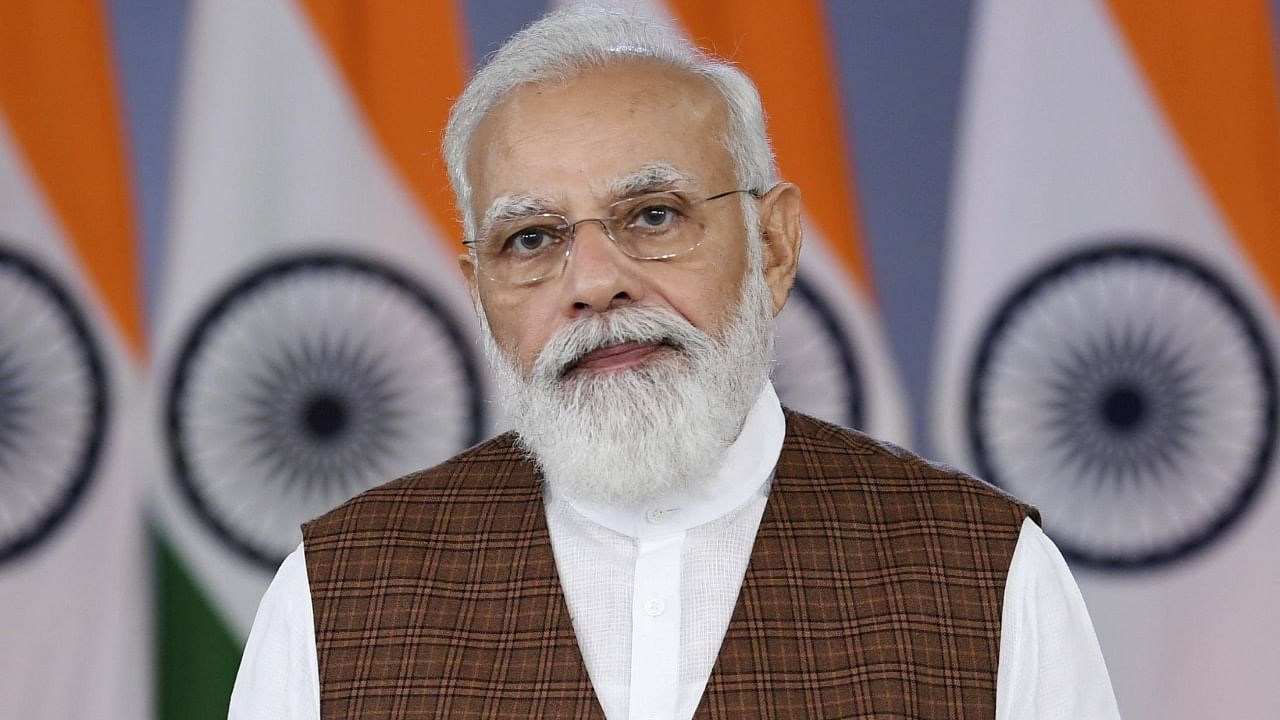

Three weeks after he commenced his first term in the Prime Minister’s Office in New Delhi with a glittering swearing-in ceremony attended by the leaders of several South Asian nations, Narendra Modi chose Thimphu as his first port of call. The visit to Bhutan on June 15 and 16, 2014 had all the trappings that over the next few years would turn into signature optics of his foreign travels. He got off his car, waved at the cheering roadside crowd, shook hands with people and addressed a joint session of Parliament of Bhutan, in addition to meeting King Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk and the then Prime Minister Tshering Tobgay.

His second foreign destination in the neighbourhood was Kathmandu, where he visited on August 3 and 4, 2014 and met then Nepalese Prime Minister Sushil Koirala. He also visited Myanmar within six months after taking over as the Prime Minister of India. And, by the end of 2015, he not only toured Bangladesh and Afghanistan, but also made a surprise visit to Pakistan, to convey birthday greetings to his counterpart M Nawaz Sharif, who in May 2014 attended his swearing-in ceremony in New Delhi.

The central message the PM sent out during his visits to South Asian nations was that India led by him would pursue a “Neighbourhood First” policy. He often invoked his “Sabka Sath Sabka Vikas” mantra during visits to the countries in the region, underlining that his government wanted to make the neighbouring nations part of the growth and prosperity of India.

Modi continued to pursue his “Neighbourhood First” policy in his second term in the office of the Prime Minister. He chose Maldives and Sri Lanka as his first foreign destinations just a few days after taking oath for the second time on May 30, 2019, although he had visited both the countries during his first term too. He had his second visit to Bhutan in August 2019. Though the Covid-19 outbreak kept him grounded for more than a year, he restarted his foreign tours with a visit to Bangladesh on March 26 and 27 this year.

But how has his much-hyped “Neighbourhood First” policy fared so far?

The escalating tension along India-China disputed boundary brought to the fore the strategic rivalry between the two nations. With the soldiers of the Indian Army and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) engaged in an eyeball-to-eyeball stand-off along the Line of Actual Control (LAC) in eastern Ladakh for the past 18 months, what has come under scrutiny is the Modi Government’s “Neighbourhood First” policy and its successes and failures in countering China’s renewed bid to woo the South Asian nations into its orbit of influence and build strategic assets around India.

The stalemate in negotiations between the military commanders of India and China to resolve the stand-off, the PLA’s continuing build-up and its recent incursion bids into Uttarakhand and Arunachal Pradesh and the Indian Army’s countermeasures of late fuelled speculation about tension spreading from the western sector to the middle and eastern sectors of the disputed boundary of the two nations.

China’s “iron-brother” Pakistan is now set to gain a strategic edge against India as its proxy Taliban is now back to power in Afghanistan. The Prime Minister, himself, of late warned about the advanced weaponry the United States and its NATO allies had left behind in Afghanistan and the possibility of such military hardware posing a threat to the stability in the entire region. The backchannel talks between India and Pakistan, facilitated by United Arab Emirates, did result in a deal to strictly adhere to the 2003 ceasefire agreement along the Line of Control (LoC) and the undisputed stretch of the border. But the Indian Army chief Gen M M Naravane recently said that the Pakistan Army had again started flouting ceasefire and infiltration of terrorists from Pakistan into Jammu and Kashmir of India also resumed.

Thimphu stood by New Delhi all through the 74-day-long stand-off between the Indian Army and the Chinese PLA in Doklam Plateau in western Bhutan from June 16 to August 28, 2017. China, however, continued to step up pressure on Bhutan, with the PLA gobbling up large swathes of land of the tiny nation, setting up villages, military bases and communication posts. The territorial row between the two nations was limited to China’s claim on 764 sq km of areas – 269 sq km in west and 495 sq km in north-central Bhutan. But China last year upped the ante and also claimed the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary in eastern Bhutan as part of its own territory. The sanctuary is close to Arunachal Pradesh where China has been claiming around 90,000 sq km of territory of India. Bhutan rejected the new claim made by China, but the two nations on October 14 announced signing of a three-step roadmap to resolve the boundary dispute. New Delhi has reasons to be concerned. Beijing had earlier asked Thimphu to accept China’s sovereignty on areas around Doklam in western Bhutan in exchange for it giving up claim on areas in north-central Bhutan. If China gains control of Doklam Plateau, it will make it easier for its PLA to conduct military manoeuvres aimed at blocking the Siliguri Corridor – the narrow stretch of land linking India’s North-East with rest of the country.

Strong sentiments

Nepal is one of the South Asian nations where China has been trying to elbow out India. The Modi Government’s response to the new constitution of Nepal in 2015 triggered strong sentiments against India. New Delhi was accused of imposing an unofficial economic blockade, choking supply of essentials from India to Nepal. Just weeks after the stand-off between the Indian Army and the Chinese PLA started in April-May 2020, Prime Minister K P Sharma Oli’s Government in Kathmandu lodged protest over a new 80-kilometer-long road New Delhi built from Dharchula in Uttarakhand to the Lipulekh Pass – an India-Nepal-China tri-junction boundary point. It alleged that the road passed through Nepal – a claim dismissed by India. Kathmandu, however, went ahead, published a new map, which showed nearly 400 sq km of India’s areas in Kalapani, Lipulekh Pass and Limpiyadhura as part of Nepal. It also got the Nepalese Parliament amend the country’s constitution to endorse the new map. Though a new government led by Sher Bahadur Deuba of the Nepali Congress has now taken over, it will remain politically difficult for any successive dispensation in climbing down from the maximalist position Nepal already took in its territorial dispute with India.

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina’s Awami League government in Dhaka has been friendly to India. But China has of late stepped up its attempt to spread its tentacles in Bangladesh, with soft loans for infrastructure projects and tariff concessions. Hasina has also been upset over the Modi Government’s Citizenship Amendment Act and the process to update the National Register of Citizens in Assam as well as some comments by the top BJP leaders about alleged illegal migration from Bangladesh to India. New Delhi has also been concerned about rising radicalism in Bangladesh.

President Ibrahim Mohamed Solih’s government in Maldives replaced his predecessor Abdulla Yameen’s pro-China policy with an “India First” policy. But an “India Out” campaign gained momentum in the Indian Ocean archipelago, apparently launched and run by the elements supported by Pakistan and China. India responded cautiously to the coup d’état in Myanmar to avoid disturbing its relations with the South East Asian nation’s military leaders, who always had close relations with the Chinese PLA. India’s cautious and muted response to military takeover drew flak from the pro-democracy activists in Myanmar.

China’s debt-trap diplomacy earlier made Sri Lanka leasing out its Hambantota Port for 99 years, causing security concerns for India. The government led by President Gotabaya Rajapaksa and Prime Minister Mahinda Rajapaksa scrapped a trilateral agreement Sri Lanka had earlier signed with the governments of India and Japan for development of the East Container Terminal of the Colombo Port. It, however, clinched a deal with the Adani Group of India for development of the West Container Terminal of the port. But New Delhi remains concerned over the Colombo Port City Economic Commission Bill, which could end up allowing China to virtually establish a colony in Sri Lanka – not far from the southern tip of India. China is also trying to build infrastructure projects in Tamil-majority northern province of Sri Lanka, causing much unease for India.