On how Dakla descended and dissolved like salt into my being” — so begins writer and activist K B Siddaiah’s foreword to his epic poem, ‘Daklakatha Devikavya’. Gathered for a reading of their play, based on the poem, the cast and crew reflect on the depth of meaning behind these words. For several hours, they discuss the writer’s poetry, the realities that have inspired it, and how these stories can be brought to life.

The team of nearly ten finds that the text transforms and grows with time. Their own interpretations, expressions and insights too, begin to evolve in the process.

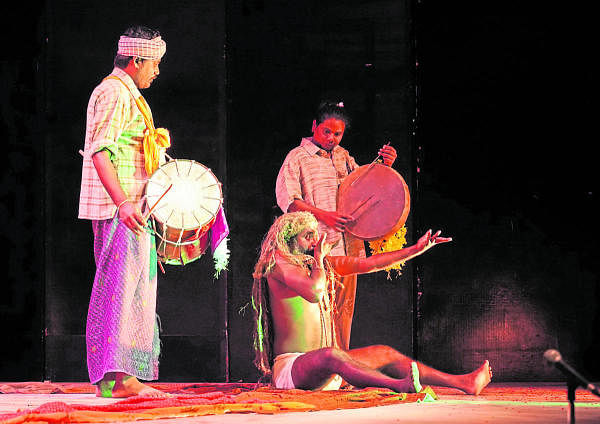

Later, translated onto the stage, these scenes evoke tears, thoughts and even laughter from the audience. With the sounds of the traditional Dalit folk instruments, the areye and the tamte, and the recreation of Dalit rituals and experiences, the performance stands as a challenge — to traditional mindsets, boundaries and the definitions of aesthetics in theatre.

The play, ‘Daklakatha Devikavya’, draws from the epic poem of the same name as well as other stories of writer and activist K B Siddaiah. It presents the inner workings and external experiences of the Daklas — a Dalit community. The poem explores the idea of what makes us ‘human’.

The theatrical representation of Siddaiah’s poetry evokes reflections, re-evaluations and new perspectives from viewers across the state. The complexity of the text and the range of insights the play offers have appealed to audiences of various ages and social backgrounds.

Thus far, 15 shows of the ‘Daklakatha Devikavya’ play have been staged across Karnataka and at Adishakti in Pondicherry. The show is set to be staged at the International Theatre Festival of Kerala this month. A recording of the performance at Ranga Shankara in Bengaluru will also soon be screened on OTT platforms.

Such is the power of K B Siddaiah’s written word, says the play’s director, Lakshmana K P, “I had heard his ‘horaata haadu’ and read his prose. However, it was at the time of his death that I saw hundreds of people gathered together, singing and reciting his poems.” It was then that he began to read Siddaiah’s epic poetry.

“The process of converting this poem into a play was challenging, as it lacked the theatre language,” explains Lakshmana. The text itself is hard to read and understand, and the context is region-specific, he adds. Yet, over the course of their discussions, the team began to think of new ideas and symbols to represent the essence of the poem.

While the Dakla community was new to him, the attitudes and corresponding behaviours of the privileged castes were entirely familiar, says actor Santosh D D, who has been working to mobilise his community to stand up to oppression. “Stories like this haunt me. I have lived through untouchability like this,” he says.

A similar understanding among the actors and musicians yielded rich and impassioned discussions, and eventually, performances. “I did not know about the Daklas, and I was surprised that there was a caste hierarchy within oppressed communities too” says Bindu Raxidi, one of the actors.

“The community’s struggles for food and identity really touched me,” she adds. Bindu cites a scene from the play that moved her— where a Dakla family comes to the Madiga keri to ask for food. The Madigas, themselves marginalised by other communities, consider Daklas ‘untouchable’. So, the family spreads out a cloth, onto which the food is put. They then draw the cloth away, collect the food and return to their neighbourhood to feed their families. The scene is a representation of a common practice in villages where the Dakla community resides.

Transcending limits

The play’s interpretation of Siddaiah’s words has transcended the limitations that literary critics have imposed on the poet, says V L Narasimha Murthy, a lecturer from Bengaluru who watched the performance. “While Siddaiah is considered a poet writing on a spiritual quest, this has been seen as being at odds with modernity. However, the play has gone beyond that to represent equality and raise important questions,” he says.

The lecturer also highlights that the drama addresses intersectionality, by commenting on gender inequality within the caste hierarchy, as well as the practice of untouchability within an oppressed caste community.

One of the elements of the performance that retains and emphasises the spiritual richness of the Dakla community is the music. Unique and central to both the play and the community it represents, the sounds of the areye and the tamte, resound alongside the scenes of the play. Commonly played by the Madiga and Holeya communities, these instruments are also central to the rituals of the Daklas. In bringing both instruments together, there is a harmony that is evident, symbolic of social harmony, says Santosh.

For Narasimharaju B K, the musician who plays the areye, the instrument represents the sound of the hunger that marginalised communities are forced to live in. “We start playing the areye out of hunger. It has fed me over the years, and helped pay for my education,” he says.

Bringing the areye to the stage, a mainstream platform and wider audiences was a new idea for many. People wondered whether the loud folk instrument would suit the theatre performance.

Narasimharaju explains that, as a result of its importance in the Dalit experience, the instrument itself becomes a character. It was in the process of understanding this, that his own perspectives shifted. “Being from the Holeya community, I have seen the Daklas since childhood. But it was only now that I realised that while we speak so much of our oppression, when it came to the Daklas, we become the oppressors,” he reflects.

However, just as change is not limited to the cast, the impact and storytelling are not limited to the Daklas, emphasises Lakshmana. “The play is not about the Dakla community. It is a Dalit epic,” he says. The performances are not an attempt to ‘help’ or ‘mainstream’ a community. Instead, they present a call to be inspired by the cultural heritage, stories and wisdom of Dalit communities, he explains.