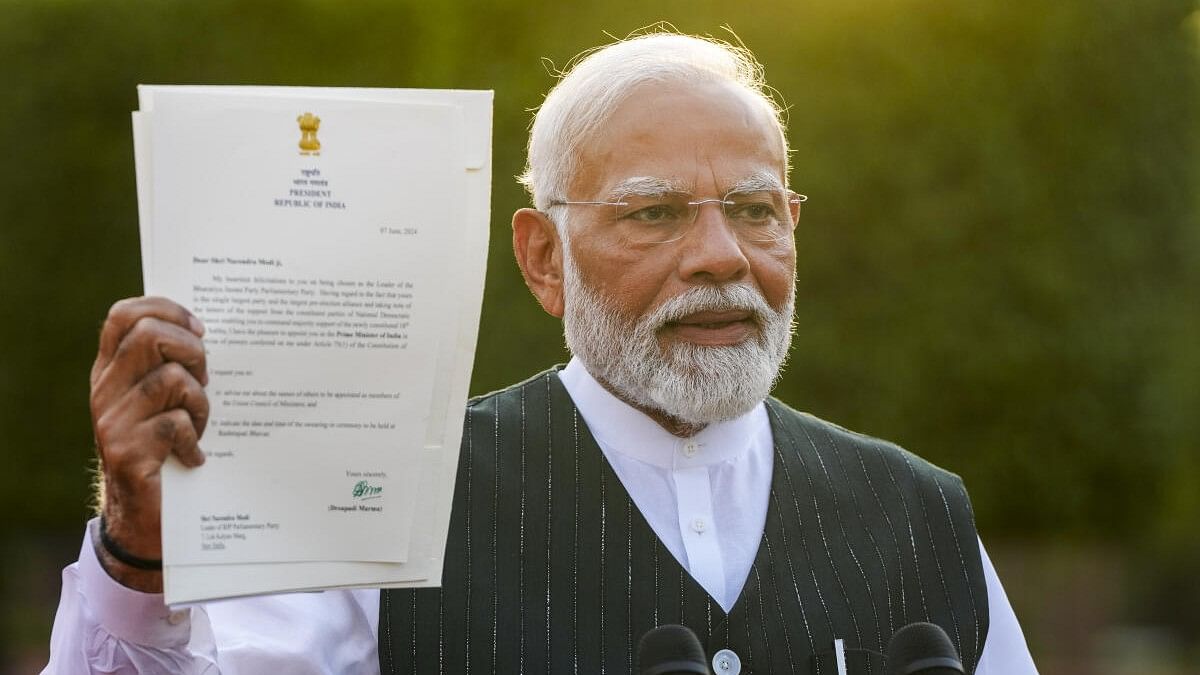

Prime Minister Narendra Modi shows to the media the letter of his appointment as Prime Minister by President Droupadi Murmu

Credit: PTI Photo

Prime Minister Narendra Modi, heading into his third term with a weakened mandate, wants India to embrace a new “green era” at the forefront of climate diplomacy and clean technology.

To succeed, he’ll need to balance those ambitions against a need to sustain growth and satisfy rapidly accelerating electricity demand, leaning on a fraying power system still heavily dependent on coal.

Modi, who has cast himself as climate champion for much of the past decade, will be under pressure to make faster progress toward existing green targets, including pledges to hit net zero by 2070, install a mammoth 500 gigawatts of non-fossil energy by the end of the decade, and corral a global alliance on solar power that aims to secure $1 trillion in investment.

But significant expansion in clean energy — India added over 100 GW of renewable capacity during past 10 years of Modi’s government — has not been enough to satisfy steep demand growth and the limitations of the country’s transmission and distribution networks.

Credit: Bloomberg Photo

With energy security a priority, coal still accounts for roughly three-quarters of output today and its use continues to rise. India plans to add close to 90 GW of coal projects by 2032 — about 63 per cent more than the existing blueprint, published in May 2023.

New Delhi has expanded coal mining to a record, extended the lives of power plants and pressed for the softening of language around fossil fuels at international climate talks. State miner Coal India Ltd., which until the pandemic was planning to diversify into solar power, is now prioritizing the spending of record sums to expand fossil fuel output.

This is unlikely to ease under a new government.

According to Ashwini Swain, fellow at New Delhi-based research organization Sustainable Futures Collaborative, a more fragile and fractious coalition could be prompted to push for projects that spread largesse and earn political support. “Protecting the fossil ecosystem may seem to be aligned with the objective,” he said.

Of course, India’s green ambition is real and the country, among the most climate-vulnerable globally, has been experiencing more frequent instances of extreme heat and drought.

A pro-poor, pro-growth agenda does not need to rely on coal, which has shown itself to be costlier and less reliable than cleaner alternatives, said independent power analyst Alexander Rutter, who is based in Bengaluru. “There is a real opportunity for the new government to radically rethink its strategy by doubling down on renewable energy and storage rather than on investments in new, uneconomic and unreliable coal plants,” he said.

But the investment requirements are steep, especially when it comes to infrastructure changes that will underpin a transition, from overhauling mobility in sprawling cities to power networks. In 2022, India’s electricity planners calculated that in order to reach India’s renewable goals, the cost of laying new cables alone would be around 2.4 trillion rupees ($29 billion).

Renewable projects are still often built in barren areas, far from demand centers in cities and industrial hubs, where the power is consumed.

Meanwhile, the fragile financial health of distribution companies connecting homes or factories regularly deprive them of reliable supplies. A 3-trillion rupee project led by the power ministry will go some way to fixing profitability, thanks to initiatives like smart metering, but progress is slow.

Credit: Bloomberg Photo

One potential change for the next five years will be the role of local parties, which may ease centralization and bring regional interests up the agenda, climate analysts and researchers said — and that includes spreading green manufacturing and clean energy benefits.

“A coalition government should allow more states to make claims on the growing green economy in India,” said Rohit Chandra, assistant professor at the IIT Delhi School of Public Policy. “The last decade saw most of this activity in four or five states, including Gujarat and Rajasthan.”

Those two states — also bastions of support for Modi’s party — do enjoy the lowest cost of energy generation, but poorer regions will now have a greater political role, potentially pulling investments to less affluent areas.

“If we see more decentralization and more state-led growth, you could see some of these transition policies being intertwined with bread and butter economic aspirations, including health and education,” said Shayak Sengupta, energy and climate fellow with the Climate at Observer Research Foundation America.