On January 1, an estimated 67,385 babies were born in the country. More than 2,000 of them won’t see their first birthday. They are simply unlucky. India is not the best place in the world for a child to be born.

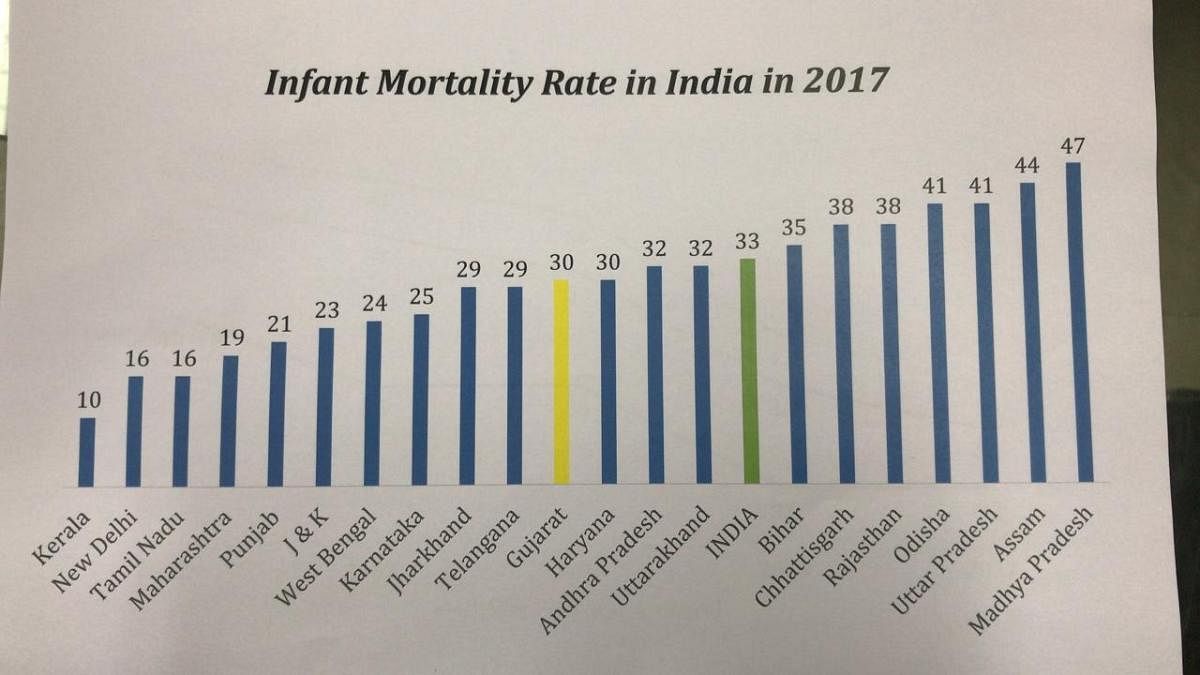

Undoubtedly, there is a marked improvement in the infant mortality rate (IMR) compared to what the situation was two decades ago. The IMR has dropped from 57 in 2005-06 to 41 in 2015-16 and 33 in 2017. The states have done well to bring back the number and the declining trend is likely to continue.

But unfortunately, many of the newborns don’t survive a year or even a day due to health complications as reducing the neonatal mortality remains a challenge. The four big states of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan account for nearly half of neonatal deaths in India, which in turn accounts for 14% of global newborn deaths. Death of more than 100 kids in a hospital in Kota last month once again brought focus on the sorry state of child-care affairs in most of the government hospitals in the country.

“Majority of newborn deaths can be averted by strengthening primary healthcare and implementing low-cost, high-impact interventions including early and exclusive breastfeeding; immediate skin-to-skin contact between the mother and the baby; medicines and essential equipment; and access to clean, well-equipped health facilities staffed by skilled health workers,” said Yasmin Ali Haque, UNICEF representative in India.

Easier said than done, particularly in government hospitals that treat far more number of patients than their capacity and are perennially resource-starved. India currently has 734 district-level government hospitals where the quality of care is under doubt.

“In government hospitals, often the care is desperate as the child is brought in a terrible condition and there is perpetual lack of equipment, manpower and resources,” H P S Sachdeva, a former professor of paediatrics at the Maulana Azad Medical College in Delhi told DH. “To compound the issue, doctors are often transferred.”

A 2016 study on the neonatal ICUs in 52 private and public hospitals in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana showed availability of paediatricians was more in public-funded medical college and private hospitals rather than public-funded hospitals and private medical colleges. The number of nurses was also inadequate.

“Specialist doctors were more commonly available in private than public hospitals, a finding that has also been described in regard to emergency obstetric care in India. Despite this, admission rates are higher in the public sector, which serve low-income groups and can’t refuse admission despite overcrowding,” researchers from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine and Hyderabad unit of Public Health Foundation of India, who carried out the study, reported in the journal PLOS Medicine.

Government doctors said public-funded hospitals functioned under the obligation of not turning away anyone and accepting even those babies who were taken first to a private set-up by his/her parents thereby losing valuable hours and resources.

At times, private hospitals release critical patients once they realise that survival chances are bleak, leaving doctors at the government hospitals to fight a losing battle. In the process, private hospitals can keep their death toll low while most of the blame shifts to the government hospital.

ALSO READ: Where newborns go from cradle to grave

This, however, does not mean that everything is hunky-dory in the government setup. Take the case of J K Lon Hospital.

While a four-member central panel now examines the issues behind such a steep rise, Rajasthan government’s own probe found deficiencies ranging from the shortage of equipment (such as warmers as most deaths were due to hypothermia) and doctors (transferred to a medical college).

“Government hospitals have a demand-supply imbalance that has not been addressed for a long time. It impacts the quality of care,” notes Sachdeva. “We miss independent, strong and effective regulators of the hospitals. Why can’t the city governments put out the number of deaths every month on their website so that everyone knows if there is a spike in neonatal deaths in the winter? Also, the population and district hospital ratio need to be relooked,” said Dileep Mavlankar, director of Indian Institute of Public Health, Gandhinagar.

The 2014 India Newborn Action Plan puts 2030 as the target date to achieve the “single-digit neonatal mortality.” Going by the current trend, it’s a long way to go.