Ships and aircraft of the Indian Navy (IN) and aircraft of the Indian Air Force (IAF) exercised with the USS Ronald Reagan Carrier Strike Group in a combined exercise off Thiruvananthapuram on June 23/24. A press release issued by the Press Information Bureau appeared to suggest, however, that the exercise was between the IAF and the US Navy; IN’s participation didn’t figure in it. In the ensuing online discussions, the inadequacy of inter-service command and coordination structures came to the fore. Such disconnects between the military services are bad enough for public relations, but they can have devastating implications in war.

On July 2, another online interaction with the CDS and the Chief of Air Staff (CAS) over the impending Military Theatre Commands saw perceptional differences between the Services emerge. These public debates reveal seams in inter-service collaboration and coordination that have long existed.

When the Kargil War took place between India and Pakistan in May-July 1999, for instance, after initial Pakistani intrusions were reported, the Indian Army launched Operation Vijay to evict the intruders. The IAF would launch a separate operation code-named Safed Sagar to flush out regular and irregular troops of the Pakistani Army. Military forces ideally need to approach such operations jointly than as separate operations as effective command and control is crucial.

The Kargil Review Committee (KRC) reviewed the nation’s security and intelligence systems and made significant recommendations for the future. A Group of Ministers (GoM) subsequently conducted a comprehensive review of the entire security apparatus using specialist task forces. The reports led to far-reaching changes in the security and defence apparatus.

While most recommendations of the KRC got implemented through the years, the creation of the CDS and Vice Chief of Defence Staff (VCDS) had remained pending for various reasons till 2020. The Narendra Modi government appointed Gen Bipin Rawat as CDS on January 1, 2020, overcoming the lack of a political consensus and decades of internal dissent within the military services, spurred by, among other things, the 73-day standoff between Chinese and Indian soldiers at Doklam in 2017 and continuing border skirmishes and other ominous signals from China.

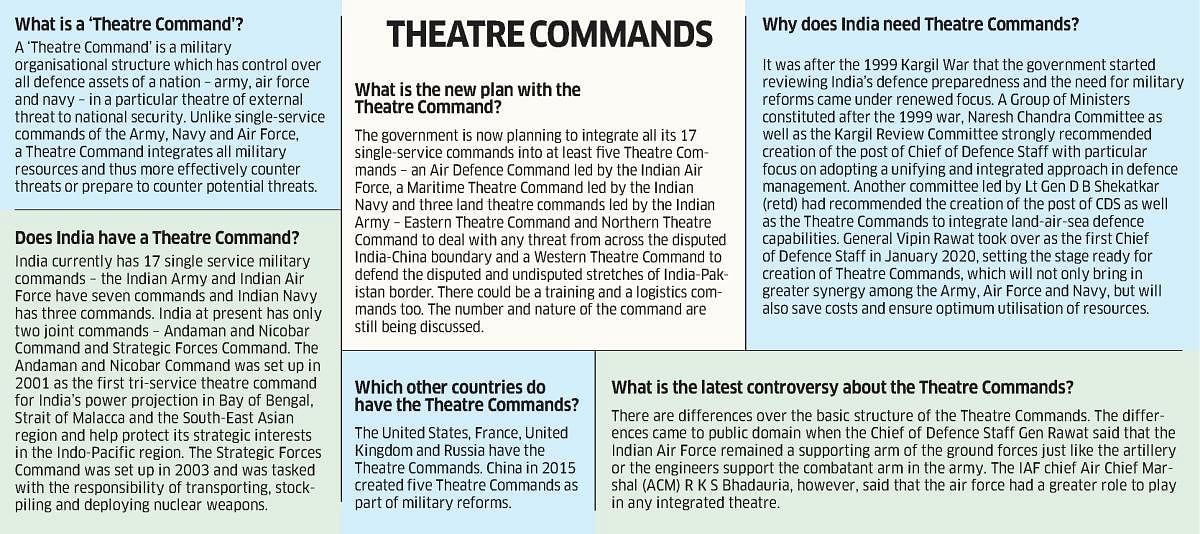

With the CDS in place (while the vital appointment of a counterbalancing VCDS remains to be made), the government seeks to further the integration of individual service commands of the Army, Navy and Air Force into unified or theatre commands to bring about joint planning and warfighting. The CDS is mandated to evolve the plan for the transformed military structure within his three-year tenure. Half that time has already elapsed, and it seems the chiefs cannot agree on what that structure should be and how to shape it.

Theatre Commands

Currently, the Indian military forces are organised under 17 Service-specific commands, with some of the commands of the different Services overlapping (in presence) in their areas of responsibility, yet with neither their headquarters co-located nor operating jointly on shared tasks. Even where the commands are embedded in one another physically, decisions on missions and allocation of assets and resources are still controlled by Service headquarters, a sub-optimal situation.

Theatre Commands are meant to bring all three Services together under a single commander for the ‘theatre’. The ‘theatre’ itself can be geographic – say, tasked to take on China on the northern border, or Pakistan on the western border; or they can be functional – an air defence command tasked with defending the airspace of the entire country, or a maritime command to take care of maritime security on both seaboards of peninsular India.

The efforts at merging the multiple command headquarters of the three arms of the Indian military into joint organisations such as the proposed Maritime or Air Defence Command seek to enforce ‘proactive jointness’ – the ability to achieve effective cooperation before going into battle. The idea is to be able to bring to bear on the enemy the land, air and sea-based capabilities of the Indian military together or in combinations in any battle. That said, views about jointness, as may be put forth by one Service, can be anathema to another. Such ideas have plagued every effort at integration and jointness the world over.

Modern militaries must contend with an unprecedented ability of diverse forces to transmit, receive, and disrupt vast amounts of data. Such factors’ influence headquarters organisations and decision support processes as commanders seek to apply art and science to understand the situation, plan, and execute at the ‘speed of relevance’.

While each military arm has risen to the occasion, evolving networks and communications, systems or protocols that integrate on an all-Service basis remain elusive. Each Service needs to overcome stove-piped organisations. Proprietary information silos that bind legacy single Service headquarters have no place in the modern battlefield.

In 2021, institutionally ingrained, conventional mindsets will need to change as the ‘Revolution in Military Affairs’ continues with the rapid march of technology. Transformation is not about sacrificing single-Service ways and means for other Services’ ways and means. It is about synergising them into a meaningful whole. We only need to look across our borders to the east, where the Chinese People’s Liberation Army has been at it since 2012, modernising rapidly under the watchful eye of Xi Jinping, to understand the modern military transformation imperatives.

Military Leadership’s Responsibility

With the political nod having been given and the institution of CDS a reality, effective implementation and transformation are now the responsibility of the military leadership. The political executive will need to ensure that single-Service parochialism on this occasion cannot thwart jointness.

The first Commander-in-Chief of the Andaman and Nicobar Command, Admiral Arun Prakash, has pointed to how the ANC was part of a larger plan to enhance military integration and encourage ‘jointmanship’ – the training and ability of all three Services and their soldiers to fight together. He has noted that the ANC was not envisaged as a pure fighting formation but as a ‘crucible of a concept’. Despite such efforts, lip service to jointness and parochialism (a natural attribute of bureaucracies, including military bureaucracies) holds sway. It’s this that plagues Indian efforts towards jointness to this day.

The government may need to bring in lateral inductees into the Department of Military Affairs (DMA) if senior military leadership cannot rise to the occasion. Cultural barriers to transformation cannot hold up urgently needed reforms.

Laterally inducted from his post as Chairman of Hewlett-Packard, David Packard helped US military reforms as he pushed the ordinary, influencing people and endeavours positively. The 1985-1986 Packard Blue Ribbon Commission on Defense Management played a significant role in the eventual implementation of the Goldwater-Nichols Department of Defense Reorganization Act of October 1986.

Traditional approaches to command and control are not up to the challenge. Simply stated, they lack the agility required in the 21st century. Reforming Indian military organisational structures is unavoidable. India needs to look ahead and create a military organisation for what can be turbulent decades ahead.

(The author is a former Flag Officer Naval Aviation, Chief of Staff Headquarters Andaman & Nicobar Command and Chief Instructor (Navy) at the Defence Services Staff College, Wellington)