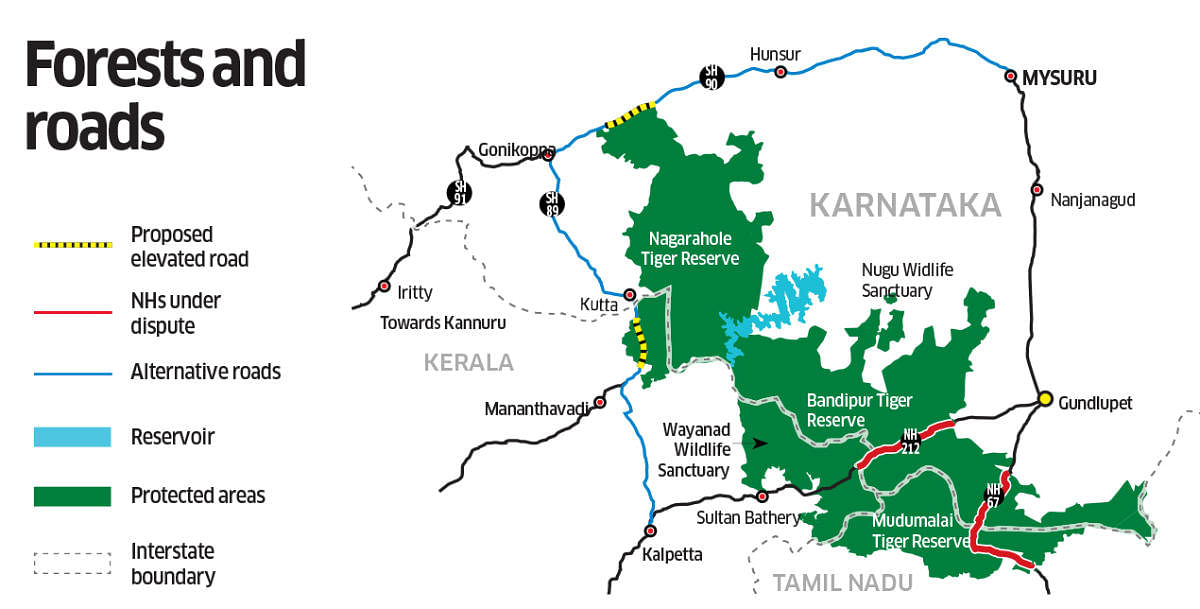

Eight years after night traffic on the NH 766 stretch through the Bandipur Tiger Reserve in Karnataka was banned, Kerala’s opposition continues to be pegged to one broad argument — that it inconveniences people who travel between its northern districts and the Mysuru-Bengaluru region. In a debate that traces wildlife conservation and serious ecological concerns, the inconvenience argument has been viewed by critics as a simplistic plank to take. Successive governments in Kerala have reiterated commitment to lift the ban and discussions with Karnataka have invariably hit roadblocks.

The 9 pm – 6 am ban has divided opinion across the border and consensus, at this point, appears elusive. The government has cited opposition by traders in Wayanad while arguing against the ban. The longer, alternative route (Hunsur – Gonikoppal – Kutta – Mananthavady) is being used by many but traders point out that it’s more about lack of choices than the actual endorsement of the alternative.

Johnny Pattani, president of the Wayanad Chamber of Commerce, said businesses in the district were severely hit because the movement of goods was restricted during crucial night hours. “Trade enquiries have continued to drop. The business of black pepper, ginger and other produce from the district has suffered. This has gone for too long; the new proposal (by the Ministry of Road Transport and Highways - MoRTH) for elevated corridors in the stretch is something that could at least be looked at,” Pattani said. A spice trader based in Vythiri in the district agreed that lifting the ban would ease business but said he had moved on and would rather find alternative resources than wait for government-level discussions to make headway.

“The alternative road is not an alternative at all. It passes through a different region that now has increased vehicular traffic, posing similar dangers to wildlife,” Tiji Cheruthottil, convenor of Freedom to Move, a collective that campaigns against the ban, said.

P S Easa, former head of the Kerala Forest Research Institute and member of the National Board for Wildlife, is among experts who dismiss the MoRTH proposal for elevated corridors, citing irreparable damages to the habitat. The experts’ call to governments to look at the bigger picture and arrive at a balanced approach has not been addressed. A senior forest official in Wayanad said he could not comment on the issue because as part of the administration, he was bound by state policy.

C K Saseendran, the CPM MLA from Kalpetta, said the Left government would continue to have people at the centre of its argument in the case. “We are sensitive to concerns over roadkill and wildlife conservation but no deliberation on environment can take people out of the equation,” the MLA said. Towns including Sultan Bathery and Kalpetta have very early shutdowns since the ban, Sultan Bathery MLA I C Balakrishnan said. He said it was important to identify and isolate real estate groups that try to cash in on proposals for alternative roads. Environmentalists in the state feel that an inability, on both sides, to go beyond administrative compulsions has doubled as a deadlock.

Members of the Nilgiri-Wayanad NH and Railway Action Committee, which demands the lifting of the ban, said Kerala’s argument itself was marked by contradictions. “The state government has never stepped back on its demand for lifting the ban which is in line with views of the people as well. At the same time, we’ve had senior forest officials who called for an extension of the restricted hours. This amounts to going against the state policy,” T M Rasheed, convenor of the committee, said.

Traders in Wayanad and Kozhikode also feel that governments have failed in mobilising their dissent and devising an inclusive, viable strategy to lift the ban. Some of them point out that courts were not “properly” apprised on threats in developing more alternative roads, including the rise of real estate interests in the ecologically sensitive region and the roadkill reported on these roads.

Balakrishnan, proprietor of a fruit and vegetable store in Sultan Bathery, said business from Karnataka which constituted a major share of his revenues was on a breakdown. “For someone packing fruits and vegetables from the Karnataka side, losing the night hours is crucial. For traders like us who then supply these products to other parts of Kerala and outside, it becomes even more difficult. Delayed delivery affects quality of items like bananas and papayas,” Balakrishnan said.

Cheruthottil feels that the Supreme Court’s appointment of an expert committee, including representatives from both states, showed direction towards consensus but Kerala, despite its official position against the ban, is failed by bureaucrats who endorse a contradicting line. “The debate should be centred on the right to move freely. We have enough expertise to ensure that the right is safeguarded, without impacting the wildlife. All it takes is political will,” he said.