By Sudhi Ranjan Sen and Bibhudatta Pradhan

As Prime Minister Narendra Modi meets Russia’s Vladimir Putin and attends a summit with China’s Xi Jinping on Friday, he’ll need to avoid looking too chummy with the US’s two top adversaries.

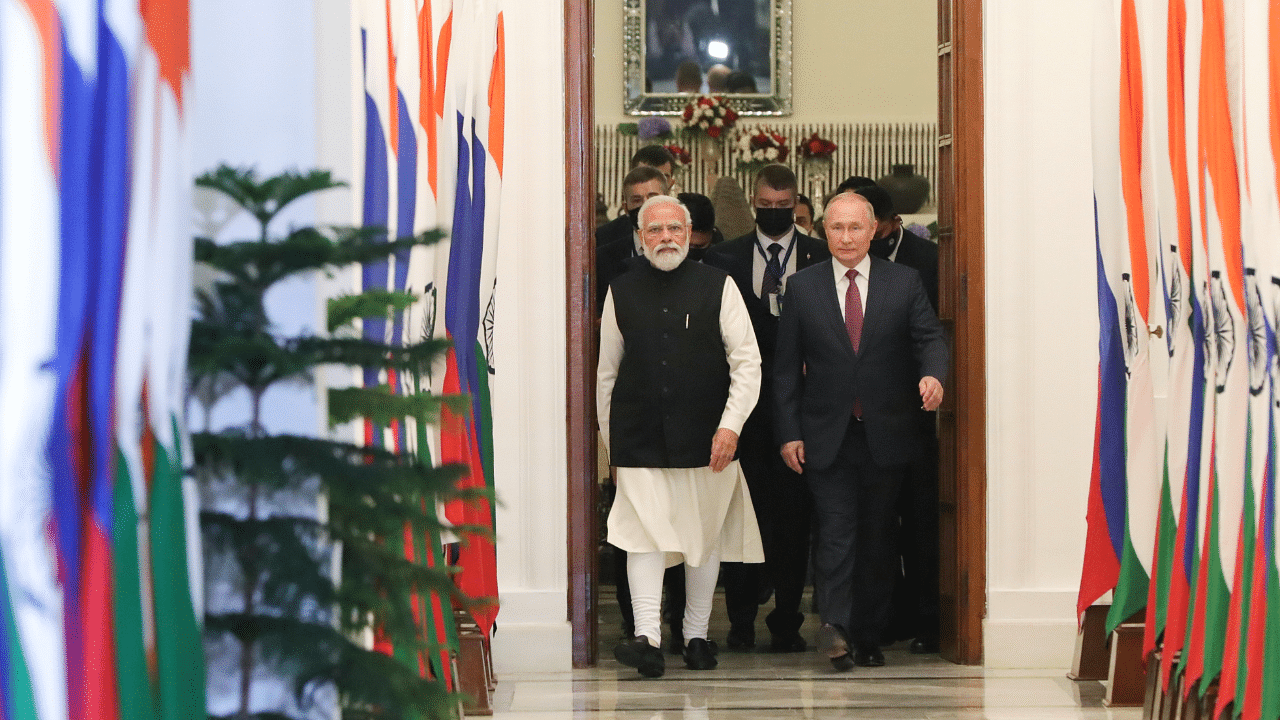

Modi’s face-to-face meeting with Putin will take place Friday in Uzbekistan, where a host of leaders are gathering for a summit of the Chinese-founded Shanghai Cooperation Organization, a group intended to counter the US-led global system. At that event, he’ll also rub shoulders with Xi, whom Modi hasn’t met in person since late 2019.

With Russia’s war in Ukraine in its seventh month, India has emerged as one of the biggest swing nations. The US and its allies have so far largely avoided pressuring New Delhi over its close ties with Russia, a key supplier of weapons and energy. That’s partly to keep Modi on its side against China in part through the Quad, a grouping that also includes Japan and Australia.

Modi so far has managed to thread the needle between the two sides while advancing India’s own interests. He’s sought cheaper oil and much-needed weapons, to counter Beijing’s aggression along their disputed Himalayan border and more investments from the US and its allies seeking to diversify supply chains away from China.

But whether he can keep that up is another question. The early tolerance for India’s position, along with its insistence that it would take time to unwind its deep security relationship with Russia, is beginning to run into greater resistance as the US and its allies ramp up efforts to impose a cap on the price for Russian oil to cut Putin’s income.

“India’s neutral public positioning on the invasion has raised difficult questions in Washington DC about our alignment of values and interests,” said Richard Rossow, a senior adviser on India policy at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “Such engagements -- especially if they trigger new or expanded areas of cooperation that benefit Russia -- will further erode interest among Washington policy makers for providing India a ‘pass’ on tough sanctions decision.”

So far, the Biden administration has signaled it’s not interested in sanctioning New Delhi over its recent decision to buy the S-400 missile defense system from Russia. Turkey’s purchase of the same system deeply damaged US ties with the NATO ally.

Yet friction points are emerging. India has been pushing back on a price cap on Russian oil suggested by the US as its crude imports surged five times to cross $5 billion in the three months to the end of May.

Last week, the White House approved a $450 million package to upgrade the F-16 fighter jet fleet of India’s historic rival Pakistan -- a move New Delhi opposed.

And India also angered Japan by recently joining the Russia-led Vostok-2022 military exercises held around a group of islands known as the southern Kurils in Russia and the Northern Territories in Japan -- a territorial dispute that dates back to the end of World War II. India ended up scaling back its participation in the war games -- especially staying out of naval drills -- out of deference to Japan, but it left a mark.

One Japanese official, who asked not to be named discussing a sensitive topic, asked whether India would be comfortable if Japanese troops had participated in drills with Pakistan’s military but merely skipped exercises in the disputed region of Kashmir.

India’s Foreign Ministry didn’t respond to a request for comment. Japan’s Foreign Ministry didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment made outside of office hours.

“The challenge for India is managing a declining relationship with Russia, nurturing a growing relationship with the US and securing its interests on all sides as a growing power,” said Indrani Bagchi, chief executive officer of the Ananta Aspen Centre, a research group on international relations and public policy. “No matter how much India wants to maintain the Russia relationship, this is going to get more difficult as time goes by.”

A State Department spokesperson said the US has reiterated its hopes that India will not choose to align itself with Moscow, or the consequences of Russia’s war against Ukraine.

“We have expressed concern at the highest levels about actions which could undermine international efforts to pressure Russia to end its war on Ukraine,” the spokesperson said.

Modi appears aware of the optics toward the US. He flew into Uzbekistan late on Thursday, missing an official dinner to kick off the Shanghai Cooperation Organization summit that would’ve produced plenty of photo opportunities with both Xi and Putin, according to people familiar with the situation, who asked not to be named.

“At the SCO Summit, I look forward to exchanging views on topical, regional and international issues,” Modi said in a brief statement before heading to Uzbekistan.

India’s partners in the West will be closely watching the tone of any statements after Modi’s meeting with Putin. One particular area of interest is trade: In the first seven months this year, India’s imports from Russia stood at a little over $13 billion compared with just $2 billion a year earlier, according to Commerce Ministry figures. India’s exports to Russia dipped to $700 million in the same period compared to $950 million a year earlier.

While India’s historical connection with Russia will be tough to break, officials in New Delhi are more wary of China. The “no limits” friendship reached by Xi and Putin earlier this year also may factor into India’s long term strategic planning as tensions with China continue to simmer along their contested Himalayan border despite a recent pull-back of troops.

“Increasingly there are suggestions that Russia will largely follow China, especially after the Ukraine crisis,” said Harsh Pant, a professor of international relations at King’s College London. “And that is going to be one big part of the puzzle that India will have to solve.”