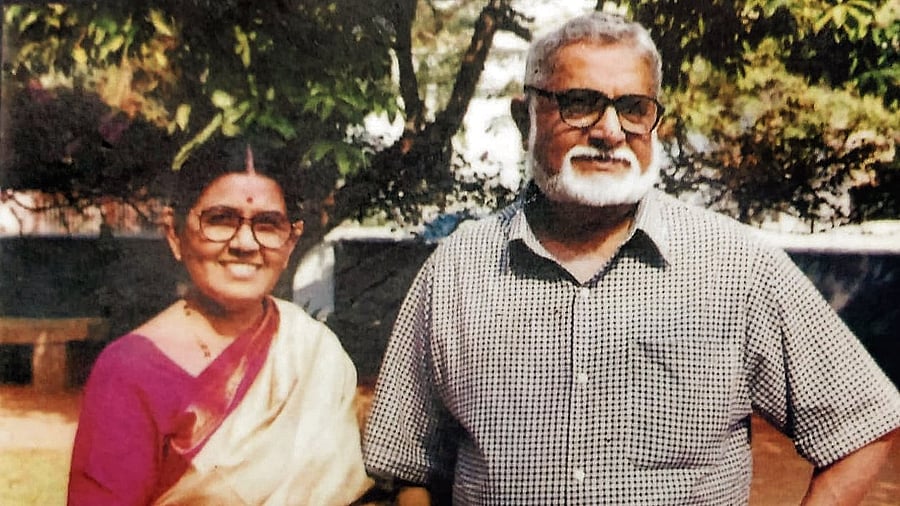

Credit: Rajeshwari Tejaswi

Kannada poet, dramatist, writer of fiction, naturalist and environmentalist Poornachandra Tejaswi expanded the canvas of Kannada writing probably more than any modern writer. Highly original and innovative, he constructed a synthetic vision of the natural and social worlds as inalienably bound together and of a cosmos whose mysteries are endless.

These mysteries are a challenge to the human intellect and also demand a full-blooded holistic response from the body and the mind. A passionate believer in science, in his fiction, Tejaswi carried his readers to the very edge of rationality, where the experience is nearly mystical.

In his novel ‘Carvalho’, the eponymous scientist and his ragtag team of explorers confront the flying lizard, a symbol of the missing link and transitions in evolution. Tejaswi, a master creator of unforgettable metaphors, portrays the scientist and his team as holding hands to make the ‘great chain of being’, itself a part of ecology, in which all things and beings are interdependent.

In this vision, the modern scientist Carvalho, the born naturalist Mandanna, the cook Biryani Kariyappa and the narrator (for whom the exploration is both an education and a mystical experience), transcend the hierarchies of class, caste and status in the presence of the flying lizard, hiding in itself mysteries of millions of years of evolution. It is an epiphany of a cosmos which runs on physical laws which reason can comprehend and science can explain. But in experiencing it, we are made to trespass into the tantalising mysteries of the ever-expanding universe.

A socialist, Tejaswi wrote short stories, novels and tales of ecology which constantly highlight the extraordinary wisdom and humanity of individuals like Masti, Byra Cheenkra Mestri, and a host of others, who were marginalised by society. Tejaswi said that the fate of marginalisation, exclusion and invisibilisation has already been finally written in the route to ‘progress’ chosen by the modern world.

This is a world which is anthropocentric and believes that nature was created for reckless consumption by human beings — a world alienated from the knowledge preserved by the subalternised communities. He suggested that this traditional knowledge could have been integrated with modern scientific knowledge.

Prominent themes

Credit: Rajeshwari Tejaswi

Tejaswi began his literary career under the influence of the Kannada Navya (modernist) movement. His early works deal with philosophical questions regarding the fragmentation of the self and the absurdity of experience. In 1973, he published ‘Abachurina Post Offisu’, a collection of stories he had written after turning away from the modernist mode. In the preface, titled ‘Toward a new horizon’, he declared that he had abandoned the solipsistic, individual-centred subjective exploration of that mode.

The stories in his collection were about the experiences of a rural, small-town society in the Malnad region where he started a new life as a farmer and coffee planter. He explained that his education and training had made it difficult for him to understand the complexities of this social world. The remarkable stories in the collection do not feature a romanticised portrayal of rural society.

Caste politics, irrational behaviour, the role of the criminal world in looting natural resources, communalised religions and a corrupt bureaucracy have created a society and world, which is both absurd and pathetic. Tejaswi writes in the colloquial speech of the denizens, replete with colourful curse words and picturesque images. Tabara, whose pension is never settled; Krishnappa’s elephant, blamed for all the mishaps; and Engta, the snake charmer, constitute a gallery of unforgettable characters.

Ahead of the times

Tejaswi plays the sitar

Credit: Rajeshwari Tejaswi

Tejaswi’s major novel, ‘Chidambara Rahasya’ (1985), is a prophetic work in its depiction of a small town ending up in a conflagration owing to criminalised communal politics, petty rivalries and the destruction of the ecology of a region which was once like ‘the Switzerland of Karnataka’. Moral decline and political corruption collaborate with environmental destruction and with ‘the aged culture’ of a society unable to sustain the community. Only Rafi and Jayanthi, in love, like Adam and Eve, witness the end of the old world’s self-destruction while taking shelter on the hilltop.

‘Jugari Cross’, an extraordinary suspense thriller, is about the adventures of a couple pursued by criminals and experiencing first-hand the dark mysteries of the criminal world. At the heart of the two novels is cardamom, now caught in a web of international trade conspiracies. ‘Jugari Cross' powerfully evokes the sinister nature of globalising trade, where the unseen ‘Boss’ masterminds a network of crime. However, the novels, despite a sombre view of the contemporary world, are narrated with amazing variations, humour and intricate plots. Tejaswi uses popular sub-genres of the novel such as the adventure tale, suspense thriller, crime fiction and low mimetic satire. This has made him the most popular writer for thousands of readers for whom he is a cultural icon. He is already a legend, with anecdotes about his lovable eccentricities shared by the younger generation.

Recently, the author’s collected works were compiled and released in 14 volumes, edited by K C Shiva Reddy.

Tejaswi was a world-class naturalist and a gifted photographer. He helped readers experience and see the extraordinary forms, shapes, colours and sounds of nature. He believed that since institutional religion declined and became bereft of transformative power, it is science and rationality, touched with a sense of mystery, that should take its place. The world of nature can endlessly rejuvenate itself. Would the human social world be able to remake itself after all the harm it has done? Tejaswi’s enchanting — at times enigmatic — smile hides the answer.