Sunil Arora retired on April 13 with the dubious distinction of being the most controversial Chief Election Commissioner in recent memory. His was a surprise selection for the post as his name had figured in the PR woman Nira Radia tapes. Accused of helping the BJP with several decisions, he led the Election Commission in key decisions in holding the elections to five Assemblies including West Bengal’s, the most crucial one. It was an election that the BJP was aggressively obsessive in capturing West Bengal.

Though multi-phase polls have been the norm in Bengal, eight long phases are quite unprecedented. Observers note how constituencies have been grouped for each phase primarily to facilitate very busy leaders to fly in and address crowds and quite conveniently fly back to Delhi. Never before has Kolkata airport handled 140 chartered planes and helicopters in just five weeks and 90% of these were said to have been hired by the richest party, the BJP. While the Commission had always opposed secret donations to parties through ‘electoral bonds’, the Arora-led Commission did a U-turn before the Supreme Court last month. As a result, the opaque system that enriches mostly the ruling party, continues.

For many observers, it was surprising to see that right from the word go, the Commission’s decisions were more pro-BJP and anti-Trinamool Congress (TMC) led by West Bengal Chief Minister Mamata Banerjee, the most serious state-level challenger that Narendra Modi has faced since 2014. On January 28, a ‘Citizens’ Commission on Elections’ chaired by retired Justice M B Lokur presented its detailed report on how Electoral Voting Machines (EVMs) are susceptible to interference. Based on this, the TMC wrote to the Election Commission to take heed and ensure that votes cast are counted not only on EVMs but also to tally them with the VVPAT paper slips. VVPAT or Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail enables a voter who has pressed the EVM button to see a small slip pop up displaying the name of the chosen candidate, to reassure him or her.

After seven seconds, the printed slip moves automatically into a sealed box, but strangely enough, this paper trail is not counted by the Commission, except for a very small token number.

As Mamata felt unsure of the accuracy or vulnerability of both EVMs and VVPAT, she wanted that both be counted, which the Commission refused quite vehemently. It also refused to acknowledge the Justice Lokur Committee’s rather convincing report. Her other demand to reset the timers of VVPAT machines to 15 seconds to enable voters to comfortably verify their votes was also rejected, even though sufficient time is available. The Commission took refuge behind the Supreme Court’s last order dated April 8, 2019 that then Chief Justice Ranjan Gogoi had pronounced. In any case, this order rested on a palpably-exaggerated statement made by the Election Commission before it that total verification of paper trail slips may delay election results by five to six days. Experts are convinced that the counting of paper slips (bearing only one name) may not take more than six to eight hours at the most. A public demonstration would have solved the issue for ever, but neither the Commission nor the Court ordered for it. The BJP was, apparently, happy over the outcome.

Justice Gogoi’s order decreed that just five VVPAT out of the average of 180 to 280 assigned to polling stations per Assembly Constituency be counted. Though it was meant primarily for the 2019 polls, the Commission interpreted it as unchangeable forever and said so to whichever political party approached it. This stubbornness obviously lends credence to the apprehension that there may be serious mismatches if both EVMs and VVPATs are counted.

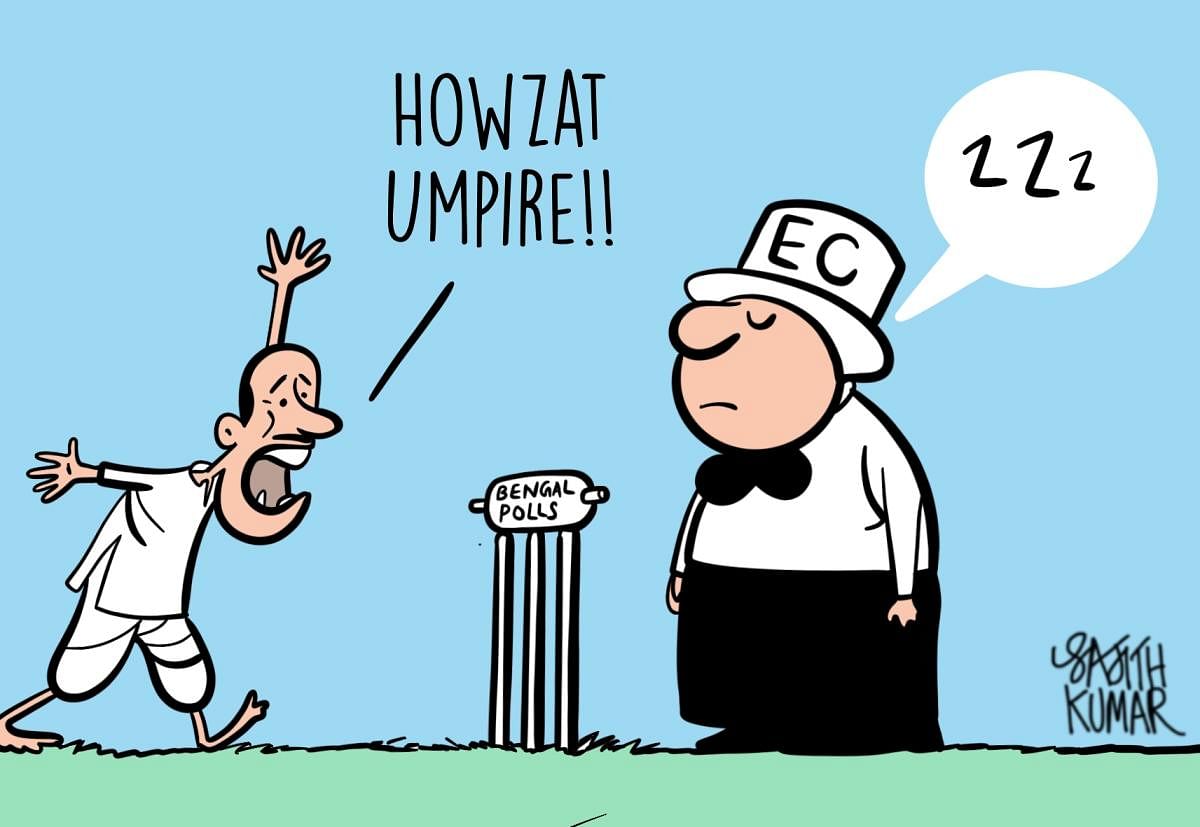

Apart from these policy issues that affect campaigning and results in West Bengal and elsewhere, constant irritants cropped up between a Commission criticised as biased and political parties in West Bengal. There have been repeated examples of violation of the Model Code of Conduct and the worst example of both sexism and offensive behaviour was made by Prime Minister Narendra Modi by calling out Mamata, “Didi-Ooo-didi”. There was an uproar among women’s groups and civil society against this but the Commission chose to remain silent.

Mamata Banerjee and Union Home Minister Amit Shah match each other in aggressive retorts but while several incendiary statements made by the latter, hinting at one community, were let off by the Commission, Banerjee was punished for hers. Much more intemperate than both is BJP state president Dilip Ghosh, who abusively threatens to break the bones of his opponents. He managed to get away scot free thanks to an indulgent Commission, but as soon as Arora retired, the restructured Commission handed out a warning and a penalty on Ghosh.

The most glaring instance of the Commission overreach was, however, seen when a Central Industrial Security Force section that had no experience of handling law and order, killed four voters by firing directly into their chests. This happened on April 14 during polls, at a remote polling station in Sitalkuchi in Cooch Behar district of north Bengal.

Under-policed

Though Central forces have often been utilised in under-policed West Bengal during elections, what is distressing is the provocative and rather-colonial manner in which they behave with local people. True, there are allegations of partiality against the state police, as were there during the Left regime, but in the past, no planned operation was ever launched by the Centre to run a parallel law and order machinery.

This is not permitted under the Constitution. This cavalier attitude became quite pronounced when, in violation of all existing orders and procedures, Central forces did not tie up with local police to patrol — even though they have no knowledge of the people or the topography.

The Commission appointed Vivek Dubey, handpicked from another state cadre, as ‘Special Police Observer’. Mamata has surely been quite vocal about this `highhandedness’ and had warned voters about interference. The Commission and he have not produced a shred of evidence (or visual) on why four impoverished local Muslim voters would attack central forces and what hurt they had inflicted on them.

When criticised, the Commission banned the entry of political leaders to the area. BJP’s state president justified the firing and killings and said more should happen if required. Rahul Sinha, another senior BJP leader, said, “Not four, eight people should have been shot dead in Sitalkuchi. The Central forces should explain why they killed only four and not eight”. The Commission’s bias is evident when it hardly took cognisance of the statement of Mamata Banerjee’s former minister- turned-opponent at Nandigram that ‘Mini Pakistans’ were being created.

What the BJP and the Commission do not realise is that with such overt partiality and domineering attitude, they are only helping Mamata Banerjee negate the anti-incumbency feeling that was quite visible in West Bengal.

(The writer, a retired IAS officer, is former CEO, Prasar Bharti; he is also former Chief Electoral Officer, West Bengal)