At heart, I know that Kumirmari is reducing in size, eroding away part by part. I don’t know what will happen to the Sundarbans in the next 10-20 years,” says Soma Mondal, 30, a resident of the world’s largest delta.

While her relatives have migrated to other parts of India, Soma, married with three kids, stayed on in the Sundarbans. But things have been changing rapidly for her over the last three decades putting her house and livelihood at stake.

Kumirmari is among the last inhabited river islands that border forest islands in the Sundarbans. An embankment fences it on the boundary. At high tide, the island remains eight to 10 feet lower than the flowing river. The village is lower than the forest — visible as a thin line — separating the river and the sky.

This delta is a globally established climate hotspot. Residents who spoke to DH say they have spotted visible changes in regional weather and its effects on their living conditions. The seasonal changes are no longer following a fixed pattern. During high tide, more water flows into the rivers. During storms, which are now more frequent, if an embankment breaks to make way for the salty water, the affected field becomes unfit for farming for the next few cycles.

Subal Barman, a fisherman, is also a witness to silent changes triggered by global warming. “Fish varieties have diminished. It rains abruptly these days, unlike 30 years ago,” he said.

At the School of Oceanographic Studies, Jadavpur University in Kolkata, oceanographer Sugata Hazra has spent years studying the delta. “In the last two decades, we observed that the rate of sea-level rise is the highest in the Sundarbans. The region is witnessing a 5 mm plus rise in sea level annually, higher than the global average. Over 60% of Sundarban coastlines are receding and retreating.”

Also read: Lack of action increases vulnerability

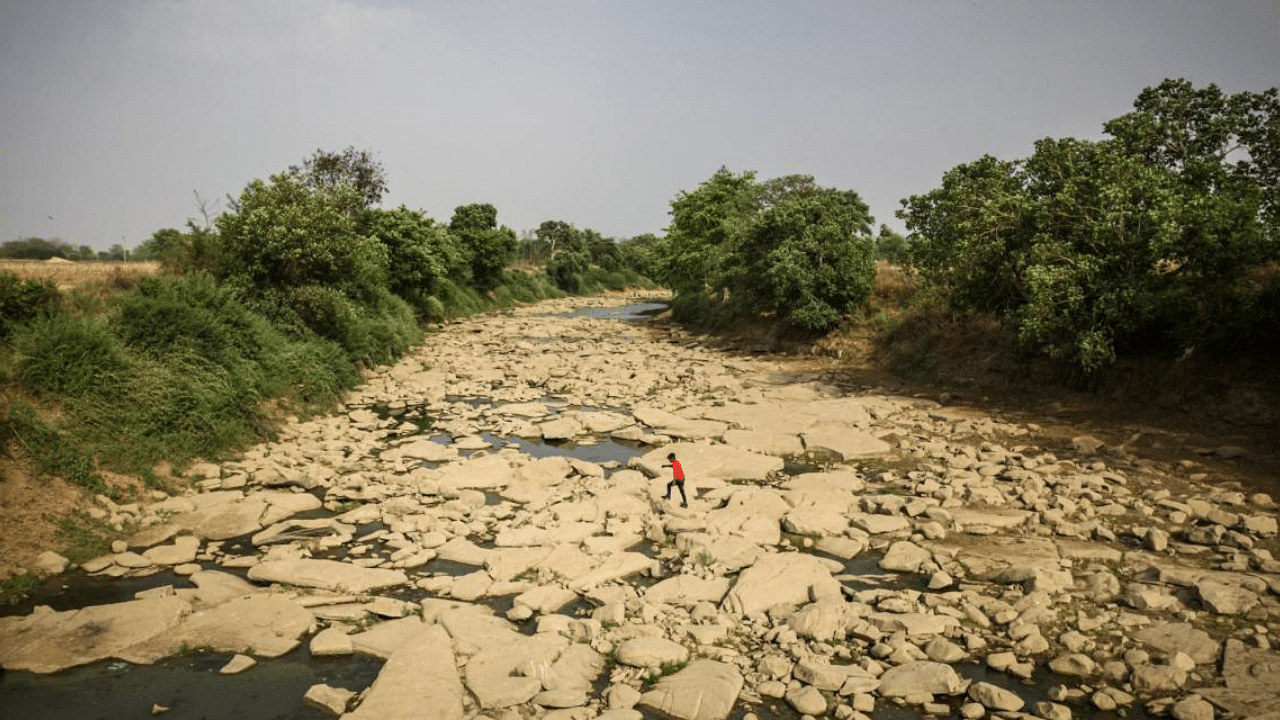

Nearly 1,700 km away at Yadgir, Vishwashankar Shivaray, a farmer at Yelheri village has only one question for the last nine monsoons: to sow or not to sow. In the six of the last nine years, he sustained crop loss. Twice he lost crops due to floods in Krishna river and four times due to severe drought.

“Heavy rains resulted in the loss of topsoil and in the remaining ‘normal rainfall year’ I could not get good yield,” he said. Vishwashankar had to sell five of his 13 acres of land to repay loans he had taken from banks and money lenders.

“I have been fooled four times in the last seven years by the pre-monsoon showers or the ‘halu male’ (spoiler rains). Every time I sowed green gram or groundnut trusting the pre-monsoon showers in May, there has been a deficit rainfall during monsoon resulting in complete damage to the crop,” he said.

Some 250 km away, Abhaykumar Narayan, president of the Grapes Growers’ Association in Vijayapura, has a different story to narrate. April is a peak season for the grape growers of Vijayapura, Bagalkot and Belagavi districts. Farmers take up grafting and pruning the grapevines.

Krishna Raj, a professor at the Institute for Social and Economic Change, who extensively studied agriculture, economics and social aspects of north Karnataka, attributes the crop loss suffered by farmers as a combination of factors including climate change and dwindling forest cover.

It is the same story unfolding everywhere – from the Himalayan states in the north to the plains of south; from industrialised Maharashtra in the west to forest-rich hills and valleys of the North East. Signs of climate change are there for everyone to see.

Himachal Pradesh in 2018 witnessed a major dengue outbreak, which scientists described as a signature of climate change. Because of a change in temperature and rainfall pattern, mosquitoes now breed in the hilly states spreading the vector-borne diseases. Apple orchards are going up as the snowline moves upwards while the famous Assam tea is losing its charm.

Climate change has impacted Assam's tea industry hard. Drought like situation till mid-June in 2021 and excessive rains in May this year has hit production and quality of Assam tea. "Tea needs proper sunlight, rain and humidity. But drastic changes in climate patterns over the years have become a worry. Production was 7% less due to drought-like situations in 2021. This year, it has been affected by excess rainfall," said Bidyananda Barkakoty, advisor of North East Tea Association.

"Our researchers must develop climate resilient tea clones, planting materials or methods of cultivation in order to cope with the climate change impact," Barkakoty told DH.

The UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change last year signaled Code Red in its report that concluded the Earth could warm by 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial temperatures within the next two decades advancing the threat of such a dangerous tipping point in global warming.

The IPCC report says the goal of limiting the temperature rise by no more than 1.5 degrees Celsius by the end of 2100 could be breached between 2021-2040 even if nations meet their current emission reduction targets. The other Paris climate treaty goal of restricting the long term temperature rise within two degrees Celsius may also be breached between 2040 and 2060 in three out of five emission reduction pathways considered by the IPCC, underscoring an urgent need to undertake deep emission cuts.

People bear the brunt

While global actions are mostly stuck on the negotiating tables, people are bearing the brunt. In Tamil Nadu’s Cauvery delta, the state’s rice bowl contributing to 35% of paddy cultivation, unseasonal rainfall and erratic monsoon have added to the woes of the farming community.

“Crops are sensitive to water. They just need the required quantity of water. Less water and excess water are equally dangerous. While less water leads to withering of crops, more water than needed leads to inundation. This is exactly the problem that farmers in Delta are facing today,” ‘Cauvery’ S Dhanapalan, general secretary, Cauvery Farmers Protection Association, said.

“We are in a place where we receive a month’s rainfall or a season’s rainfall in just 24 or 48 hours. This is the biggest problem of unseasonal rainfall and climate change. Where do we store the water? We don’t get a chance to conserve the water as all storage facilities get filled by then. If the rainfall occurs with a gap, we can use them for irrigation as well as store them,” he said.

Climate change is a reality in Kashmir, the paradise on earth, which too is feeling the heat. Electric stores near Dal lake or downtown Srinagar now keep large stocks of ceiling fans, which used to be a rarity till early 1990s.

Kashmir, according to the State Action Plan on Climate Change, witnessed a rise in temperature of 1.45°C over the preceding two decades. It predicted a further 2°C rise in temperature in future. Kashmir’s temperature between 1879 and 1979 had registered an increase of only 0.7°C, but there are signs of rapid changes in recent years.

In 2018, 2019 and 2020, the valley received bountiful snow in winters but the temperature in Srinagar touched 14.2 degrees Celsius against an average of 6.9°C in January. "Climate change is as much a reality in Jammu and Kashmir as it is in other parts of the world. There are numerous signs, such as the extreme intensity and distribution of snow," said Sonam Lotus, director of Meteorological Kashmir.

Drought cycle

Over the last two decades, Maharashtra experienced back-to-back droughts in the Marathwada and Vidarbha region while three cyclones struck Konkan in the last two years. Unseasonal rainfall, hailstorms and severe heat waves that swept the central Indian landscape.

"Of the 36 districts in Maharashtra, 11 were found highly vulnerable to extreme weather events. Droughts and dwindling water security account for 40% of the cropped area across central Maharashtra. In the same way, 37% of the state’s agricultural area spread over 14 districts was moderately vulnerable. This means three-fourths of Maharashtra’s cropped regions are high to moderately vulnerable to the climate crisis," said Chaitanya Adhav, a scientist at Indian Council of Agricultural Research's National Dairy Research Institute, Karnal.

Over the next five decades, annual mean minimum temperatures are expected to rise significantly across 80% of Maharashtra districts.

“Studies have confirmed that warmer climatic conditions never favour farm productivity. The future rise in temperature is very likely to reduce the productivity of traditional rain-fed (jowar, bajra, pulses) crops and irrigated cash crops (sugarcane, onion, maize)," said Rahul Todmal, assistant professor of geography at Vidya Pratishthan ASC College, Baramati, Pune. "It’s time to alter the agricultural practices to tackle the food security challenge."