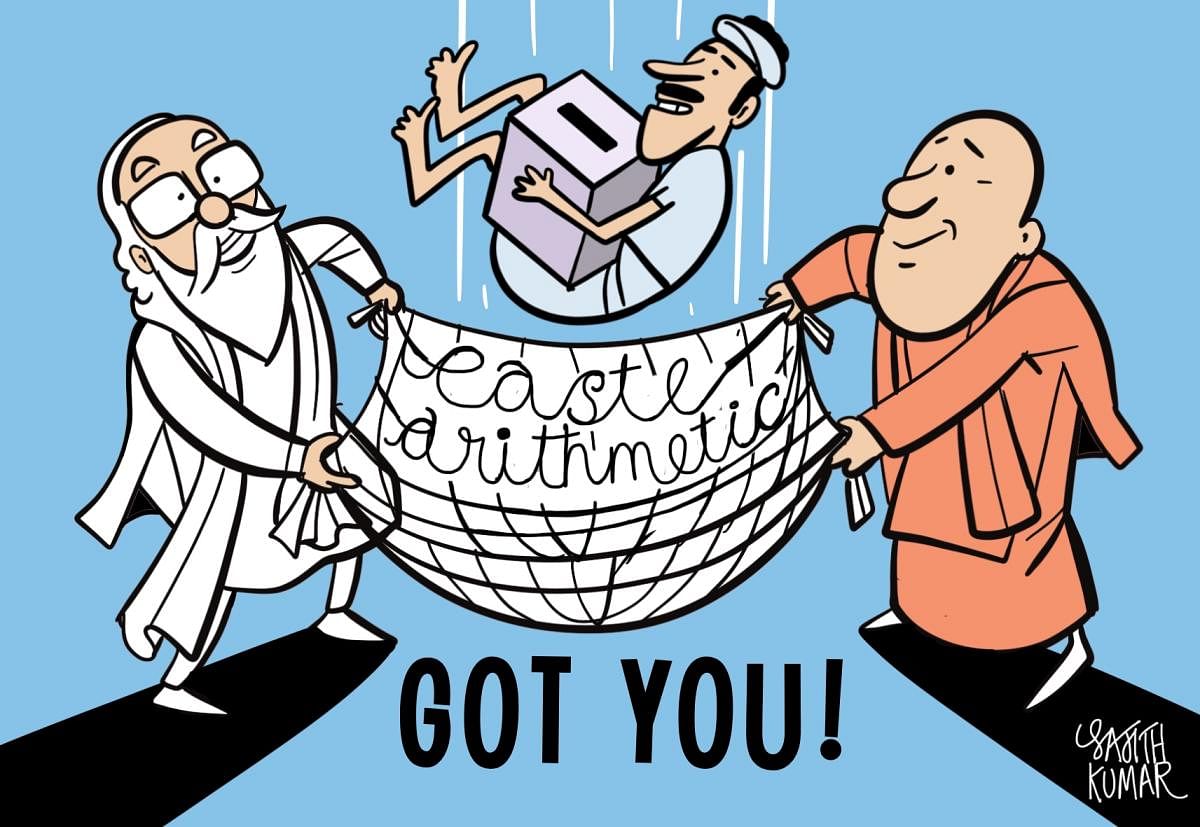

Pollsters are still debating whether the BJP or the SP benefited from the BSP’s decline in Uttar Pradesh. In Punjab, results made it evident that nearly all sections of its society, including Dalits, saw hope in the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP). A decade back, the AAP had displaced the BSP in the Dalit imagination in the Delhi Assembly polls of 2013.

The BSP leadership, however, seems incapable of honest analysis. In a statement issued three days after the results, Mayawati attributed her party’s loss to a media conspiracy. She alleged that the media projected the SP as the BJP’s principal opponent in Uttar Pradesh.

But Dalit activist Ashok Bharti believes the seeds of the BSP’s worst performance since 1989 lay in its most spectacular success in 2007. The BSP had, in 2007, with over 30 per cent votes, formed a single-party majority government in Uttar Pradesh. “The media had failed to discern any wave for the BSP in the run-up to the 2007 polls. But after the polls, the BSP bought into the media narrative that attributed its victory to a Dalit-Brahmin alliance,” Bharti, who heads NACDOR, which fights for Dalit and tribal rights, says.

Consequently, the BSP ended up making fundamental changes to its political strategy. It shed its focus on “bahujan”, those socially, economically and culturally deprived sections, to start talking about “sarvajan”, including the upper castes.

Some of the BSP’s second-rung leaders – disciples and followers of its founder Kanshi Ram from the All India Backward and Minority Communities Employees Federation (BAMCEF) and Dalit Shoshit Samaj Sangharsh Samiti (DS4) – resisted the ideological shift. Kanshi Ram had groomed them as leaders of their respective non-Yadav OBC communities and Pasis, the second most significant Dalit caste after the Jatavs in Uttar Pradesh. They were shown the door over the past few years, along with some of its Muslim leaders. The trend continued until the 2022 polls.

Kanshi Ram had founded the political movement that stoked Dalit consciousness by reminding them of Shambuka and Eklavya, seen as victims of Brahminism in Hindu mythology. But the BSP started invoking Ram and Parashuram, promising to work for the “betterment of Sudama”, a symbolism for the poor and marginalised among Brahmins. The BSP appointed Brahmins as its respective leaders of the two Houses of Parliament – Satish Chandra Mishra in the Rajya Sabha and Ritesh Pandey in the Lok Sabha. Interestingly, days after the UP poll results, Girish Chandra Jatav replaced Pandey.

Meanwhile, the Sangh Parivar was busy making inroads among Dalits, as Badri Narayan of Prayagraj-based GB Pant Social Science Institute has detailed in his book, ‘Republic of Hindutva’, with its social welfare and embracing of historical icons of Dalits and OBCs. The beneficiaries of the Narendra Modi government’s welfarism, such as the Ujjwala scheme and free rations, were the poorest, mostly Dalits. With Mayawati-led BSP losing its ideological moorings, there were more takers for the Sangh’s vision of “samajik samarasta”, or social harmony, instead of the Ambedkarite assertion of caste identity.

If it were more alert, the BSP’s leadership would have discerned in Delhi a decade back how parties led by upper castes planned to eat into its support base. The 2013 assembly polls in Delhi saw the AAP sweep nine of the city-state’s 12 reserved seats. Delhi’s sizeable Dalit electorate found the AAP’s ‘broom’, its election symbol, and its anti-corruption plank appealing. The BSP vote share declined from 14.05 per cent in 2008 to 5.35 per cent in 2013, 1.3 per cent in 2015, and a pitiful 0.71 per cent in 2020.

A year later, the BSP couldn’t win a single seat in the Lok Sabha. In UP, the BJP swept most SC reserved seats, as it did in the 2017 assembly polls, winning 69 of the 84 SC reserved seats to the BSP’s two. In 2022, the BJP and its allies won 63, while the SP and its partners bagged 20.

Also read: SP alliance lost UP assembly polls because of dishonesty and cunningness of BJP: Shivpal Yadav

Five months after the 2014 LS polls, Modi, now the prime minister, stood outside the Valmiki Temple in Delhi’s Mandir Marg with a broom in hand. After taking the oath of office on Wednesday, AAP’s Punjab CM Bhagwant Mann had portraits of Bhagat Singh and B R Ambedkar in his office.

But Dalit activists and intellectuals, like Bharti, are hopeful of the future. They believe the current phase is a gestation period before dynamic leaders emerge to voice issues that concern backward castes and Dalits, something parties with upper-caste leaderships and support bases will not. Dilution of educational and job reservations with increased privatisation and atrocities on Dalits are examples.

On Tuesday, Jitendra Pal Meghwal, a Dalit youth, was murdered in Rajasthan by an upper-caste man. According to the initial police investigation, his murderer couldn’t tolerate Meghwal’s changed standard of living after he secured a government job, but most of all, the Dalit youth’s upturned handlebar moustache.

Check out DH's latest videos