Earlier this month, nearly 70 children in The Gambia died, reportedly after consuming India-made cough syrups contaminated with toxic chemicals. Two years ago, doctors in Jammu encountered similar cases of kids dying from kidney failure after drinking cough syrup manufactured by Digital Vision, a Himachal Pradesh based company. Investigations revealed the presence of an industrial-grade solvent — diethylene glycol (DEG) — in the medicine. The solvent is not used for drug-making and is toxic to humans. The adverse effects of DEG have been known to the pharmaceutical industry since 1937. Yet, there have been at least five major cases of DEG poisoning in India since 1972.

Also Read | India's place in the global medical supply chain

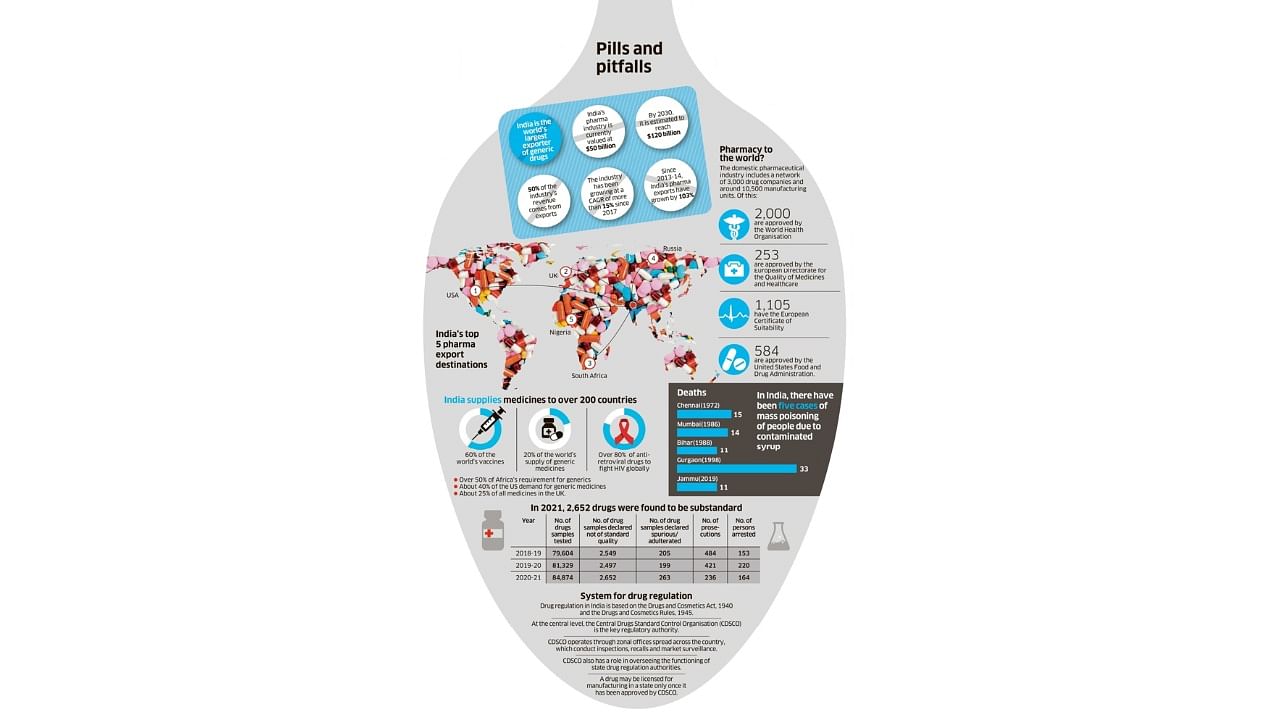

Five decades later, the World Health Organisation (WHO) once again flagged the presence of “unacceptable” levels of DEG and ethylene glycol in four cough syrups manufactured by Haryana-based Maiden Pharmaceuticals, which were exporting the medicines to the west African nation. The UN health body said the company had not provided any guarantee on the safety and quality of the products. With the WHO alert triggering an uproar, the Union Health Ministry asked Maiden Pharmaceuticals — a company with a tainted past — to stop all manufacturing activities. The government also formed an expert panel to investigate the entire episode and suggest a future course of action.

This, however, is too little, too late as the ministry is well aware of the deep-rooted ills of the Indian drug regulatory systems. What the WHO red flag has done, is turn the spotlight, once again, on the Central Drug Standard Control Organisation, which was described as an “Augean Stable” by a panel of lawmakers a decade ago. Pharmaceutical manufacturers enjoy the benefits of such an opaque system till a mishap occurs, as it did in The Gambia recently.

When officials from the Haryana Food and Drug Administration inspected Maiden’s manufacturing plant at Sonipat following the WHO alert, they found several discrepancies in the records, due to which the quality of the raw material could not be ascertained.

The firm could not produce the batch numbers of propylene glycol and sorbitol solution, as well as that of sodium methylparaben to the drug inspectors, making it impossible for them to trace the source of the chemicals and check their quality. The company did not check for contaminants like DEG and ethylene glycol in the solvent. It also failed to produce the in-process testing report of the products.

Experts are of the opinion that it is entirely possible for traders supplying the chemicals to mislabel DEG as propylene glycol or adulterate propylene glycol with DEG, either to reduce costs or due to poor quality control measures. “The company may not be using pharmaceutical-grade propylene glycol. If the company is not carrying out quality testing on the final product, it is doomed,” said S Srinivasan from All India Drug Action Network.

There are multiple other discrepancies in the quality checks of Maiden's four products. Now, pause for a moment and think about India's more than 10,000 pharmaceutical manufacturing units — of which more than 2,000 are WHO-GMP (WHO's Good Manufacturing Practice standards) certified — owned by 3,000 plus companies and the thousands of products they are manufacturing each day. How robust and reliable is the regulatory system to check their quality?

Serious discrepancies

In August 2013, on a routine investigation, drug inspectors in Tamil Nadu found that an anti-diabetic medicine Glipizide was “not of standard quality” as it did not actually contain Glipizide. Instead, the tablet contained another anti-diabetic medicine named Glibenclamide, which cannot be used as a substitute for Glipizide because the human body takes three to four hours longer to metabolise the drug. This puts people at serious risk as it increases the possibility of hypoglycemia in patients who unwittingly take one drug instead of another.

When the inspectors checked the production plant — Alfred Berg and Co was the manufacturer — they found shocking lapses, including the absence of a separate quality assurance department. The most critical records documenting the manufacturing process were not accessible to the drug inspectors, and in the records that were accessible, the inspectors reported several discrepancies. A court case filed against the company in December 2014 is yet to proceed to trial as of March 2022.

Maiden, Digital Vision and Alfred are not isolated examples. There are many such companies producing 'Not of Standard Quality' (NSQ) drugs. Some of these may be recalled from the market after quality tests, but many continue to thrive. Since some states, including Kerala and Maharashtra, have an active drug administration, there are also court cases against the producers of NSQ drugs. But in the absence of a centralised database, it's impossible to identify those still sold in the market.

"The entire quality check process is riddled with holes. We do not think about quality by design. We think about quality as a final product. Otherwise, how would you explain the fact that the entire Baddi region in Himachal Pradesh has around 690 pharmaceutical manufacturing units, as reported by a newspaper, but not a single functioning HPLC (high-performance liquid chromatography) machine to test their quality?” asks Dinesh Thakur, public health activist and founder of Citizens for Affordable, Safe and Effective Medicine, a non-governmental organisation.

Administrative impediments

The biggest impediment to improving the quality of pharmaceutical regulation is the existing legal and administrative structures of the Central Drugs Standard Control Organisation (CDSCO). Unlike other regulators like the Telecom Regulatory Authority of India and Food Safety and Standards Authority of India, the CDSCO does not have any statutory backing.

The CDSCO functions as a subsidiary of the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS). The Drugs Controller General of India (DCGI), who heads the CDSCO, is an officer low in the pecking order and is answerable to the DGHS, Health Secretary and Health Minister. In fact, the drug regulation division in the Health Ministry headed by a Joint Secretary-level officer wields more power, even though the division lacks technical knowledge and relies on the CDSCO.

“Such an administrative setup is completely antiquated and is not keeping with modern regulatory structures that have evolved post-liberalisation,” Thakur wrote in a letter to the Health Ministry, suggesting changes to the system of regulation.

An effort to initiate a change was made nine years ago, when the Drugs and Cosmetics (Amendment) Bill, 2013 was introduced in Parliament to create a Central Drugs Authority as an independent body. The draft law was framed on the basis of recommendations made by a 2003 Committee headed by then Council of Scientific & Industrial Research Director General R A Mashelkar. But the bill was never debated in Parliament and was ultimately withdrawn.

Need for transparency

The poor regulatory system is also plagued by a lack of transparency and the complex distribution of regulatory powers across 38 authorities (one in each state and union territory, and the CDSCO) without much oversight.

There is also no public database on violations, inspections and history of a brand. In the absence of such a system, it is impossible for a drug inspector in Assam to know if a particular medicine was banned in Punjab. The Food and Drug Administration of Maharashtra cannot raid a manufacturing plant in Himachal Pradesh as they lack jurisdiction, even if they are aware of NSQ drugs being produced at the plant.

"The CDSCO has to be transparent at every level. Drug inspection reports should be made public and there must be a database where reports from all 28 testing laboratories are made available to the public. Also, there has to be centralisation of the licensing and inspection function,” says T Prashant Reddy, a patent lawyer and co-author, along with Thakur, of The Truth Pill, a new title on India’s drug regulatory system. In the absence of such cross-links, medicines banned in one state can easily be sold in another state.

Examples of India’s poor regulatory standards are too many — from the approval of hundreds of irrational FDCs (fixed-dose combinations) to the questionable approval of the home-grown Covid-19 vaccine, Covaxin. The extent of the rot in the approval process came to light a decade ago, when the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health examined the CDSCO, inspecting records that were previously never made public.

The probe by the lawmakers brought out many skeletons hidden in the closet. The House panel cited multiple cases in which doctors located in different cities, thousands of miles away, wrote identical letters of recommendation. In one case, a Mumbai-based doctor wrote a recommendation letter on the same day he received the DCGI notice to comment on a proposal that contained 131 pages of scientific data to peruse. In another case, a CDSCO official asked a pharmaceutical company to select experts, get their opinions and deliver them to the DCGI’s office for the approval of an FDC that was not permitted in North America, Europe and Australia. All such cases, according to the panel, show that "there is sufficient evidence on record to conclude that there is collusive nexus between drug manufacturers, some functionaries of CDSCO and some medical experts."

The parliamentarians made recommendations to address these gaps. What the government did in response was perfunctory. The 'Action Taken' report, tabled by the government in April 2013, carried 29 pages of scathing remarks and observations by MPs on the Health Ministry. “The Ministry has abundantly proved that it has neither the intention to clean the Augean stables of CDSCO nor any concern for probity and rule of law,” the MPs wrote.

A year later, the Narendra Modi-led government came to power with a promise of change. “But hardly anything has changed in the CDSCO in the past seven years,” says an expert.

One of the consequences of the Maiden Pharma controversy was a legal notice served to Thakur and Reddy for publicly saying that the CDSCO could not escape responsibility for the Gambian episode. But there is no talk on the deep-rooted corrections that are required in India's regulatory system to put its house in order.