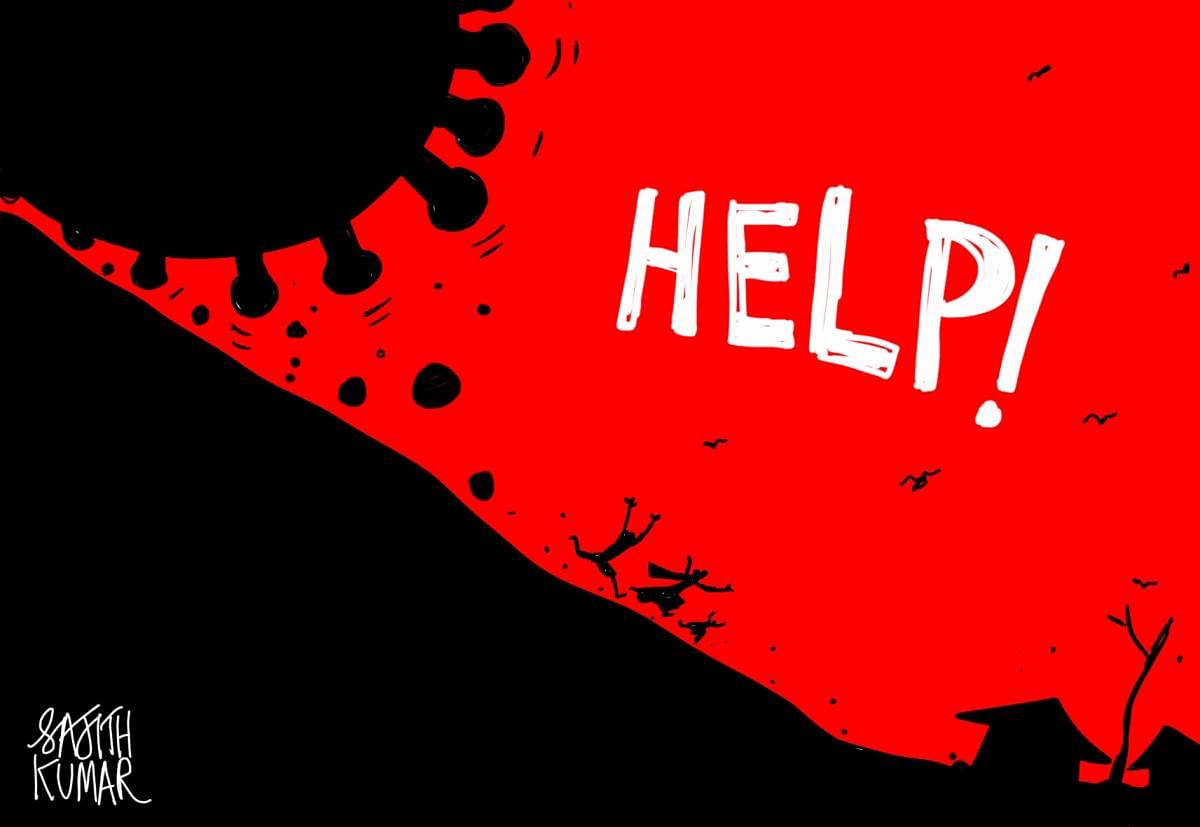

As the second surge of the Covid-19 epidemic moves towards rural India, the Centre has taken the first step to ramp up the health infrastructure in villages to tackle the rampaging virus by issuing a detailed what-to-do guideline for the administration. But experts familiar with rural health opine that not only the guidelines came late in the day, but it also relies too much on the urban experience without factoring in rural realities.

To make the matter worse, implementation of the government’s plan to augment surveillance in villages would depend on few lakhs of poorly paid and inadequately trained ASHA and ANM workers as no efforts have been made in the past few months to recruit locals as grassroot health workers despite serious staff shortage in most of the states. Taking a cue from the urban experience, the guidelines put emphasis on home isolation and advised the administration to prepare 30-bed Covid Care Centres to manage such mild cases where home isolation is not feasible.

“This is not practical as most of the rural homes don’t have rooms with attached toilets. Home isolation is possible in urban families, but unlikely to work in a village where it’s better to move a person to a dedicated covid care facility. You can’t have the same strategy for urban and rural settings,” pointed out Soumyadeep Bhaumik, a medical doctor and public health specialist at The George Institute for Global Health, Delhi. “Moreover, since the majority of the rural families are joint families, the aim should be to prevent more infections once the first person in a family is infected by SARS-CoV-2. It may not be possible if the infected person stays with the family. A dedicated Covid Care Centre with links to a hospital and adequate ambulance service is a better option.”

While the government guidelines emphasise extensive surveillance using rapid antigen tests and dedicated OPD clinics to screen influenza-like illness and severe acute respiratory infection cases, the big question is who would carry out the work on the ground? “We have nearly 10 lakh ASHA workers, 13-14 lakh Anganwadi workers and 3.5 lakh auxiliary nurses and midwives. Besides, there are people from the agriculture department and panchayat raj institutions, who can be roped in for the work,” said V K Paul, NITI Ayog member and chairman of the government task force on Covid-19.

Also Read | Covid-19 tests rural health services

In Rajasthan, where every second case is now being reported from the villages, ASHA workers pointed out that the honorarium of Rs 2,700 paid by the government was grossly inadequate. They are not paid extra for Covid duties, even though for the initial four months during the first wave, they were paid Rs 1,000 rupees extra. “There has been no increment and no facilities. They don’t even give us a PPE kit. We have risked our lives and several of us contracted Covid-19”, says Sita Devi, an ASHA worker in Jaipur rural.

In Uttar Pradesh, where Covid-19 infections have spread to nearly one third of its 97,000 villages, nearly 1.5 lakh ASHA workers are paid even less - around Rs 2,500 per month.

“We face a lot of difficulties in conducting surveys. Sometimes people behave rudely and shoo us away. We also have families and of course we are scared of contracting the disease,’’ said one Asha worker in Uttar Pradesh, who refused to reveal her identity. In neighbouring Madhya Pradesh, the emoluments are little better. Nearly 75,000 ASHA workers in MP are paid around Rs 10,000 per month including all incentives. The government has not announced any additional incentive for them but some basic training on testing and administering medicines was imparted by the district administration.

In each of the states, ANMs are paid better with experts pointing out that the salaries for the ANM come from the Central kitty. For instance, in Uttar Pradesh, the full-time ANMs earn Rs 30,000 per month while those on contract earn between Rs 8,000-Rs 10,000. “In Rajasthan, the major crisis lies in rural areas. The primary health centres in villages look fashionable, but the reality is that they are not utilised properly,” said Narendra Gupta of Jan Swasthya Abhiyan. “What is worrying us is the spread of infection in rural areas. We are increasing the testing capacity there. We are all set to introduce rapid antigen tests to screen the suspected patients,” added Raghu Sharma, Rajasthan Health Minister.

Testing strategy

Such a change in testing strategy lies at the core of the Centre’s Covid-19 plans for the rural areas. The aim is to extensively increase the RAT to screen people so that those tested positive could be isolated and taken care of. Those tested negative would be retested with a RTPCR only if they have symptoms. The Centre aims to carry out 45 lakh tests by June, of which 27 lakh – 60% of testing - would be rapid tests. The RAT booths are to be set up at 1.87 lakh sub-centres besides the thousands of primary health centres and hundreds of community health centres at the block level. Also, mobile RAT booths are being planned for difficult terrain. The missing element is the manpower factor.

In UP where an official survey detected Covid-19 cases in nearly 29,000 villages, close to 33% posts of doctors and 45% posts of nurses are lying vacant. On paper, doctors are posted at PHCs, CHCs and district hospitals, but most of them don’t regularly work there, especially in the remote areas, and visit once or twice a week. At some places, the PHCs are also dysfunctional. Rural Madhya Pradesh’s 1,400 primary health centres and 700 community health centres face more than 50% shortage of doctors and nurses.

In December 2019, the then Kamal Nath government in Madhya Pradesh had prepared a proposal to fill 2,500 vacant posts in rural health centres but before the health directorate could move forward on the proposal, the Congress government fell in March 2020. The incumbent Shivraj Singh government has not filled those vacancies.

“There is no commitment from the government to increase manpower for public health in rural areas. The number of sanctioned posts is less than the required posts and even the sanctioned posts have not been filled up,” said T Sundararaman, former executive director at the National Health Systems Resources Centre.

While the southern states fare better in terms of rural health infrastructure and human resources, the situation is really bad in states like Bihar, Jharkhand and Uttar Pradesh. “In my ancestral village in Motihari district, the number of Covid-19 cases is on the rise, but there is no official documentation. In the absence of documentation, the data is inaccurate and the policy decisions made on the basis of such inaccurate data would be fallacious,” said Pratyush Kumar, a practicing physician at Patna and Motihari and a member of the World Organisation of Family Doctors.

A big challenge for the administration, Kumar said, would be scaling up the training for field level health workers and to ensure their safety while carrying out the Covid-19 related works. More clarity is needed on “donning and doffing protocols” as ASHA or ANM workers may not be able to work in a PPE for long hours in summer months. “There are many implementation challenges. For instance, how long would it take to supply the oximeters and RAT kits to field workers. Covid-19 is now being reported from nearly 50% of Indian villages. We need the equipment now,” said Yogesh Jain, a senior physician and member of the Jan Swasthya Sahyog that provides healthcare services in rural Chhattisgarh.

“We can build new hospitals, we can increase beds, oxygenated beds, ICUs and ventilators. But tell me how do I bring in more doctors and nurses,” wondered Maharashtra Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray.

“The government has not done anything in normal times to improve human resources for health in villages. Now it’s a long way to go,” noted Sundararaman.

(With inputs from Rakesh Dixit, Mrityunjay Bose, Tabeenah Anjum and Sanjay Pandey)