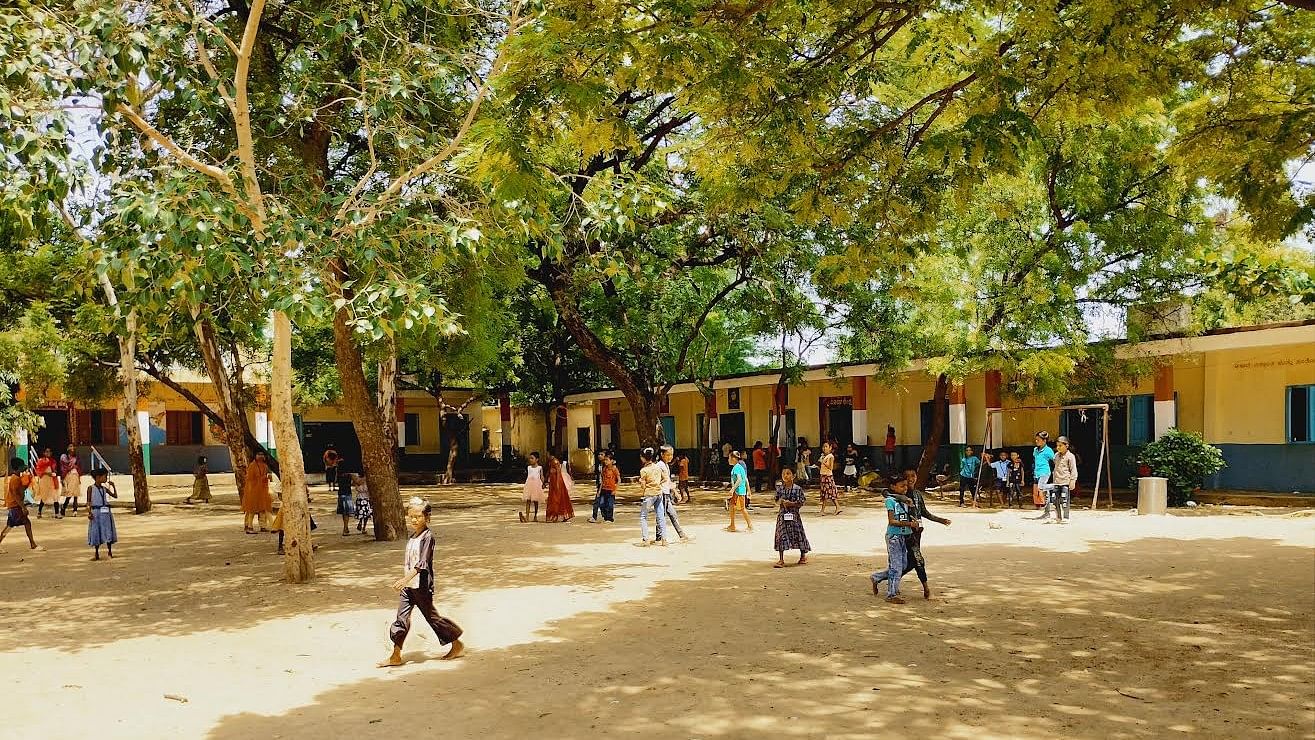

A Kannada medium school at RH-3 camp near Sindhanur. Nearly 80% of students here are Bengali-speaking Hindus.

Credit: DH Photo/Pavan Kumar H

Refugees fleeing religious persecution in Bangladesh are yet to find a footing in their settlements near Sindhanur town in Raichur district.

There are 15,937 refugees in four rehabilitation (RH) camps here. Over 40 per cent of the Bengali-speaking Hindus in these camps do not have citizenship though they were rehabilitated five decades ago. Those who have been allotted land are unable to access it due to the lack of proper mapping.

Seventy-one-year-old Sunil Mestri, for instance, still remembers the challenges his family of 12 had to face while escaping the Pakistani army and the religious fanatics in 1970 in East Pakistan. His family had left behind 30 acres of land, cattle and savings in Khulna in Bangladesh after communal riots broke out.

Three months after staying in refugee camps across India, they were rehabilitated in one of the four Bengali camps in Sindhanur taluk. A total of 1,000 families with approximately 6,500 members were given shelter here.

While Mestri is an Indian citizen now, his 11-year-old grandson is not. The reason — Mestri's daughter-in-law Chandana is registered as an 'unauthorised' settler in India even though she has lived in India for over 40 years. "My daughter-in-law's family entered India during the peak of tension in Bangladesh. As they crossed the border without proper documents, she has been branded unauthorised," says Mestri.

Chandana has an Aadhaar card and a ration card, but her name is not included in the voters' list. She has not been able to provide her parents' documents. Even though her son was born in the Sindhanur government hospital, he is not considered a citizen of India.

Nearly 40 per cent of the 16,000 residents in the four camps do not have Indian citizenship despite having lived here for 40-45 years, says advocate Pranab Bala, an office-bearer of the primary agriculture credit cooperative society of the camp. "The worst affected are women, who have come to the camps after marriage," says Bala.

Meera Malti, who came to RH-3 camp after marriage, says that in Kolkata, they didn't have to produce any documents to get benefits. "Here, I am facing problems as my parents do not have proper linking documents."

Officials cite rules while expressing their helplessness. "All those who can provide linking documents are getting citizenship. We have received roughly 800 applications out of which only 220 were eligible," tahsildar Arun Desai said. He clarified that having an Aadhaar or ration card does not make refugees eligible for citizenship.

Not just citizenship, the residents of the settlement are unable to avail government benefits. While the Indira Gandhi government had provided them nearly five acres of land, an 80*50 plot and two cattle to make a living at the camps, they are unable to 'officially' claim this land even today due to an issue with the survey numbers.

Subrath Kumar Das, a beneficiary, says the family has been struggling to get mutation of the five acres of land as the administration does not have proper survey numbers.

Deputy Commissioner Chandra Shekar Nayak said these issues have emerged due to errors committed in the initial days of settlement. "There are no proper records regarding the allocation of land; beneficiaries are cultivating on lands allocated to someone else."

Residents of the camps also complain that while their relatives in other parts of the country are eligible for reservations under Scheduled Caste categories, they have not been so fortunate. The Karnataka government has not recognised the Namasudra community, to which the majority of the refugees belong, as SC/ST.

Ashok Lambani, a government teacher at RH-3 camp, where nearly 80 per cent of students speak Bengali, says, "A majority of the students are missing out on higher education due to a lack of reservation and finances."