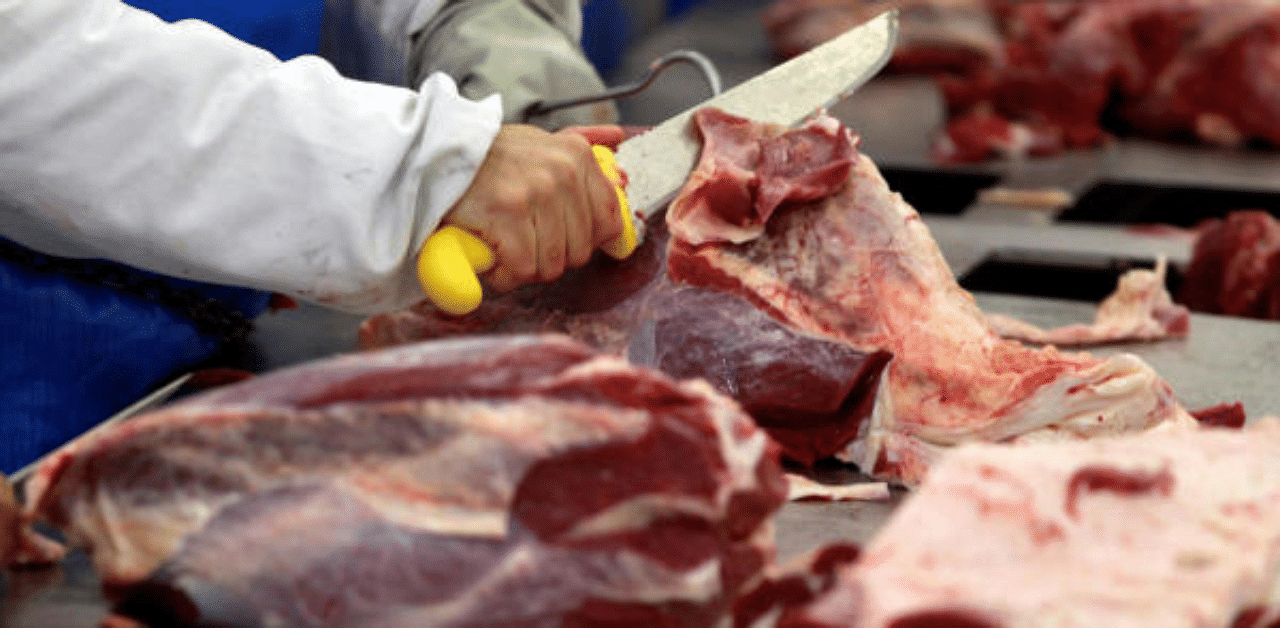

An analysis of fat residues in ancient ceramic vessels from settlements of the Indus Civilisation in present-day Haryana and Uttar Pradesh suggests that the prehistoric people of the time consumed meat of animals like cattle, buffalo, sheep, goat, and pigs as well as dairy products.

The study, published in the Journal of Archaeological Science, involved extraction and identification of fats and oils that have been absorbed into ancient ceramic vessels during their use in the past.

Based on the analysis, the scientists, including those from the University of Cambridge in the UK, unravelled how these ancient vessels were used and what was being cooked in them.

"Our study of lipid residues in Indus pottery shows a dominance of animal products in vessels, such as the meat of non-ruminant animals like pigs, ruminant animals like cattle or buffalo, and sheep or goat, as well as dairy products," said study co-author Akshyeta Suryanarayan former PhD student at the Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge.

Suryanarayan, who is currently a postdoctoral researcher at CNRS, France, said her team found a predominance of non-ruminant animal fats in the vessels -- even though the remains of animals like pigs were not present in large quantities.

"It is possible that plant products or mixtures of plant and animal products were also used in vessels, creating ambiguous results," she added.

Despite the high percentages of the remains of domestic ruminant animals found at these sites, the archeologists said there is very limited direct evidence of the use of dairy products in the vessels.

"The products used in vessels across rural and urban Indus sites in northwest India are similar during the Mature Harappan period (c.2600/2500-1900 BC)," said Cameron Petrie, senior author of the study from the University of Cambridge.

"This suggests that even though urban and rural settlements were distinctive and people living in them used different types of material culture and pottery, they may have shared cooking practices and ways of preparing foodstuffs," Petrie said.

The scientists believe the findings highlight the resilience of rural settlements in northwest India during the transformation of the Indus Civilisation, and during a period of increasing aridity.

"There is also evidence that rural settlements in northwest India exhibited a continuity in the ways they cooked or prepared foodstuff from the urban (Mature Harappan) to post-urban (Late Harappan) periods," Petrie said.

He said this was particularly during a phase of climatic instability after 2100 BC, suggesting that daily practices continued at small rural sites over cultural and climatic changes.

"These results demonstrate that the use of lipid residues, combined with other techniques in bioarchaeology, have the potential to open exciting new avenues for understanding the relationship between the environment, foodstuffs, material culture, and ancient society in protohistoric South Asia," Suryanarayan concluded.