It was a long walk through a hilly landscape mottled with green where bristly bushes wormed their way between brown boulders. There was nary a soul in sight but every so often, the clear sound of a goatherd calling to a stray member of his herd came wafting through the air, followed sometimes by a line of goats crossing our path, nosing and grazing their way through the scrub. It was an idyllic scene and I was almost loath to reach our destination. Almost, but not quite, for at our destination lay one of the country’s oldest written records.

We were in Palkigundu, near the town of Koppal, on the trail of an inscription of Emperor Ashoka, one of the world’s most remarkable rulers.

Despite the arrows painted on some rocks that pointed out the way, it took a few wrong turns, some backtracking, and the help of a goatherd, before we finally stood at the base of two huge boulders, the pair topped with a flat-shaped rock forming a canopy over both. It was this rock canopy that had given rise to the name Palkigundu, meaning palanquin rock, for the two boulders bore the rock canopy like a palanquin. Steep, roughly-laid steps led us to the top of the pair of boulders, and then at last, we stood in front of a message that had been incised onto the rock some time in 258 BC.

The inscription itself was barely visible and it took us a few moments to distinguish it from the natural patterns in the rock. Gazing at the 2,300-year-old writing, I thought about how quite possibly, people elsewhere might at that very moment be reading the same message of peace that I was, for the exact same edict is found in 17 places in India. In fact, the most recent one was discovered just a year ago. Earlier in the day, we had been to see the closest of these other sites, which is actually just 2.5 km away from Palkigundu, east of Koppal, at Gavimath.

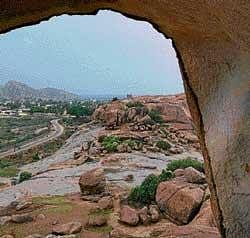

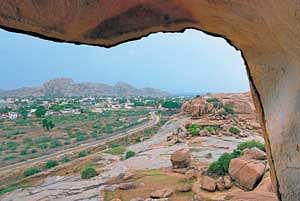

At Gavimath, near Palkigundu

Like at Palkigundu, the Gavimath edict is also situated high on a boulder. And though the inscription itself is open to the elements, this edict too has a sheltered space nearby with a rock canopy chiselled out over it. Historians believe both Gavimath and Palkigundu were used by Jain monks to meditate. I could understand their partiality to the sites, for both locations were quiet and incredibly peaceful nooks with mesmerising views of the countryside.

Like most Ashokan inscriptions, the two Koppal edicts are in the Prakrit language but use the ancient stick-men like script called Brahmi. Some inscriptions in the northwest of the subcontinent are in Kharoshti, and there is even a bilingual inscription in Aramaic and Greek near Kandahar in Afghanistan.

Apart from being able to recognise precisely three letters of the Brahmi script, I could claim no knowledge of either Prakrit or Brahmi, so I was pleased to see that halfway up the short climb to the Gavimath inscription, a Kannada translation of the edict had been painted onto a rock. In place of the usual panegyric epigraphs that most other kings in history have left behind, in the Koppal edicts, Ashoka speaks to us of how he had been a worshipper for two-and-a-half years but had not been very zealous. But in the one year that he had been ardent, ‘gods and men mingled’, he says.

And this can happen when people, whether exalted or lowly, are zealous, he adds. The simple, unpretentious sentences and the direct manner of speech made it seem like Ashoka might have dictated his thoughts to a scribe just yesterday.

Other Ashokan relics and dhamma

Other Ashokan inscriptions on pillars and rocks all over the subcontinent speak of dhamma, non-violence, obedience to parents, the virtues of honesty, and so on. One also speaks of Ashoka’s remorse over the Kalinga war, and how he abjured conquest by war in favour of conquest by dhamma. And in another, Ashoka talks about why he had all these inscriptions engraved: so that people may follow dhamma for as long as the sun and moon endure.

But the reality was that Ashoka and his teachings on dhamma were both forgotten within a few hundred years of his death. When Prakrit, the lingua franca of Mauryan times, was replaced by other languages all over the country, Ashokan inscriptions became indecipherable and the unique story of the king who espoused peace and renounced war was forgotten.

It took the interest of the indefatigable English historian James Prinsep to bring Ashoka back into the national consciousness. Prinsep laboured over the inscriptions in the 1830s, long before the bilingual Aramaic-Greek inscription was found near Kandahar.

When he finally succeeded in deciphering the script, it was a major breakthrough. But it led to another puzzle, for no-one knew who the king referred to in the inscriptions as Devanam Piyadasi (Beloved of the Gods) actually was. It took the discovery of a reference in a Sri Lankan text to an Indian king named Ashoka who was also called Piyadasi, to clear up the confusion.

The real clincher: Maski edict

The real clincher, though, came in 1915 when an edict was found in Maski, in Raichur district, 120 kilometres away from Koppal. This edict is a version of those found in Koppal but differs from them in one crucial aspect: it mentions King Ashoka by name.

The Maski edict finally laid to rest any lingering doubts on the identity of the emperor who had left his signature almost all over the country.

Karnataka is particularly rich in Ashokan inscriptions, having eight sites with Ashokan edicts and a ninth that has edicts as well as other Ashokan-period relics. Today, all these sites are under the care of the Archaeological Survey of India.