At a cabinet meeting chaired by Sri Lankan President Gotabhaya Rajapaksa on February 1, Sri Lanka abruptly scrapped the Colombo Port East Container Terminal project with India and Japan, delivering a body blow to Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s much touted ‘Neighbourhood First’ policy that has been unable to forestall the re-entry of China into the Indo-Sri Lankan theatre; or, for that matter, in the rest of the ‘neighbourhood.’

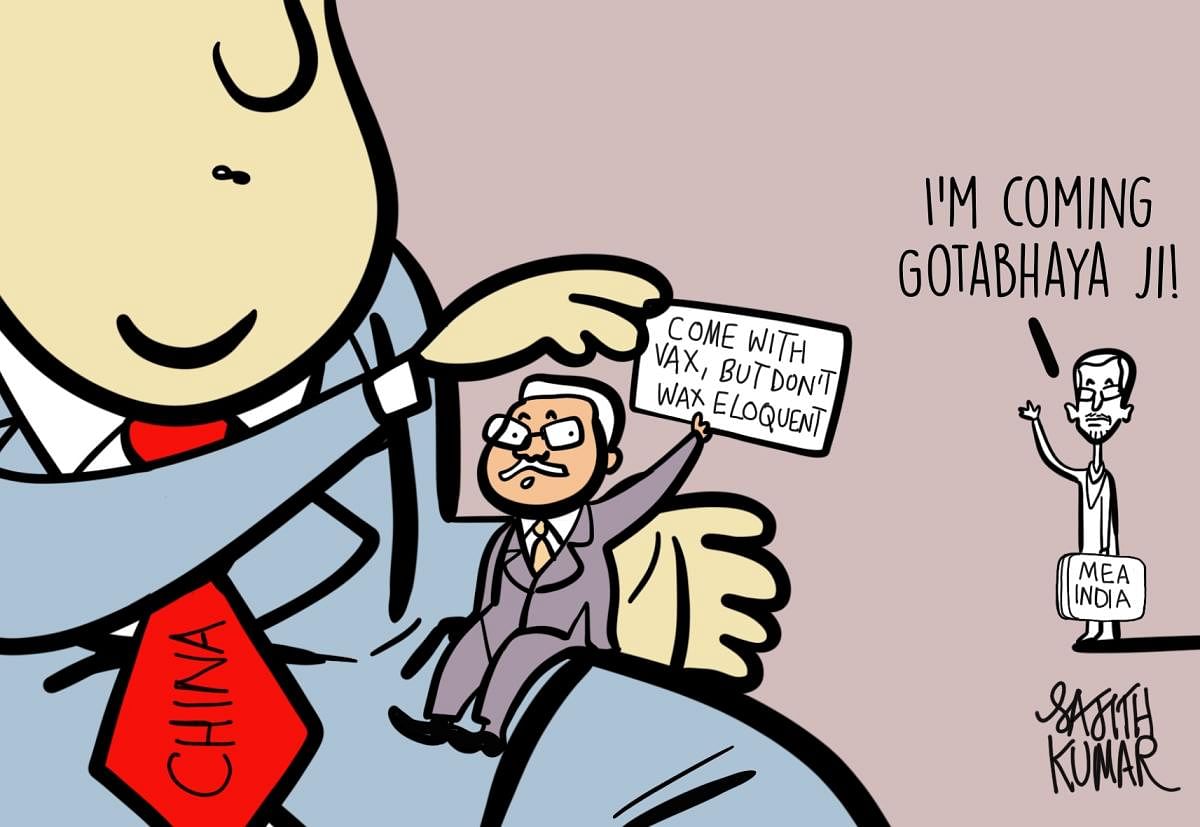

The project was announced by President Gotabhaya himself on January 13 in the presence of India’s External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar, who was visiting Colombo. What changed between January 13 and February 1? And why did India’s foreign policy mandarins not see this coming?

Was it payback by the island-nation’s first family, which India had alienated when it worked behind the scenes to edge Gotabhaya’s brother Mahinda Rajapaksa (who is now Prime Minister) out of the presidential office in 2015? Or was it more than just that? The multiple ramifications of the move go beyond a simple tit-for-tat settling of scores by the Rajapaksas.

With Sri Lanka reeling under an economic downturn, post the Easter bombings and the pandemic, Beijing has gone back to being Colombo’s main benefactor, with the door now open for it to take control of India’s strategic underbelly.

That President Rajapaksa used specious objections by trade unions protesting against handing over the project to foreign interests as the reason for going back on the 2019 deal gives weight to the charge of a Chinese role in scuppering the project, which would have had the much-favoured Adani Group as the major investor in the port development. Currently, more than 80% of the cargo from there is India-bound.

Adding weight to the charge is the fact that China is developing the Colombo International Container Terminal right next door to ECT, and no trade union has raised an objection over it. This, despite the fact that a huge parcel of land, some 50 acres along the harbour in the capital, has become the sole property of Beijing.

As Colombo-based security and geopolitical analyst Asanga Abeyagoonasekera remarked on the Rajapaksa government’s unilateral decision to back out of the ECT citing local protests: “When did geopolitics become the preserve of local trade unionists? When did they start to decide our foreign policy?”

At the same cabinet meeting, Gotabhaya signed off on a Chinese renewable energy project in three islands off the coast of Jaffna, barely 50 km from Rameswaram in Tamil Nadu. This is the third big-ticket Chinese investment, after the Hambantota Port project and the Colombo container terminal.

Hambantota, which had been first offered to India in 2009, was the first move in Beijing’s playbook to use investments to gain a strategic foothold in this critical waterway. (India’s foot-dragging extended to its inability to move forward on upgrading oil tankers leased to the Indian Oil Corporation in 2003 in the deep sea port of Trincomalee, which would have given Delhi a strategic base on the critical north-east coast. Protests by another set of trade unions held that up).

The Modi government’s inexplicable silence over the ECT, even in the face of the consolatory offer of the “larger” West Container Terminal, is in marked contrast to the loud dinner diplomacy that Indian High Commissioner Gopal Baglay indulged in when he took office last year. He hosted Colombo’s power elite to a glittering dinner. On the guest list was the heir to the Mahinda Rajapaksa line, Namal, the prime mover behind greater Chinese investment in Hambantota.

Clearly, Colombo’s march back into Beijing’s embrace is unlikely to change. The docking of Chinese submarines in Sri Lanka in 2014 – during a visit to Colombo by then Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe – had raised concerns in India. Delhi’s worries have only increased with the Chinese presence in Colombo, and now, the three islands of Delft, Analativu and Nainativu.

China will now have the wherewithal to impose a chokehold in the narrow stretch of sea, and block trade and oil supplies, just as India and Vietnam have done in the Malacca Straits and the East China Sea. The islands will become a key listening post from where Beijing can monitor’s India’s southern naval operations all the way from Port Blair in the Andaman & Nicobar islands to Vishakapatnam in the Bay of Bengal to Kochi on the Arabian Sea coast and up to the Pakistani port of Gwadar at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, as part of its strategy to limit India’s remit in these waters.

Limiting India in its sphere of influence in South Asia is clearly a counter to its advance eastward, where India has been a willing partner with the US, Australia and Japan to thwart China as part of the Quad grouping in the Indo-Pacific. The Indian Ocean Region that Delhi has sought to dominate, in tandem with Bangladesh, Myanmar, the Maldives and Sri Lanka, backed by the US to keep Chinese expansionism at bay, is now going to be that much harder to secure. Beijing’s ability to take control of Colombo will not be easy to thwart.

The Rajapaksa government’s intent was evident with its Foreign Minister Dinesh Gunawardena’s quick amending of his ‘India First’ policy to a ‘Sri Lanka First’ policy. Yet, when the Modi government dispatched Jaishankar to the island-nation in January, when President Rajapaksa announced the Colombo Port’s ECT project, he was blind and deaf to the Rajapaksas’ shift.

Insiders say that Jaishankar’s visit to a key Tamil leader, even a moderate like Sampanthan of the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), and openly voicing support for devolution to the provinces, in what was widely seen as a move for the BJP to secure votes in the forthcoming elections in Tamil Nadu, was the proverbial red rag to the Sinhala majoritarian bull. The Rajapaksas had little choice but to move swiftly to appease their Buddhist vote bank, which is raising the false bogey of a return of the LTTE, with the TNA as a front.

Blindsided in Nepal, caught napping by China’s nibbling of border areas in Bhutan, Ladakh and Arunachal, and playing the long game in Myanmar, insiders say that India has had no answer, no forward policy, to thwart China’s mode d’emploi of building infrastructure projects such as ports and roads to gain influence across South Asia.

In a giveaway of China’s real intent, one of the key elements of the Sri Lankan port agreements not only bars all foreign countries from use of their ports, it asks for China to be alerted to all ship movement in and out of Lankan ports.

The changing equations between India and Sri Lanka are set to get a further twist with the arrival in Colombo on February 23 of Pakistan’s PM Imran Khan, one of the first South Asian nations used by China in its signature Belt and Road Initiative.

The timing of Khan’s visit is curious. It comes at a time when the Tamil diaspora has stepped up calls to the United Nations Human Rights Commission to re-open the Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission report that had all but cleared the Mahinda Rajapaksa government of human rights abuses during the 2009 war against the LTTE.

The new report by Michele Bachelet, the UN Commissioner for Human Rights, however, is particularly damning. It states that “in the 12 years since the end of the war, Sri Lanka has failed to demonstrate that it has the political will to move forward on a domestic or a hybrid justice process and reparations for atrocity crimes committed during the war in 2009.”

Bachelet will call for “alternative international options for ensuring justice and reparations, including referral to the International Criminal Court, and restrictions and a travel ban on alleged Sri Lankan war criminals, and stronger presence of the body in Sri Lanka” when the UNHRC convenes later this week.

How Pakistan, a member, like India, votes will separate friend from enemy.

The Rajapaksa government’s worry also stems from the coming together of the Tamils and Muslims (whom they had successfully divided) in the east and the north. In a show of strength, tens of thousands from both communities embarked on a long march from Ampara all the way to Jaffna in the north, a fallout of the crackdown on Muslims post the Easter bombings in April 2019. The government banning burials of Muslim Covid-19 victims has made matters worse. The government’s cancellation of Imran Khan’s address to Parliament has not gone down well, either, especially with leaders like Rauf Hakeem of the Sri Lanka Muslim Congress.

Can India use this tiny window of opportunity, and put aside the hurt and embarrassment of the ECT, and offer to play the role of interlocutor with the Tamil people, with whom it shares a civilisational link that transcends boundaries, and expedite the many stalled projects to rebuild the lives of the Tamils, still reeling from the civil war that ended 12 years ago?

India’s Colombo conundrum could see some light with the appointment of the new Sri Lankan envoy to Delhi, Milinda Moragoda. Having served as one of the government’s main negotiators with the LTTE in 2002 when he was part of former Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe’s team makes him an ideal bridge to the Rajapaksas, though unconfirmed reports that his Sri Lanka Pathfinder Foundation, with close links to China, is a possible beneficiary of the ECT project and BRI largesse can only complicate matters.

If Delhi does not want to see ‘India’s Ocean’ turn into China’s backyard, it needs to step up at multiple levels, not take relations with Sri Lanka for granted.

(The writer was formerly Foreign Editor for the Dubai-based Gulf News and has reported extensively on Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Middle East. She is the author of ‘The Assassination of Rajiv Gandhi’)