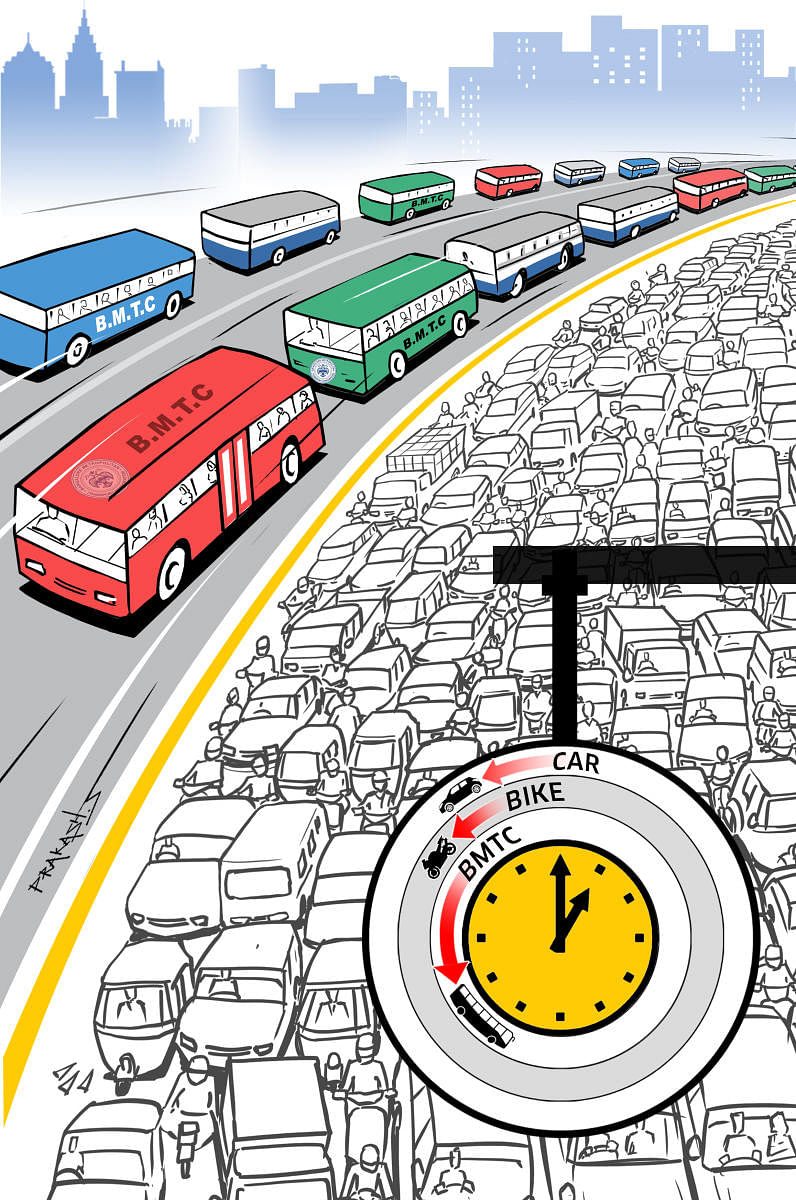

Boost, upgrade, speed up public transport, and watch people shift to it in droves. For decades, this strategy, articulated by every sustainable mobility expert, remained just a talking point. Can the now-functional Bus Priority Lane (BPL) on Outer Ring Road (ORR) finally spark a dramatic shift in policy?

The first signs are promising. Bus commute gets 16 minutes faster than before, screamed a survey report, weeks after the BPL got operationalised between Silk Board Junction and K R Puram along the ORR.

A commuter survey by Citizens for Bengaluru (CfB) told a story that was even more specific: That the number of people who spend over two hours on daily bus commute has reduced by a substantial 62% post the BPL introduction. This is a sureshot message to build on the BPL, scale up.

Challenges, formidable

But challenges, big and small, remain formidable: Poor lane enforcement, traffic indiscipline, inadequate signages, parking chaos and the sheer number of private vehicles. Without a major shift from private to the public BMTC buses, evening peak hours are still where they were: Notoriously chaotic.

The CfB report clearly saw the loopholes. Seventy-five per cent of the commuters who responded to the survey were convinced that the visual signages had to be improved. Indicating a big hole in enforcement, 81.1% said they did not spot any traffic police to control buses at the designated stops. An even higher 83.8% did not see a single Sarathi vehicle tasked with assisting buses align smoothly to the BPL.

The survey, conducted from November 19 to 23, had the authorities thinking. By November 30, the Bengaluru Traffic Police were on the Road, imposing penalties on motorists who forayed into the BPL lane. A notification issued a fortnight before had clearly stipulated which vehicles were allowed: Only BMTC buses and emergency vans.

Penalty starts kicking

The fortnight gap, as the police explained, was to ensure that the public were well aware of the lanes. Hundreds have already been booked for straying into the priority lane. Under ‘other offences’ of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988, the first offenders were asked to fork out Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 for every subsequent violation.

But multiple issues still remain unresolved. How do private vehicles enter and exit service lanes that lie beyond the BPL designated on the extreme left of the main road? Since these are not clearly demarcated, cars and two-wheelers will cross the BPL and run the risk of getting penalized. Is there a way out?

Flexible barriers

There is no clarity yet on the barriers. Should flexible bollards be used or would demarcating lines on the road surface suffice? Will physical barriers dissuade motorists from changing lanes, or will it lead to more congestion?

A reality check aboard a BMTC bus from Marathahalli to K R Puram shows just why the barrier problem is complex. Bus driver Mallikarjuna Swamy draws attention to the roadside tree branches jutting out, and says: “To avoid hitting them, we have to often stray away from the lane. Barriers may not work always.”

Since the BPL is still in its infancy, several cabs, vans and trucks could be seen parked right in the middle of the lane. Swamy notes, “It is tough to stick to the lane when this happens. During peak hours, it gets even worse. We have no other go but to get to the next lane.”

Enforcement gaps

To streamline the BPL system and signal other vehicles to stay away from the lane, the police had posted its personnel at many bus stops along the ORR. But during the reality check, only two personnel could be seen doing their duty. The rest were seated, even as the bus passed by.

Spearheading a campaign to make the ORR BPL a success, Srinivas Alavilli from CfB emphasises the need for a tech-driven awareness campaign. “A mass outreach, on the lines of the health hazards of smoking, is required. That is why we organised the NimBus Yatra,” he says.

BMTC, he notes, has already boosted their daily revenue from the BPL stretch by Rs 3 lakh. “That is a very good beginning.”

Corporates, incentivise

But to help thousands of IT employees on the stretch to make that big switch from cars and bikes to the BMTC buses, the corporate tech parks have to take the lead, says Alavilli. “They should incentivise employees taking the bus, and disincentivise those taking private vehicles. Let them start charging for parking inside. You need both push and pull to make the BPL a success.”

In the BPL, Tara Krishnaswamy, another key member of CfB, finds the public interest finally growing in public transport. “People are now asking for more deployment. For the first time, there is an understanding of public transport. This is a shift from flyovers and signal-free corridors that benefit only private vehicles,” she elaborates.

E-surveillance

For the ORR project to be fully successful, she suggests a mix of e-surveillance and hefty penalties to dissaude motorists from entering the BPL. “Combine this with good signages both on the road and on boards, and aggressive public campaigns. Traffic police too should improve enforcement. They should pull up their socks.”

The success or failure of the ORR pilot will define whether the system could be extended to other arterial roads of the city. The Bruhath Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) has proposed a stretch from Goraguntepalya on Tumakuru Road to Nayandahalli Junction on Mysuru Road to demarcate a dedicate lane.

Also on the Palike’s agenda are BPL lanes on Old Airport Road, Hosur Road and nine other corridors with high traffic density. To scale up the system, BBMP is now in talks with the other stakeholders, the Bangalore Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC), the traffic police and the Directorate of Urban Land Transport (DULT).