Building violations in Bengaluru

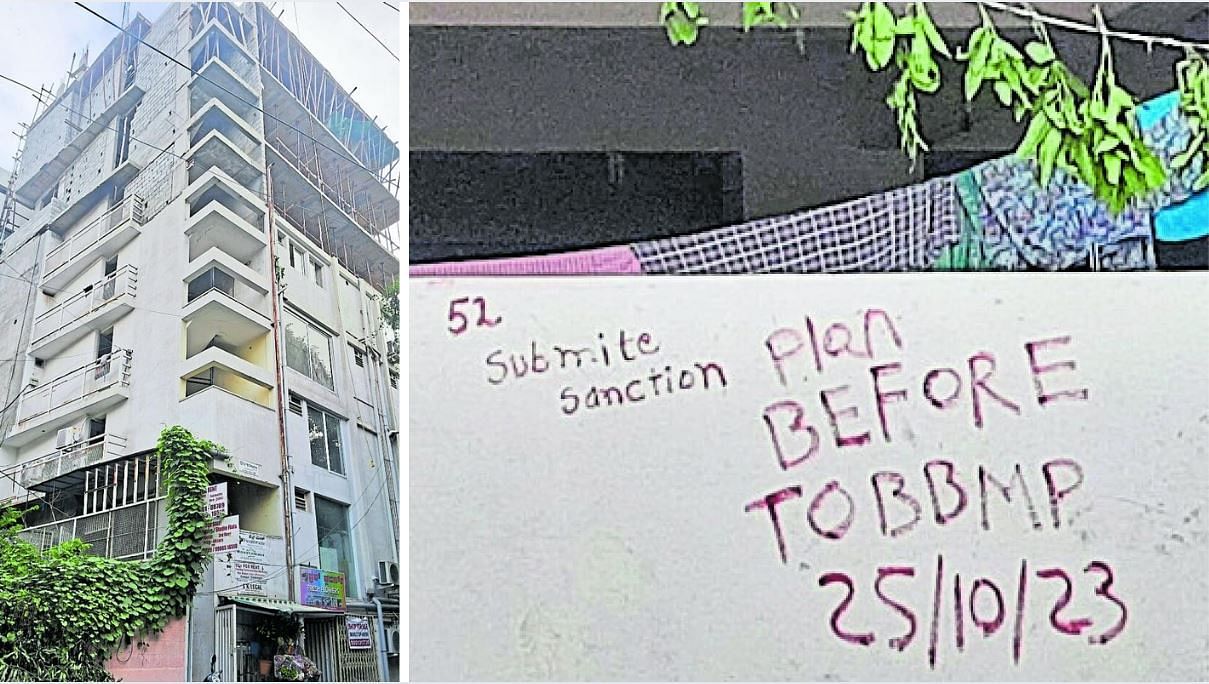

Photos shared by DH readers

On April 24, six months before the illegal building in Babusapalya near Horamavu in Bengaluru collapsed, the BBMP issued the first notice to the building owner, seeking “information” about the illegal construction instead of immediately stopping the work.

There was neither a response from the builder nor any communication from the civic body until September 21. Almost a month later, the six-storeyed building collapsed like a pack of cards, killing around nine workers on the spot.

Illegal constructions are not new to Bengaluru. At least one building in every street deviates from the sanctioned plans by throwing norms such as ground coverage ratio, floor area ratio, building heights, and setbacks to the winds. While the BBMP allows deviations of up to 5%, there is no instance of demolition even when the building deviation exceeds 50% and reaches even 300%.

Last year, the BBMP devised a 117-day action plan to tackle illegal construction in the zones. The task was divided between assistant engineers, assistant directors of town planning, and joint commissioners. The zonal commissioner was recently empowered to handle complaints about unauthorised construction. None of the BBMP’s actions has reached a logical conclusion: demolition of the building.

In most cases, the BBMP will not act against an illegal construction when there is no citizen complaint. As per the rules, the civic body is expected to act within 117 days, including demolishing unauthorised structures. Sometimes, the matter gets stalled in the appellate

authority or city civil courts even though these legal entities do not have the jurisdiction to admit appeals against demolition notices.

The High Court has been the only major source of justice for people fighting against illegal constructions, provided the neighbourhood is willing to shell out a minimum of Rs 50,000 or Rs 1 lakh for legal fees.

How do illegalities continue?

Som Thomas, a resident of Cooke Town, shared many instances where the BBMP itself admitted illegal constructions as far back as February, March, and April of this year. “We could ensure the work in one of the buildings stops as the immediate neighbours approached the court. Work on the remaining six buildings continues in full swing even now. The BBMP has taken no action on the ground except issuing three notices,” he said.

Suhas Ananth Rajkumar , a resident of CV Raman Nagar, says there are three laws to deal with illegality: the BBMP building bylaws, the Revised Master Plan 2015, and the BBMP Act of 2020. “I realised how each of these is circumvented easily in my fight against illegal buildings,” he says. He identifies many loopholes that help BBMP to turn a blind eye to illegalities.

While applying for a sanctioned plan, one must have a registered architect who will sign and say she will ensure the building is built according to the plan. These architects usually conspicuously resign before the construction starts, and no new architect is appointed. The rules do not have a provision to stop firing this architect, nor do they mandate hiring a new one.

Every builder must request BBMP town planning officials to inspect and give a Commencement Certificate (CC) when the work starts. This can help identify some deviations, such as setback violations in the beginning itself. However, no punishment is mandated for any builder if he does not apply for CC.

No order issued by the chief commissioner of BBMP specifies any punishment for any official who fails to identify illegal buildings. Enquiries are conducted, but documents often mysteriously disappear.

Before December 2020, one had the provision to appeal at the Karnataka Appellate Tribunal (KAT), formed under the Karnataka Municipality Act. Builders colluded there with lawyers, and the case was usually dismissed. In some cases, KAT repeatedly adjourned cases, dragging them for years.

When the BBMP Act came into force, Suhas alleges that many documents were backdated to bring the issue under the KMC Act. Under this Act, when assistant engineers served notices, giving a copy to executive engineers was not mandatory. Many such notices were served by hand, not post, to avoid a timestamp.

Suhas gives an instance of backdating the order. “In an illegality case where I went to court, the assistant executive engineer of the ward backdated the notices and inspection with fake measurements and said there were no illegalities noted at that time. She showed 55% violations as 2.5%. This was ridiculous because there were no extra floors at that time. The court said these are minimum violations and let it continue. Today, the building has been occupied, and people are living there, he explains.

“Later, a TVCC investigation found falsifying of the document. The official who did it had got promoted,” he adds. He narrates another case where officials falsified documents and got Occupancy Certificates for a building. “Those living there are under the impression that it is 100% legal,” he adds.

Unless BBMP takes stern action on the violators without fear or favour, the illegalities are bound to continue, feel citizens.