It was in July 2014 when incumbent Chief Minister H D Kumaraswamy, then an opposition leader, initiated a heated debate in which he took the Congress government to task over the state of waterbodies in Bengaluru. In October that year, the state Assembly formed an 11-member House Committee headed by former Speaker KB Koliwad. The panel was to look into encroachment of lakes in and around Bengaluru. Storm water drain encroachments also came under the committee’s purview.

Prior to the formation of the committee, a special drive to remove encroachments of tank beds in Bengaluru was abruptly halted. There was public outrage over demolition of houses near the Puttenahalli lake because it was the Bangalore Development Authority (BDA) that had permitted them to be built. The BDA later admitted, shockingly, that it had formed 23 layouts on tank beds.

The House committee came as a blessing in disguise for the state government and erring officials. It was decided to halt demolition of encroached properties on BDA layouts until the House committee came out with its report.

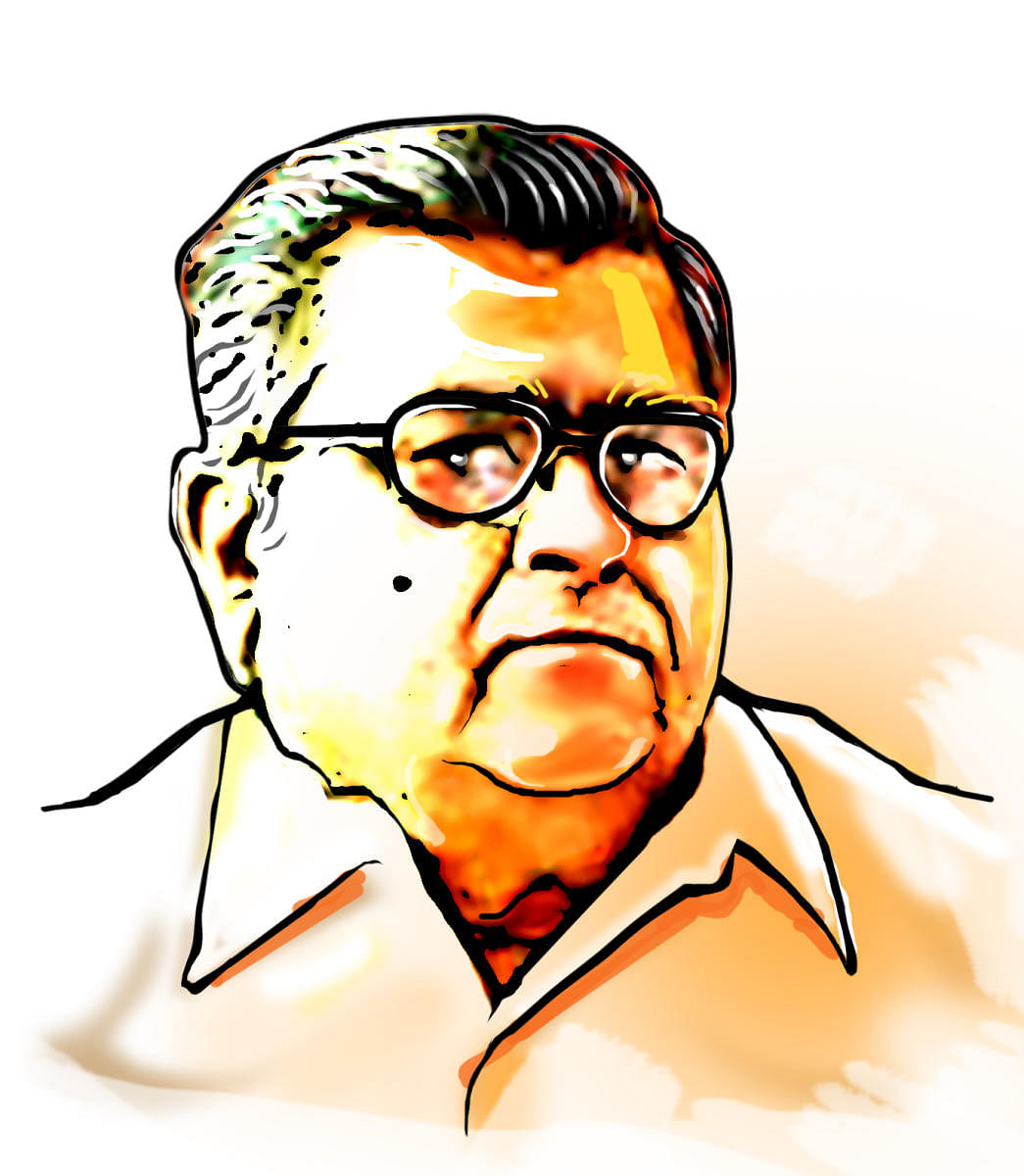

Thus began the saga of officials and builders taking shelter under the Koliwad committee, which took three full years to come out with its final report that experts say was not only vague but also fraught with contradictions.

The committee’s report stated that 501.11 acres of the network had been encroached by 2,083 encroachers. Authorities began passing the buck on clearing encroachments while the committee dragged its feet.

The Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP), which was dependent on surveyors to identify and mark drain encroachment, pointed fingers at the Revenue Department, which in turn looked towards the House committee for its final report. In November 2017, the committee tabled its final report before the Legislative Assembly. It suggested a way out: diversion of drains wherever possible. “The natural drains that carried rainwater along the slope to join another canal have been altered to benefit urban projects,” the committee noted. “It must be observed here that we must consider existing drains that are carrying out the function of the natural system that once existed. Otherwise, trying to restore the natural system would involve cancellation of projects and destruction of the location, which is not appropriate.”

In other words, the committee, while acknowledging that drains had been diverted, legitimised it.

In another recommendation, the committee asked the government to restore drains where the alternative canals had failed. “In such cases, the committee recommends indiscriminate removal of encroachments regardless of the person or building involved,” the report stated.

“It is deplorable that the committee brought legalities into the illegalities,” said water expert V Ramprasad. “The valley contours of Bengaluru will not support diversion of drains, because water will invariably flow in the natural slope,” he pointed out.

Around the same time the Koliwad committee submitted its report, the Environmental Management and Policy Research Institute (EMPRI) also finalised its draft report on Inventorisation of Water Bodies in Bengaluru Metropolitan Area. Contrary to the Koliwad committee, the EMPRI recommended eviction of drain encroachers.

“The storm water drains are like veins, which feed water to the waterbodies. The diversion of storm water channel has led to the dry condition of the waterbodies, so the diversion should be prohibited and should not be included in the waterbodies rejuvenation activity,” EMPRI stated.

Defending the committee’s report back then, Koliwad had said: “The government can explore the possibility of diverting Rajakaluves, if possible, instead of bringing huge structures down.”

This came as a relief to a hospital belonging to senior Congress leader Shamanur Shivashankarappa and the house of Sandalwood actor Darshan, both located in Rajarajeshwari Nagar. The hospital and the actor’s house were issued demolition notices, but alas.

In a landmark ruling in May 2016, the National Green Tribunal (NGT) had redefined buffer zone as 50m from the edge of primary Rajakaluves, 35m from secondary Rajakaluves and 25m from tertiary Rajakaluves. Construction activity was prohibited in this space. The Koliwad committee stated that since the NGT order was being heard by the Supreme Court, the government was asked to act based on the outcome of the case.

The Koliwad committee also refrained from naming erring officials, builders and government bodies that encroached waterbodies and drains. Instead, it recommended setting up of a judicial commission to identify and act against those responsible for encroachments.

The committee did suggest a way forward for the Urban Development Department. It asked authorities to ensure, during approval and formation of new layouts, the drainage systems are capable of carrying water in line with the watershed requirements while retaining the direction in which the water naturally flows in that region. The Koliwad committee report is pending before Chief Minister H D Kumaraswamy, whose pronounced concern for waterbodies led to the House panel’s birth.