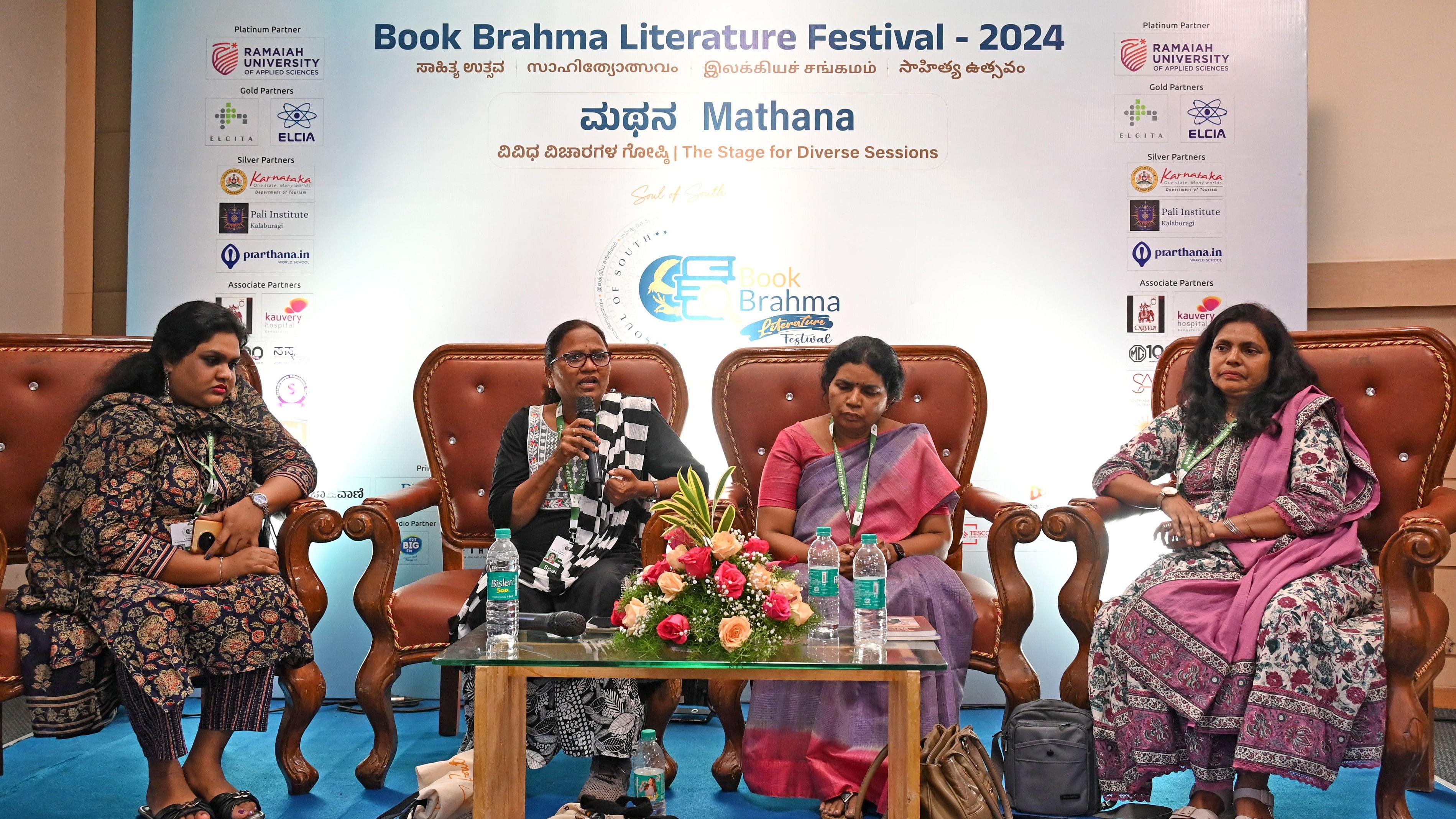

(L-R) Manasa Yendluri, Joopaka Subadra, Challapalli Swaroopa Rani and M M Vinodini during a session on 'From Feminism to Dalit Feminism' at the Book Brahma Literature Festival 2024 in Bengaluru.

Credit: DH Photo/ Pushkar V

Bengaluru: What is popular as the feminist movement today is not inclusive of voices from the Dalit, Adivasi and minority communities, believe Dalit writers and activists Challapalli Swaroopa Rani and Joopaka Subhadra.

They spoke to DH at the Book Brahma Literature Festival 2024 in a short interview about what it is like to be Dalit women writers today.

Subhadra believes the popular notions of feminist movements in the country today are a western, white-washed borrowing. "Feminism in India today is dumped from foreign countries. It serves Savarna women who are inside four walls of a home, who are different from Dalit women. We are in society, sweeping in public, doing labour so the question of feminism and its discourse is not the same and its scope is limited," she says.

While patriarchy and gender discrimination affects everyone, it affects women of different castes differently, she noted, this impacting Dalit feminism differently. "Upper-caste men control land, politics, powers, industries, literature. So we are all – Dalit women and men, Advasi women and men, Bahujan men and women – fighting against this male chauvinism," she adds.

According to Rani, more and more educated second- and third-generation Dalit women are wishing to not identify themselves as Dalits and are distancing themselves from the identity.

"This is because, after having some exposure to education and financial betterment, they go close to upper-caste (people) and their mindset becomes similar. They don’t want to call themselves Dalit and their writing is not so powerful because they don’t experience the kind of pain that first-generation people do," she says.

The pain she referred to is a result of societal discrimination and segregation arising out of casteism which, in her opinion, is absent in younger generation Dalit writers whose writing is not strong due to a lack of lived experience.

Additionally, Rani observed that second and third generation Dalit writers also shy away from responding to Dalit issues in educational institutions, social forums, and public spaces.

"They hide themselves, just stand aside and watch. They do not join in protests, do not stand together. However, though first generation writers are not direct victims sometimes, they go close to the victims and stand with them," she noted with dismay, urging Dalit writers to give up on their hypocrisy to fight the many forms of caste discrimination.