The stock market has been booming during 2020. The Nifty touched 14,000 and went up be nearly 15% during the year. The pharma component went up by 60% during the year. The coronavirus pandemic and then the lockdown came together to give the Indian stock market a huge fillip as it went from strength to strength, day after day. On the Ease of Doing Business, India leapt forward and ended at the 63rd position, a huge improvement from the 142nd rank in 2014. This kind of improvement is simply unprecedented. On a completely different playing field, India scored a historic win against Australia at the MCG to end the year on an absolute high.

However, what cricket fans will remember for a long time is the 36 all out at Adelaide, India’s lowest test score ever. In quite the same manner, what 2020 will be remembered for is not the scorching pace set by the share brokers or the remarkable ease of doing business (if it indeed is) in India. This disastrous year will remain in memory for having stopped, and dragged back, India in its tracks on all development fronts.

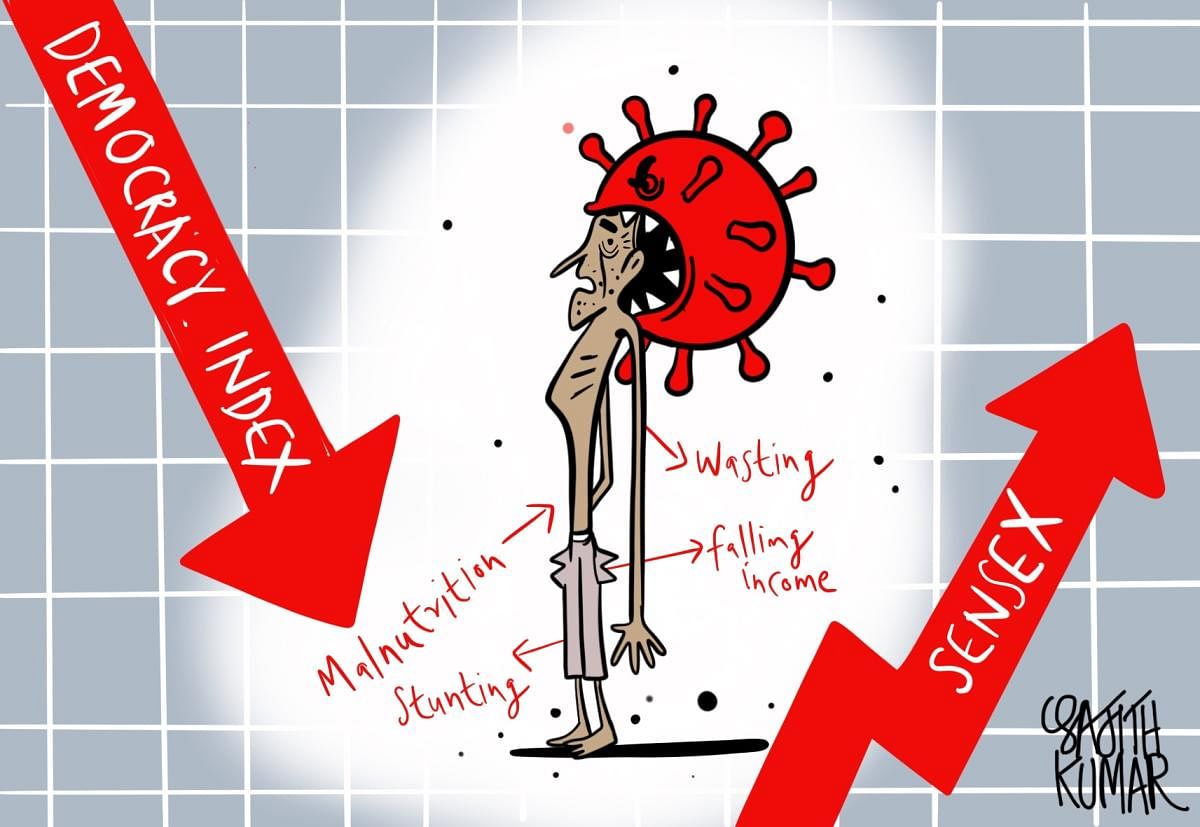

But even before the pandemic, over the last few years, India has been slipping on ensuring food to the poorest of the poor, and malnutrition has worsened. Joblessness had skyrocketed to unprecedented heights even before the 2019 elections. And in 2020, thanks to the pandemic, millions also lost their access to education. The UNDP’s Human Development Index for 2019 saw India’s ranking fall to 131. The HDI is a robust evaluation of health and education access and availability in 188 countries. India’s fall, over the last few years, is in many ways unprecedented -- and a clear indictment of poor public policy.

The Global Hunger Index put us to shame. We are now in the “serious” hunger category, ranked 94 among 107 countries. To add insult to injury, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Nepal have done better than us. The reasons behind this debacle is not difficult to identify. Demonetisation and then GST caused large-scale unemployment and a real fall in consumption expenditure among the extremely poor and the marginalised. The pandemic lockdown this year made things worse by denying migrant labour and the vulnerable any access to food. Overnight on March 24, mid-day meals were withdrawn in many states and Anganwadis closed, leaving poor children without the single hot meal they would have every day. No wonder 14% of India is now undernourished and 37% of our children stunted, and we are yet to see the 2020 figures.

Over the last 15 years, India had made major gains on hunger and malnutrition. However, all those gains have receded now, especially in the last one year when the pandemic and the lockdown created misery and left millions without access to food and nutrition.

The National Family Health Survey-4 had shown that 38% of children under five are stunted, 21% are wasted, 36% are underweight, and 2% are overweight. However, it had also shown remarkable improvement in these indicators over the decade since 2005. However, NFHS-5, released this year, shows that we have lost all the gains made previously. Stunting has gone up in 13 states and the number of underweight children in 16 of the 22 states surveyed. And we haven’t even heard from some of India’s worst-performing states on these indicators.

On the education front, it’s the same story, although it will take time to obtain data and understand how many children have dropped out of the system in 2020. Schools were closed without any notice and for the last nine months, there has neither been any certainty of re-opening or over the way forward. The UN has estimate that 24 million youth will drop out of schools in the aftermath of Covid-19, with a large number of them in India. The much-touted shift to online education has made matters worse, widening inequality and the digital divide. Only 24% of our students have access to internet connections at home, according to the UNICEF.

In terms of overall access to the internet, the Freedom House Index noted that Internet freedom in India has visibly dropped in the last three years. We had the most number of internet shutdowns for any country in the world, and this does not even include the internet ban in Jammu and Kashmir. India’s position on the Freedom on the Net 2020 index fell from 55 to 51 out of 100 countries. India is ranked 47th on the Inclusive Internet Index of the Economist. Three years ago, India was at the 36th position. The digital divide has only been increasing, and this is bad news for those of us who believe that education and healthcare access can be improved using the internet and mobile telephony.

India’s ranking on almost all fronts, with the exception of booming stock market indices, has been on a decline for the last three years. In 2020, the downhill trend only accelerated. On all gender indices, for example, India stands among the laggards. The UN HDR noted that India’s female labour force participation was at 20.5% and that only 13.5% women hold seats in Parliament. On the World Economic Forum’s Gender Gap index, India has dropped four places since 2018, to settle at the 112th rank. It is estimated that it will take us another 100 years to close gender inequality on the political, health, nutrition and education fronts.

It is not surprising that India’s rank in the democracy indices also has been plunging. The EIU’s Democracy Index put India at 51, a fall of 10 ranks, citing the erosion of civil liberties in the country. The frequent bans on internet usage, large-scale suppression of protest and dissent, and the emaciation of the democratic process of law-making have ensured that India has steadily been falling on a variety of global indices. All this makes India’s ability to reach the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030 that much more in doubt.

Over the last 15 years, various tags have been applied to the country. India was to be a test case for democracy and a market-based economy that would produce and make each citizen happy and satisfied. What has happened is a never-before unemployment rate, such that our labour ministry has even stopped putting out unemployment figures anymore. Estimates suggest an increase of 140 million in the ranks of the unemployed since the lockdown. The MPCE has actually been coming down, which means that people are eating less and are buying lesser amounts of goods. Till this consumption goes up, any hope of an economic recovery will only be a dream.

India was supposed to become the world’s growth engine this decade, taking over from China. However, we have failed to take that leadership position. With domestic consumption slowing and a ‘middle-income trap’ beginning to be seen, India will not be able to wield enough clout to take a global leadership position. The US was the world’s growth engine in the post-World War 2 period; since the eighties, China progressively took up that mantle. It was just as China was slowing down in the 2010s that India was rising and was expected to take on the mantle. It is not surprising to hear that it is because India could not keep up its growth that the world economy has gone into a recession. India, instead of growing, has been declining over the last several quarters.

Finally, what is even more disturbing is when the global democracy index shows a value lower than what it was in 2006. Once again, the blame lies on one country that was expected to help increase the world’s democracy quotient. Instead, India has participated fiercely in first reducing its own democracy score, and has therefore contributed to the falling score of the world as a whole. It is indeed a matter of concern that a country that claims to be ranked right on top in garnering FDI, economic growth and a solid democratic foundation seems unable to prevent the slide downwards.

Just as the 36 all out score recently showed, it will now be exceedingly difficult to get back to the top, unless the government takes a clear set of corrective policy measures. It begins with acting as a responsible state in rolling out the Covid-19 vaccine quickly and free of cost and then, over the next several quarters, getting economic growth back on track. But it does not stop there. Health and education of the population will have to be top priority, but all of it can only be achieved by a return to democratic processes and decision-making and inclusivity.

(Amir Ullah Khan teaches economic policy at the Indian School of Business and the Nalsar University of Law)