Kuvempu is an iconic figure in the tradition of rationality, critical thinking and scientific temper in modern Kannada culture. Throughout his extraordinary career as a poet, novelist, dramatist and essayist, Kuvempu remained unflinching in his bold criticism of narrow sectarian beliefs, irrational superstitious practices and blind, unquestioning slavery to authority of every kind. The sources of his rationalism are not European ideas of enlightenment, which were introduced to the Indian elite through English education. It has more to do with the rationalism advocated by Vivekananda in his critique of the religious priest class and the superstitious practices and rituals of contemporary Hinduism. Like Vivekananda, Kuvempu believed in the universal ideas which imbued the Upanishads and opposed the varna and jati systems. Kuvempu was free from the orientalist binary categorisation of a materialist West and a spiritual East, a problematic element in Vivekananda’s thought.

Kuvempu was a believer in science and was an avid reader of books on astrophysics. In a famous poem, he describes science as a torch or lamp and commends Galileo for constructing an empirical scientific explanation for the solar system as opposed to what the church believed in.

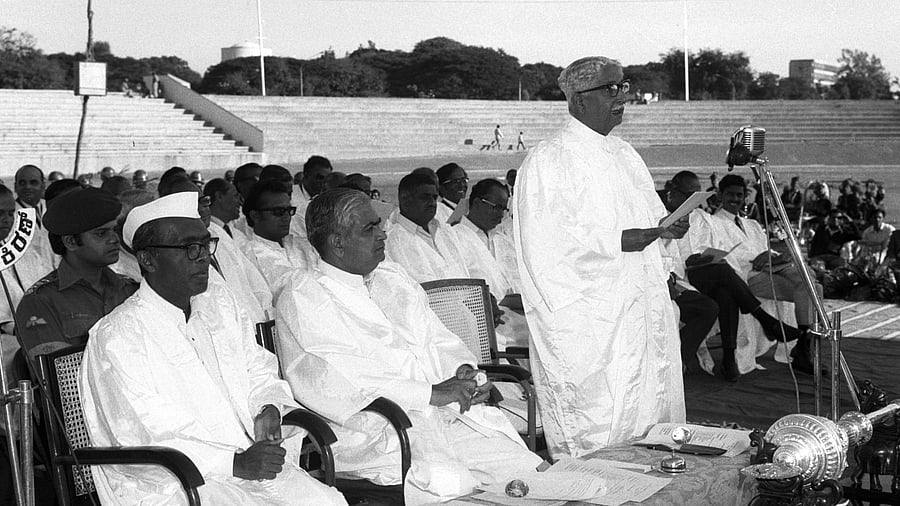

In 1974, Kuvempu gave two speeches which reiterated his rationalist attitude to religion and his critical engagement with contemporary social issues. The first one was his inaugural speech at the historic conference of the Karnataka Barahagarara Mattu Kalavidara Okkuta, an association of progressive writers deeply influenced by Lohiate socialism and the anti-caste movements. Later, this grew into the Bandaya Sahitya Sanghatane, an association of rebel writers. Kuvempu addressed some of his major concerns in his speech and also admonished writers not to be swayed by the uncritical blanket rejection of everything.

Need for reinterpretation

While he agreed with the writers that the literary and cultural texts of the past were problematic, he urged them against a wholesale rejection of the past works. Just as one does not throw away gold ornaments just because they are old heirlooms of the past, but they are smelted to make ornaments suiting the present taste, texts of the past cannot be thrown away. Epics like Ramayana and Mahabharatha need to be reinterpreted and freshly transcreated by eschewing those elements which are obnoxious to the rational mind. Wholesale rejection on the basis of ideologically unacceptable elements, accusing them of being instruments of “intellectual domination” is not reasonable. Writers should use their discretion in avoiding extreme points of view.

His argument is that the priest class is minuscule, but becomes hegemonic because others give their consent to its ideologies. No rebellion can, therefore, succeed unless writers aim at educating and transforming the minds of those who willingly accept the hegemony which enslaves them. He uses an extraordinary analogy, saying that when you shoot a tiger you need a double-barrel gun and a sharp aim. In this case, the gun has to be trained at your head and your brain to cleanse them of blind beliefs and uncritical thinking.

Kuvempu refers to the famous ‘Boosa episode’, triggered by the statement made by Basavalingappa, a minister in Devaraj Urs cabinet saying that much of Kannada literature was mere cattle feed or fodder. The protest against his remarks turned violent. Kuvempu argues that a major portion of all literary traditions in the world is worthless cattle feed. Truly great works are always small in number. He argues that Basavalingappa was evaluating Kannada literary tradition on the criterion of representation of the Dalit experience or perspective. He agrees that mainstream Kannada literary tradition has not provided space for Dalit expression. Kuvempu warns Kannada writers against parochialism and localism. Kannada consciousness should expand itself to include the universal.

In the convocation address delivered at Bangalore University, Kuvempu mourns the sad demise of the Gandhian principles which we had used during the freedom struggle but with freedom abandoned. He says that the Nehruvian economy aspired to imitate that of the developed western countries and ignored the actual status of the Indian economy, impoverished by colonial rule. This led to greater inequality and destruction of the rural economy.

The hegemony of the corrupt political class and bureaucracy and centralisation of power created a political class of ‘scoundrels and criminals’ (Kuvempu’s words) who vitiated the democratic electoral processes, thus killing the true spirit of democracy. Therefore, democracy has become a mockery in India with its history of autocratic rulers and compliant subjects. Returning to his concept of ‘matha’ (sectarian thinking), he says that unless we free ourselves from matha, which consents to innumerable hierarchies of varna, caste and class, there is no possibility of true democracy. Prophetically, Kuvempu also predicts that these anomalies in our democratic system and practices could usher in an ‘electoral autocracy’.

The major interventions made by Kuvempu in defence of a rational critical temperament have greatly impacted generations of writers, activists and especially youth. The anti-caste, pro-Dalit movements in Karnataka have acknowledged the legacy of the vachanakaras of the 12th century and Kuvempu.

Every resistance or movement begins with the iconic poems of Kuvempu. He is probably the only major Kannada writer who is claimed as a mentor by movements as diverse as the Dalit, Bandaya and left-leaning democratic movements. His speeches, interviews and conversations continue to invigorate myriad collective initiatives against communalism, regressive traditionalism and obscurantism. The later generations have been rediscovering Kuvempu through the writings of Prof M D Nanjundaswamy, P Lankesh and Poornachandra Tejaswi.

Kuvempu is a contemporary, a mentor and an intellectual comrade to the youth of the present generation. And also probably the one trustworthy guide amid the present collective frenzy and the destruction of the idea of a pluralist India.

(Rajendra Chenni is a literary critic based in Shivamogga.)