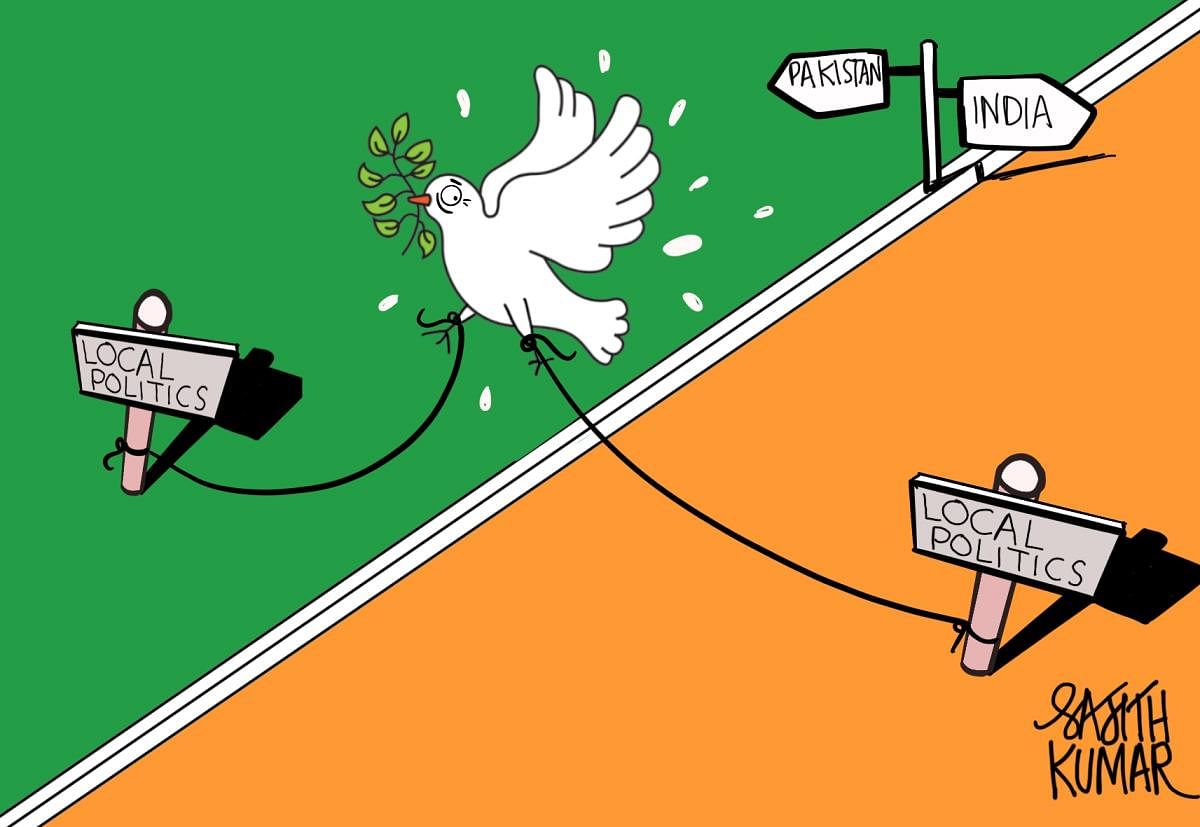

The single biggest takeaway from the unheralded ceasefire between India and Pakistan, announced by their Director Generals of Military Operations that went into effect at midnight on February 24-25, is what the Narendra Modi government is not saying.

The silence is deafening.

A week after the announcement, all that the Ministry of External Affairs spokesperson would say, as he deflected queries over the back channel talks which Pakistan has openly admitted to, is that India would like “normal ties with all its neighbours, including Pakistan.” The obfuscation raises more questions than answers. First, who was the real mover and shaker behind the backroom talks? Second, if it is the Pakistan Army, as many have now concluded, why would it initiate such a dialogue, and at whose behest? And why would India play along?

It’s not that there were no signals in the days leading to the strategic shift. But distracted by the shrill, repetitive rhetoric, post Uri and Pulwama, few saw Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan cleared to fly over Indian airspace en route to an official visit to Colombo (48 hours before the ceasefire became public) as anything more than a gesture of Indian goodwill. Pakistan army chief Gen. Qamar Javed Bajwa’s intriguing “it’s time to extend the hand of peace in all directions” in early February, did fly in the face of convention, but again, it didn’t seem to denote that a thaw was in the offing. If a thaw is what this is.

In fact, with the anodyne statement by Imran, that “the onus is on India”, that “India must take steps to meet the longstanding demand of the people of Kashmir to seek self-determination,” it seemed the very opposite, indeed business-as-usual. Islamabad not raising Kashmir during the virtual SAARC summit that Prime Minister Modi had addressed on February 17, dismissed as nothing but a one off.

Instead, there are now rising expectations of a complete cessation of hostilities on the International Boundary and the Line of Control, as well as the 4,500-km Line of Actual Control where India and China agreed to a simultaneous withdrawal of troops after a tense nine-month standoff. That it coincided with the anniversary of the cross-border strike on the Balakot terror facility inside Pakistan has only stoked further expectations of a breakthrough on Jammu and Kashmir.

That may be belied. Hotline contacts between DGsMO, that have been in place since the Karachi Agreement of 1949, and the 1971 war, are a means to de-escalate local tensions. Maj. Gen. Nauman Zakaria and Lt. Gen. Paranjit Sangha are not the first ones use the line. But it must be said that this return to the ceasefire agreement of 2003 between former Prime Minister Atal Behari Vajpayee and former Pakistan President Pervez Musharraf is not a military-to-military arrangement alone. The language of the agreement has a diplomat’s imprimatur. Speculation is but natural that High Commissioners to the respective capitals will be appointed; followed by a return to a semblance of a dialogue, at regional and international fora, the convening of a possible SAARC summit in Islamabad -- one of Pakistan’s longstanding demands -- the SCO and Heart of Asia Conference, alongside confidence-building measures such as the re-opening of cross-border trade and reuniting divided families.

The most telling part of the joint statement is that “the two countries agreed to address each other’s core issues and concerns which have the propensity to disturb peace and lead to violence.” One of the primary “concerns” -- cross-border shelling along the 450-mile-long LoC – will, of course, end forthwith. While Pakistan notched up over 5,000 violations in 2020, India’s adoption of an equally aggressive doctrine of pre-emptive strikes has kept both armies pinned down.

The second point of note is the more deleterious mention of “core issues”. Are we to assume that the Pakistani military establishment will resume talks even if India does not restore Article 370 and full statehood to Jammu and Kashmir? And that PM Modi will drop his “no talks till terror ends” hard line against Pakistan, begin face-to-face talks, and revisit the four-point formula that Musharraf offered to former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh? That formula would have seen a complete withdrawal of troops, free movement of Kashmiris across the LoC, self-governance without independence, and India and Pakistan continuing to administer the two-part state alongside Kashmiris.

We may be jumping the gun, but if Gen. Bajwa is the prime mover and shaker behind this peace initiative – he is reportedly the one who dialled National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, not Imran Khan – will he do a Musharraf and accept the current status quo in his bid to buy peace with India? Gen. Bajwa, whether inimical to India’s rise or not, must have noted US President Joe Biden steadily reclaiming the space ceded by his predecessor Trump to a rising China, and realised the need to distance himself from the US-China and China-India confrontations. The Pakistan Army, even at the height of the Ladakh conflict did not mobilise troops to its border with India.

While it’s not clear if Imran Khan is even on board, Moeed Yusuf, Special Adviser to the Pakistan Prime Minister, who disavowed any claim to being the backroom boy talking directly to Doval, had actually let the cat out of the bag when he let it slip to a prominent Indian journalist that informal conversations had been taking place.

The speculation that India and Pakistan were talking did surface when Trump made his repeated offers to mediate. More an indication that the US was aware of the low-level ongoing intelligence contacts, the talks that took on an added urgency four months ago, when the Pakistan army supremo saw which way the wind was blowing. Most of the interaction reportedly took place in London.

There was one other player that pushed the Pakistan military into effecting the sea change within its own strategic calculus and prodded its military chief into reaching out to India – the United Arab Emirates, fast emerging as India’s key partner in the Gulf, and whose remit has given it growing heft in the Gulf.

Pakistan’s ‘bad boy’ image in the neighbourhood, in no small measure due to the legion of terrorists of varying nomenclature, who prey on the unsuspecting at home, in Afghanistan and in Jammu & Kashmir, all operating from safe havens within Pakistan, has kept it on the ‘grey list’ of the Financial Action Task Force, thereby restricting loans from various development banks. With the perpetrators of the 26/11 Mumbai carnage remaining unpunished even after 12 years, and now Ahmed Omar Saeed Sheikh, mastermind behind the gruesome decapitation of American journalist Daniel Pearl, set free, Pakistan’s inability to end the FATF over-watch, may in some measure have been responsible for the reset. For it needs the help of not just China and Turkey, but also of the United States, the EU, as well as India.

Imran Khan’s inept handling of the economy, weighed down by China’s untenable CPEC project which the army has been forced to safeguard after repeated attacks by Baloch and Pashtun separatists, coupled with the ill-advised damaging of ties with Saudi and UAE, and now the popular people’s movement gathering pace against the cricketer-turned-politician, is forcing Gen. Bajwa to reset the internal narrative as well as the external. As he scouts for an acceptable alternative to Imran, the army’s recalibration of ties with India may have also been driven by the need to demonstrate to Biden that it can bury the hatchet with an arch rival and create an atmosphere for peace, and can be trusted to do the same in Afghanistan, where the present US leadership, although wary of Pakistan’s propensity to retake power in Afghanistan through the Taliban back door, has openly consulted with Gen. Bajwa on the Afghan endgame.

As PM Modi seeks to reinvent himself in this all-new avatar, going from strident nationalist to venerable sage, the move to quiet the border does rob him of the all too convenient trope of Pakistan as the permanent enemy, which has won him a cult following at home and abroad. Why would he give that up when a slew of critical state polls loom?

Is it because Delhi feels a need to mend ties with Pakistan as a first step towards ensuring that the Asia Cup, a mega money-spinner, is indeed played at home? If that were to happen, we may even see a Modi-Bajwa love fest, a la Howdy Modi, at the newly named Narendra Modi Stadium at Motera! Peace in Kashmir? That can wait.

(The writer was formerly Foreign Editor for the Dubai-based Gulf News and has reported extensively on Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka and the Middle East)