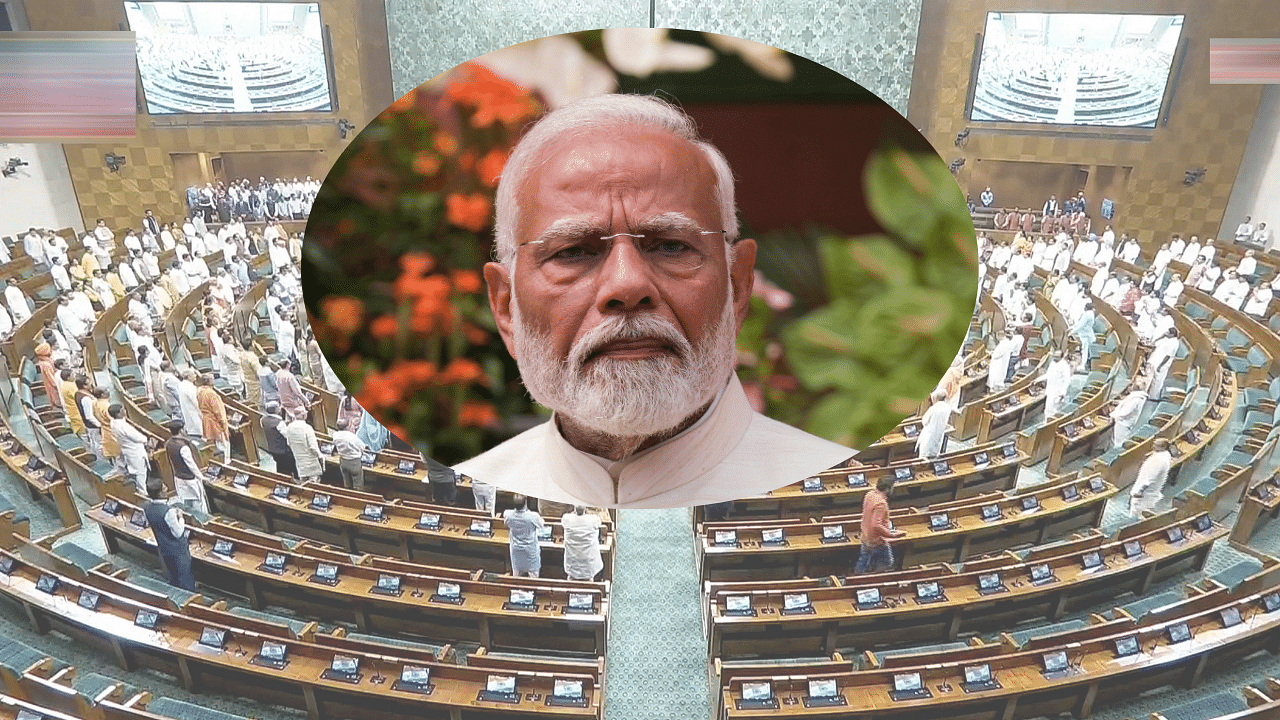

A collage showing Prime Minister Narendra Modi and members of the 18th Lok Sabha (in the background).

Credit: PTI Photos

By Swati Gupta and Ruchi Bhatia

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s vast domestic agenda is in jeopardy after his party failed to win an outright majority in parliament for the first time in a decade, forcing it to work with a coalition of parties and grapple with an expanded opposition bench.

Over the past decade that Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has ruled with absolute majorities, its advocated for — and pushed through — laws that critics say have furthered its divisive Hindu majoritarian goals. Some of the outstanding policies on that agenda may now need to be reviewed or jettisoned after the electoral setback.

Signs of acrimony between the BJP-led government and the opposition were visible Monday at the start of the first parliamentary session since election results earlier this month. A united opposition — which won about 230 of the 543 seats in the lower house, the Lok Sabha — are opposing the BJP’s selection of a temporary speaker of parliament and are protesting against a brewing scandal over college entrance exams.

Addressing the opening session, Modi appealed for consensus among lawmakers to meet ambitious goals of making India a developed nation by 2047.

“Together we will fulfill that responsibility and we will further strengthen the trust of the people,” Modi said. “We want to go ahead and speed up decisions by taking everyone together, by maintaining the sanctity of the constitution.”

The opposition alliance, led by the Indian National Congress, had accused Modi and the BJP of undermining the constitution. Opposition lawmakers led by the Congress party’s Rahul Gandhi held up copies of the constitution as they took their oath of office Monday.

“Our message is going across, no power can touch the constitution of India,” Gandhi told reporters.

Here’s a look at some of the BJP’s domestic policies that may now be in doubt, or need to be reworked under a coalition government.

Uniform Civil Code

For years, the BJP has advocated for the replacement of India’s religion-based laws with a uniform civil code. This would entail a non-religious set of rules governing issues like marriage, inheritance and divorce. Modi and his party have long championed for a uniform code. They see the current system as allowing non-Hindu communities — especially Muslims — to operate on their own terms, and a new code would likely outlaw many personal practices relating to marriage and divorce.

In a test case, the BJP-run northern Indian state of Uttarakhand passed the code in its state assembly earlier this year. Successive governments have stayed away from amending these laws out of fear of angering voters from all faiths. It’s likely Modi’s key regional allies — all of whom have substantial Muslim populations in their states — will shy away from siding with the BJP should they try and introduce the measure in the current parliament.

National Register of Citizens

A month before India’s elections kicked off in April, the government implemented a religious-based law — the Citizenship (Amendment) Act — which fast-tracks citizenship rights for immigrants from neighboring nations except for those who identify as Muslim.

The law was seen as a precursor for a proposed national citizenship register, which will require Indians to prove their citizenship. Amit Shah, who retained his position as home minister in Modi’s new cabinet, has previously promised to conduct a nationwide exercise to root out illegal immigrants from neighboring countries like Bangladesh, many of whom are Muslims.

In a country with poor literacy and high poverty, documentation is often hard to procure for many Indians and consequently citizenship harder to prove. Critics had feared that if the BJP had won a large majority — as many had predicted prior to the polls — the government would’ve likely pursued the national population register. However, a coalition government, in partnership with other state leaders, will likely force Modi to negotiate with his partners on any deal.

Military recruitment scheme

In 2022, the Modi government shifted the Indian army’s recruitment policy to short-term jobs with no pension benefits. The announcement of the scheme resulted in protests across the country as it further limited employment options in a country already grappling with a severe jobs crisis. Under the plan, the recruits would train for six months, serve in the military for three and a half years but will not be entitled to pensions or other benefits when they leave.

Leaders from two of the BJP’s partners in the eastern state of Bihar — which is also one of India’s poorest — have publicly asked for a review of the policy. During the election campaign, scrapping the scheme was one of the opposition’s main promises.

One Nation One Election

The Modi government is keen to revamp the country’s electoral system: It wants to hold simultaneous national and state elections. The government’s stance is that concurrent elections would cut costs and improve efficiency. A committee constituted by the government on the subject submitted its report in March and recommended that the government move to enact a “One Nation One Election” strategy.

At the moment, state polls are spread across the country’s five-year election cycle. For example, polls in the key states of Maharashtra and Haryana will take place later this year, just months after the country voted in national elections.

To implement the scheme, the government would need to amend the constitution, a task made considerably harder while governing with a coalition and against an opposition staunchly opposed to the proposal. Modi’s opponents have long feared that the BJP will use its national popularity to also sweep simultaneously-held state elections. Currently, off-cycle elections spread over a five-year period mean local issues — and parties — often dominating voter’s preferences.

Census and delimitation

India’s last census was conducted in 2011. The next one, due in 2021, was put on hold because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Last year, parliament passed a law requiring a census followed by a delimitation exercise, after 2026.

The last delimitation exercise, or redistricting, was conducted in 2002, with subsequent governments kicking the can down the road to not upset the current balance of seats in parliament.

Southern states, which have always lagged in terms of seat distribution — given their lower population — expect delimitation to further reduce their representation in India’s lower house of parliament, the Lok Sabha. The country’s populous northern states — many of them BJP strongholds — would almost certainly see their share of parliamentarians increase.

A fresh census and reshaping of the political constituencies will also pave way for Modi to implement the women reservation bill that sees a third of lawmakers’ seats reserved for females.

Affirmative action

Under India’s constitution, affirmative action is enshrined for socially and economically backward communities — including of lower caste Indians. A specific quota of government jobs and places in government-run educational institutions are reserved for those on the lowest rungs of the caste system under the policy.

Modi’s BJP lost support among lower caste Hindus in the latest election, with many of them voting for caste-based parties, especially in some key northern states.

In TV interviews and election rallies, Modi blamed the opposition for exploiting cleavages over the caste system to sway voters and repeatedly assured the country that the BJP would not scrap affirmative action policies. He also stressed that the BJP would never give affirmative action based on religion, specifically for Muslims.

Modi’s ally, the Telugu Desam Party does target some affirmative action program on the basis of religion where it rules in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh — making it an issue where the BJP will likely be at odds with a much-needed ally.