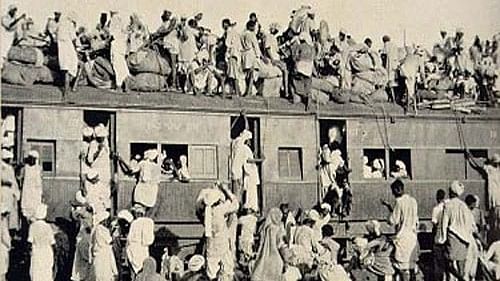

Overcrowded train transferring refugees during the partition of India, 1947. This was considered to be the largest migration in human history.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons

He was six years old when his family moved from Peshawar to India after Partition in 1947. They travelled for almost three days in a train with dead bodies, witnessing bloodshed and massacre across the new border that was created between India and the new-formed Pakistan.

Now in 2023, Peshawari Lal Bhatia, who retired from the Indian army as a colonel and lives in Noida, recalls the horrors of the Partition and how he became a refugee seven decades ago in his own country.

Bhatia was felicitated during the 'Vibhajan Vibhishika Smriti Diwas' by Uttar Pradesh PWD minister Brijesh Singh and Noida MLA Pankaj Singh on the eve of the 77th Independence Day here.

"I was five or six years old when I was put in a school there (Peshawar) with Urdu as the medium of teaching. I could not learn full Urdu because of what happened later. I can only read Urdu, not write it," he says, adding he still remembers many things but some memories have faded.

He said when they started from Peshawar, he was with his mother, siblings and some other relatives and carried whatever little luggage they could at the time.

"The trains in those days had a box-type design with benches all around it in the inside. We sat on the floor of the train. It took us between two-and-a-half to three days to reach from Peshawar to Amritsar," he said.

The trains in those days were very slow and Bhatia said he does not remember what the family ate or drank during the long journey, but he recalls being offered food at a station.

"There were two stations – Miyawali, which is a defence base of Pakistan, and Sialkot, where we were provided with hot food. Some local people had also turned up at the railway stations to see us, which included some Sardars who got us langar to feed," Bhatia said.

He has not forgotten how the train was sprayed with bullets when they were on board the train.

"At times people would get hit by those bullets. Some of the bodies were thrown out of the train. I don't know how I lost all fear. Then dead bodies did not frighten me,” he said.

When the train reached Amritsar the passengers were allowed to stay for around eight hours at the station where the Jana Sangha had set up relief camps. he said.

"I remember we were given meals and also some biscuits which are long and have sugar coated on it. We still get those biscuits. We were also given some clothes by them. After the short halt in Amritsar, the train resumed journey and dropped us at Nabha, near Patiala, where all passengers alighted," the Army veteran recalled.

He said during Partition, all displaced people who came to this side of the border settled wherever the train would stop as its final destination. Some settled in Punjab, some trains went to Bombay (now Mumbai), some to Calcutta (now Kolkata) and some to Bareilly in Uttar Pradesh. Many also reached and settled in South India.

"My father was into the trade of rock salt. At the time of Partition, he was in Kabul (Afghanistan) for work and not with the family. We lost him during the displacement. My mother, three-four uncles, their families and my three siblings were with me in Nabha," Bhatia said, adding in his speech later that his father was somehow reunited with the family one-and-a-half-year later in India.

He said around two dozen families who had come from Peshawar were put up in a 'haveli' in Nabha by the generous local landlord who had opened his doors for the displaced people.

"Life was tough. There was no financial income. At that time people of the Jana Sangha and the Akali Sikhs of local Gurudwaras helped up a lot. Someone gave a sewing machine to my mother, who used it and worked hard to make 4 or 5 annas a day -- which was all for our family to survive on," the octogenarian recalls.

Bhatia said Nabha is some 16 miles from Patiala and at a similar distance from Malerkotla, which was the only Muslim-dominated area in the region at the time. All Muslims who were displaced from Punjab, UP, or any other part, tried to reach Malerkotla and take shelter there.

He recalled watching communal killings, bodies being dumped in farmlands and how this common sighting eventually removed fear from his mind.

"In the mornings, we all kids left our homes in the haveli with a sickle and went to farmlands nearby. Many Muslims, who had fled the area to Pakistan, had left behind lot of vegetables in the farms. We would go there and pluck whatever vegetables we got and bring back to homes," Bhatia said.

"There were also bodies abandoned in the farms. Many of these dead people had bandages on their bodies. Bandages were wrapped on their arms, stomachs, heads, legs. Using the sickles we had, we would open those bandages to find that these bandages were bogus and beneath them the people had hid money, notes of silver," he said.

These people who were fleeing from this side carried money hiding them under bandages. Sometimes he and other kids would be lucky enough to find one, two or three notes.

"Once I found 26 rupees of silver – it was a huge sum. I immediately rushed home, running back five to six kilometers from the spot. My mother scolded me for coming back alone without my brothers," he said.

"It was a matter of survival for us. We found money from corpses. Somehow we managed to gather our bearings and move on with our lives. The locals would look at us and ask 'Ye refugee kahan ke aa gaye hain' (Where have these refugees come from?). Some of them would call us 'Fruji' instead of refugee in their local dialect, asking 's***e fruji kahan se aa gaye'. Anyway, we tolerated it as we in fact had become refugees but life moved on," Bhatia recalled.

He recalled the hardships his family went through but he managed to study in a school, went on to pursue engineering and right after the 1962 war with Pakistan he joined the Indian Army from where he retired as a colonel in the 1990s and settled in Uttar Pradesh's Noida, near Delhi.