When Pranav, an avid trekker, went to Kodachadri with his friends for a weekend getaway, he found the place to be a clean, serene and welcoming mountain peak.

However, when he revisited the trail a few years later, he got lost in the forest. The only way he could find his way back to the city was by following a trail of plastic bags.

He recalls, “The good thing was that I found my way out but the bad side was that the trail was filled with litter and plastic. This is why I decided to promote the message of eco-friendly travel and tourism after I started my company ‘Madventures’.”

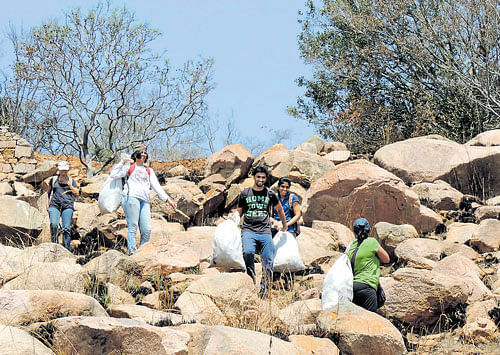

At ‘Madventures’, Pranav chooses a few volunteers to pick up trash like plastic bags, paper, chips packets and glass bottles on every trek.

He is not alone. With Bengaluru becoming a home for trekking groups and travel organisations, companies are strictly seeing to it that keeping the surroundings tidy is their responsibility. Virender Sirohi, founder of the Bangalore Trekking Club, says, “With more and more routes being discovered in and around the city, it’s important to see that trekkers and travellers maintain offbeat areas as they are and not turn them into commercial hubs.” He adds that trekkers generally carry different bags for collecting garbage on the trek and help segregate the waste in the process. “So we have bags for glass bottles, paper, chips packets and plastic. Juice packets are also some of the most common items we find. We come back and give it to the various recycling units in the city so that their task becomes much easier. Trekkers are realising the importance of this now. During a trek, there really is nobody to keep a check on the cleanliness of the hill or the peak. While the BBMP takes care of it in the city, the regular maintenance of the hill becomes the trekker’s responsibility more or less.”

Apart from cleanup drives on treks, they have regular events in the city as well.

‘Get Beyond Limits’, another outdoor company, also has two policies to keep their surroundings clean — ‘Project Green’ and ‘Leave No Trace’ policy. Salwat Hamra, the founder, says, “These policies have been in place ever since we started our company. According to us, they mean giving back to nature. We use bags to clean up the place and come back and dump the garbage in dustbins. We have tried using jute and cloth bags but they don’t hold that much weight and eventually break. We are still looking for a replacement.”

According to him, nature itself inspires a trekker to contribute back. “It is a challenge, of course, and quite a repetitive process. The hill may not stay clean for long. A lot of people do come back and dump garbage in the same hill once we finish cleaning it and this is something we have no control over. We look at it as an organisation’s responsibility and do our bit to keep the place free of garbage.”

While permissions are not really a problem here, Virender says that a few forest departments do require permissions when a group is going only for a cleanup drive.

“We initially found it difficult to convince the forest department of Chikkaballapur and Doddaballapura when we wanted to clean up Skandagiri and Makalidurga. They were skeptical initially and let only 30 of us clean the hill. But later, once they got to know the kind of work that we did earlier, it was fine.”

He adds, “Such cleanup drives make a slight difference because future trekkers may feel that they shouldn’t litter a place that is already clean. However, the bigger change has to take place at the policy level so that an effective system will be in place.”