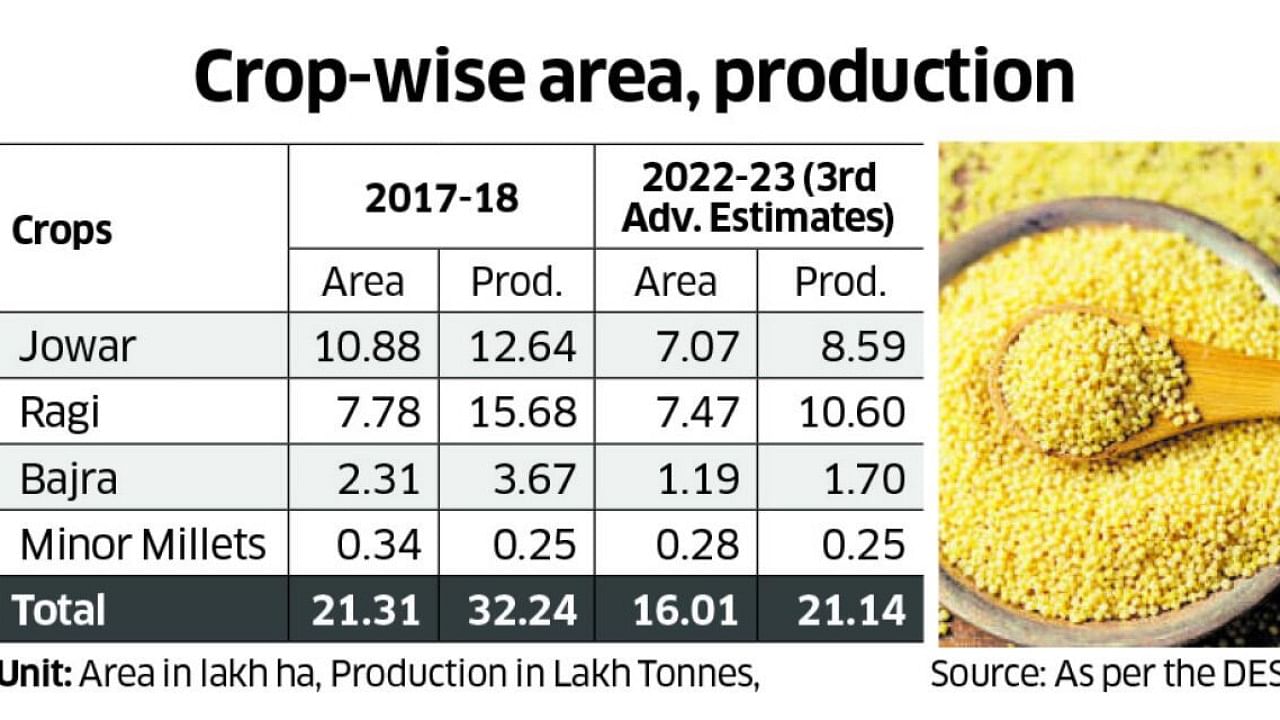

Notwithstanding the steady rise in demand, the area under millet cultivation in the state has decreased over the years. Data accessed by DH from the Agriculture Department shows that the area under millet cultivation has declined from 21 lakh ha in 2017-18 to 16 lakh ha in 2022-23.

Correspondingly, production has come down from 32 lakh tonnes to 21 lakh tonnes during this period. The decline is driven by jowar, the area under which has decreased by over three lakh hectares in the last five years.

Inadequate government intervention for procurement and distribution of certain millet varieties, lack of processing and marketing facilities, lack of stable prices and non-availability of required machinery are discouraging farmers from taking up millet cultivation.

Also Read | Chief of UN farm fund lauds India for reviving global focus on millets, exporting wheat to 18 countries

Ragi, jowar and bajra are the three main millet crops grown in the state. The rest of the millets- foxtail, little millet, kodo, browntop, proso and barnyard - are categorised as minor millets and the area under their cultivation is 0.28 lakh ha.

“Farmers are shifting from jowar to maize and cotton due to yield gap and a lack of technological intervention,” says Prakash Kammardi, former chairman of Karnataka Agricultural Prices Commission. While a farmer gets 18-20 quintals of maize per acre, jowar yield is 6-7 quintals an acre.

“There is a provision under the food security act to bring all millets under the public distribution system (PDS), which the government has not effectively implemented,” Prakash says.

Ragi is an exception. “Minimum support price and an efficient procurement process under PDS have encouraged farmers to continue growing ragi,” says researcher and activist V Gayathri. However, farmers who have taken land on lease are not considered under the minimum support price scheme.

Lack of processing units and marketing avenues has forced millet growers to sell their produce at a throwaway price. “The area under millet cultivation is reduced by 5 per cent in our area,” says Tipperudraiah B, who represents a millet farmers’ producer organisation in Sira taluk of Tumakuru district. Gayathri also says that there has been little research on millet varieties aiming at better yield and standardisation of cultivation methods.

Manual harvesting is another problem that millet farmers face. “The available machinery can’t meet the requirements of small landholders who form the majority of millet growers,” says Chandrakant Sangur of Bhoosiri Millet Farmer Producer Company in Haveri. In Raichur, farmers are switching from bajra to tur dar as the pulse fetches good prices at local procurement centres while bajra does not have a procurement centre.

M N Dinesha Kumar, who has been working towards reviving millets, has observed that the initial enthusiasm has not stayed in farmers due to multiple factors like the lack of decentralised processing units and stable prices. “While there is a growing awareness about millets in urban consumers, the current supply is meeting only 10 per cent of the demand. Consequently, the prices are also prohibitive,” he says.

As we celebrate the ‘International Year of Millets’, there is great potential to increase demand. We can match the demand only with comprehensive policy and research on scaling up millet production, he says.

While acknowledging that millet growers have been switching to more remunerative crops, G T Putra, Director, the Department of Agriculture, says that the government has been supporting millet growers at different levels. “We have supported over one lakh farmers to grow minor millets under the Raitha Siri scheme. Also, we have provided financial assistance to eight entrepreneurs to set up processing units,” he says.