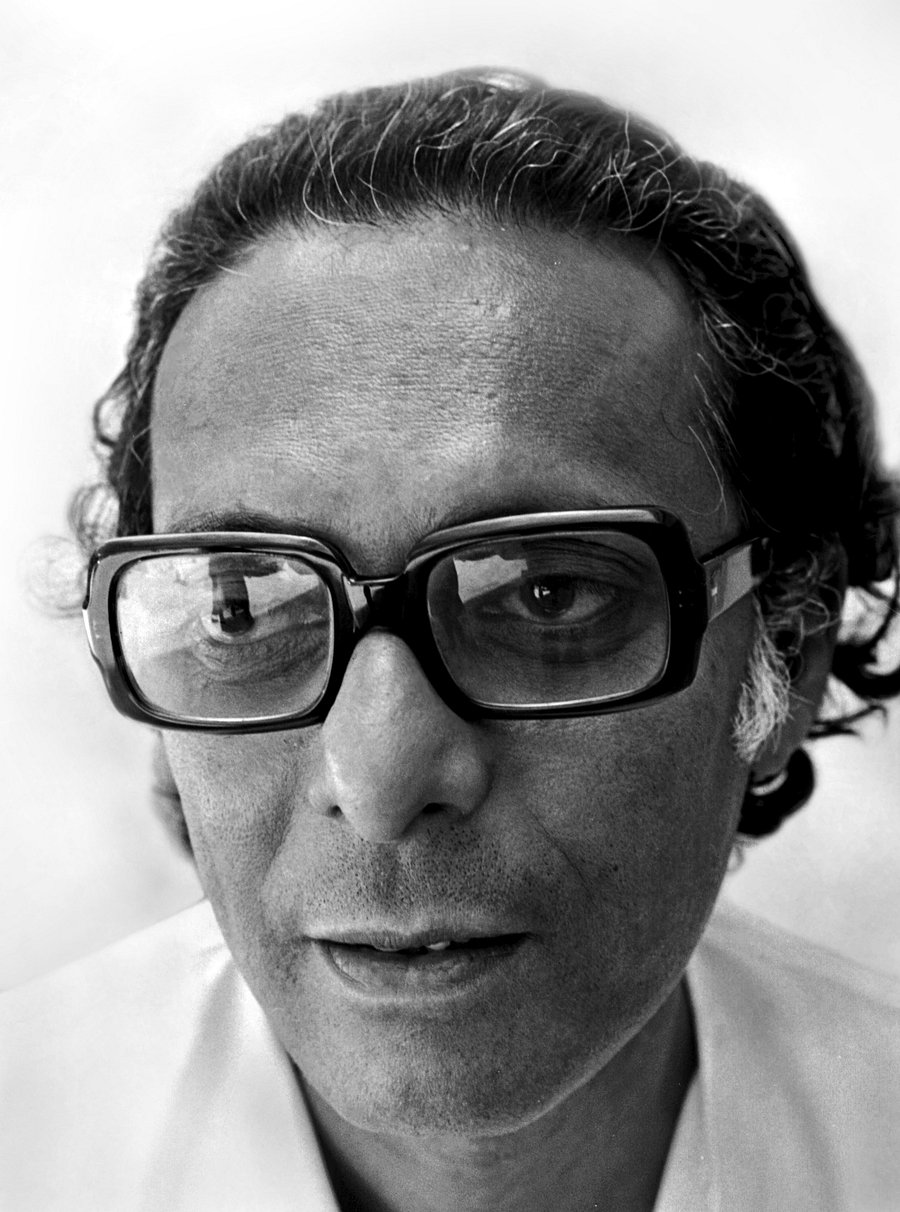

CINEMA, like any other art-form, can only help in creating a climate which leads to social, political and moral awareness, said Mrinal Sen, who recently won the Soviet award for outstanding artistes in an interview.

What do you have to say about Indian cinema ( of course, looking back over a period of 32 years)?

Mrinal Sen: As I am with a borrowed typewriter ready to answer your questions, I have in front of me a young man who is just 32 and is in films suffering from despair and yet not leaving cinema in the hope that around the corner there is something he is looking for. Yes, indeed, this is what is Indian cinema today. A vast lot of films are being produced every year, the number of productions is increasing rapidly, both in Hindi and in other regional languages, the costs mounting at a very rapid pace, austere productions in B & W are being quickly replaced by expensive colour stuff, but looking critically at the end- products, most of such annual output is seen to be no better than rubbish. All this is disheartening.

But what my 32-year young friend is looking hopefully for is a new awareness which is seen to be manifesting itself through the untiring efforts of a handful of young and veteran filmmakers operating their brains wonderfully well in various regions of the country.

As an incorrigible optimist I have every reason to convince myself and others that Indian cinema, even though it is now being ruined by the headless monstrosity, will gradually be looking sane and healthy, The history of Indian cinema has to follow the same logic which determines the growth and development of cinema in other countries. So, go on hoping against all hopes, suffer temporary setbacks, but never plunge yourself in total despair.

BATTLE

What I see in Indian cinema is a persistent battle which the discriminating few have been wagging on all fronts – production and distribution. What it needs most is to find parallel exhibition channels. And all this is no easy task.

Some of us feel there is a crisis in Indian cinema… do you think this feeling is justified?

Ans: We are sleeping with crises- financial, ideological and moral. And all this quite often threatens us with physical extinction. And, believe me, I am not dramatizing our case. Since we cannot escape the crises, the point is to face them and not indulge in sustained despair.

Do you seriously believe your films can “change” the Indian reality? Can you give any instances of films “changing” reality? (Indian or foreign).

Can you mention one single work of literature which has “changed” the reality of a particular society? I am pretty sure you cannot. Can you think of any musical composition- of Beethoven or of Mozart or of Schubert or of Tchaikovosky- which has acted as what you may call detonator in a society? I know for certain, you cannot.

How then do you expect cinema to do the impossible? Cinema is no magic wand nor is it “the barrel of a gun”-So, be patient and desist from practising romantic obsession. Cinema, like any other art-form, can just help in creating a certain climate which leads to social, political and moral awareness. And that is all: and that, indeed, is great.

About my films, well, I can very modestly cite examples evidencing certain emotional kicks or jolts which my spectators had suffered as they watched my films.

There is a charge against the “art” film makers – that they are alienated. And it is this “alienation” which makes them seek refuge in protest films. Your comments:

Ans: Would then conclude that “art” films and “protest” films are all alike? Any film worth its salt claiming to project the reality of a class-divided exploitation -based society has got to be, in the fitness of things, somewhat of a protest film. Whether the protest will be loud or mild, oblique or direct, subtle or blatant is the film-maker’s choice. Not certainly alienation, it is involvement which provokes you to protest against badly organized state of things in the society.

I do not know how you would define define “art” film. Any film worthy of being called a film is an aesthetic experience and aesthetic exercise. But, then, there are various ways of defining and of looking at aesthetics.

Do you consider yourself a “committed” filmmaker? Tell us about transferring your commitment on to the celluloid.

Ans: Referring to the Polish filmmaker Zanussi you once said that his choice was so definite as to make him committed. If this is your definition of commitment, which I wholeheartedly endorse, I consider myself committed.

FAITH

My ways of transferring my faith or commitment are different in different situations. At times, depending on particular situations, I am not ashamed of indulging even in over-reaction. Are you shocked?

How do you view your own films now? Do you see any growth/ any change – have you moved away from (say) Bhuvan Shome? If yes, why?

Time is changing. Cinema’s vocabulary is changing very fast. So, as one bound by time and my medium, I cannot but change. In other words, I feel I am growing and, in the process, correcting my own conclusions.

Bhuvan Shome was made in 1969 and so in 10 years I have travelled a long way.

Tell us about your latest film.

Ans: My latest film – a kind of fiction- documentary combine- called PARASHURAM, depicts life on the city pavements. The pavement dwellers are mostly rural migrants who once were landless farmers and who are now reduced to the level of the sub-proletariat community. The leading character, not by any chance my protagonist, once killed a tiger with him axe while felling trees in a jungle. It was just on an impulse that he killed the tiger. But, as everybody knows, Parashuram’s crusade against the Kshatriya’s was an act of retribution. My job in the film was not to look for the militants among the rural migrants. It was just to make a few valid socio- economic points and, in the process, to be critical of the soul-killing system prevalent in our society and also to develop respect for the circumstances in which my characters live and perish.

In a way, the film also tries to portray the concept of an average man who, suffering humiliations all his life, indulges in pitifully impotent fantasies. I wanted the film to be funny and grim.

Your reaction to criticism of your films- how does it affect you?

As everybody does, I react quite favourably to kind words and make frantic efforts to ignore unkind comments which, unfortunately, I cannot forget.

Has any critic managed to make you change your views?

No, unless my wife and son talk sensibly to me.