By Archana Chaudhary, Sudhi Ranjan Sen and Bibhudatta Pradhan

As India recorded more than 234,000 new Covid-19 infections last Saturday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi held an election rally in the West Bengal town of Asansol and tweeted: “I’ve never seen such huge crowds.”

The second wave of the coronavirus has since grown into a tsunami. India is now the global coronavirus hotspot, setting records for the world’s highest number of daily cases. Images of hospitals overflowing with the sick and dying are flooding social media, as medical staff and the public alike make desperate appeals for oxygen supplies.

The political and financial capitals of New Delhi and Mumbai are in lockdown, with only the sound of ambulance sirens punctuating the quiet, but there’s a growing chorus of blame directed at Modi over his government’s handling of the pandemic.

Modi canceled another planned appearance in West Bengal on Friday to hold meetings on the pandemic response. Whether it’s enough to prevent the political fallout may become clear on May 2, when election results are due to be announced for the five states voting over the last month: West Bengal, Assam, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Puducherry.

“At this crucial time he is fighting for votes and not against Covid,” said Panchanan Maharana, a community activist from the state of Odisha, who previously supported Modi’s policies but will now look for alternative parties to back. “He is failing to deliver — he should stop talking and focus on saving people’s lives and livelihoods.”

Modi is seen by many as a polarizing leader whose brand of nationalism that promotes the dominance of Hindus has appalled and enraptured the nation. Despite policy stumbles in his first term, voters re-elected him in a landslide in 2019 in the absence of any viable opposition. In the last poll taken in January, during a lull in the epidemic, his popularity was 74 per cent, down a touch from 78 per cent last August but still impressively high. Whether the pandemic will dent his appeal remains unclear.

“There is no doubt an outpouring of anger at the mismanagement of the Covid-19 crisis in India,” said Nikita Sud, who teaches international development at the University of Oxford and has published a book on Hindu nationalism. “The question is, will this anger trump the hate that has been systematically sown in our society for years? And will public memory last long enough for the pandemic-related anger to be manifested at election time?”

Those are not easy questions to answer.

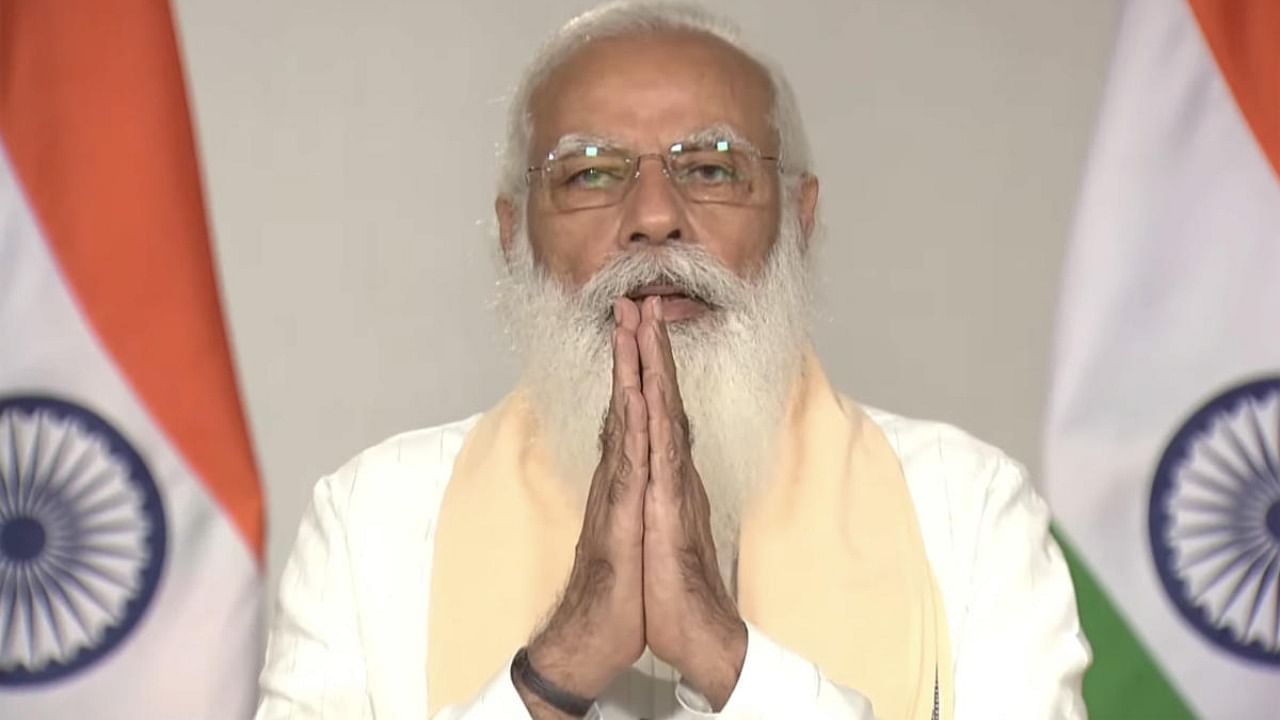

Judged by the outpouring of criticism on Twitter, the anger and disappointment in India’s leader is manifest. When Modi addressed the nation on Tuesday, it seemed that he had failed to grasp the growing sense of panic among citizens. As he spoke, without providing any details on how his government would turn the situation around, the Hindi hashtag that translates as “Stop the speech, not the oxygen” was tweeted more than 108,000 times. Other hashtags, including #ModiMadeDisaster and #ModiResign were also popular.

Footage of Modi, unmasked, addressing huge crowds who were also mostly without masks or social distancing, stood in stark contrast to images of exhausted doctors and nurses desperately trying to create more capacity in the country’s decrepit, underfunded health system.

Noting that at least six high courts are hearing disputes about Covid-19 management including oxygen shortages, the Supreme Court on Thursday asked the federal government to come up with a national plan for the distribution of essential supplies and services.

Yet it is far from guaranteed that the current crisis will cost Modi at the ballot box. For his followers, the government’s support for building a Hindu temple in Uttar Pradesh on the contested site of a former mosque and its move to abolish the special status of Jammu and Kashmir — the only Muslim majority region in India — are far more pressing priorities. Hindus make up 80 per cent of the population.

“The construction of the temple is important for us, why can’t Hindus build a temple in our own land,” said Govind Kumar, a factory worker, as he sat with his meager belongings at a Delhi bus station on Tuesday, waiting to return to his village in Uttar Pradesh after the capital went into lockdown. Of the pandemic, he said: “Nobody can control the situation, why only blame Modi?”

It’s a sentiment expressed widely in India. Some commentators attribute the support for Modi as akin to that of a messianic figure whose appeal goes beyond mere politics. Asim Ali of the Centre for Policy Research in New Delhi, writing in The Diplomat on April 1, said that “Brand Modi seems to have escaped into the political stratosphere, untouched by the conventional laws of political competition.”

There are signs elsewhere that the pandemic may be too much for even the most populist of leaders to remain unaffected. President Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil confounded his skeptics by maintaining his base despite dismissing the pandemic, only to be forced into concessions when cases soared this year. Donald Trump could arguably have won a second term in November if it wasn’t for the US Covid-19 death toll, still the world’s highest.

Modi’s decision to hold election rallies and green-light large religious gatherings in the face of a growing second wave “will not inspire confidence about India’s leadership and governance record in any objective observer or investor,” said Sud of Oxford.

And India’s economy, which was showing nascent signs of recovery after falling into recession last year for the first time in decades, is now struggling again. As more cities and states have issued stay-at-home order or other movement restrictions, job losses have begun to tick up. Urban unemployment jumped to 10.72 per cent for the week ending April 18 from 7.21 per cent two weeks ago, according to data from the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy.

The prime minister is also under fire for over-promising on India’s vaccination rollout, both domestically and globally, after he dubbed the South Asian nation the “pharmacy to the world” last October. As case numbers soared, India suddenly halted its exports, which were a critical part of Covax, the World Health Organization program to provide inoculations to low income countries. Only last month his administration declared that the pandemic was in its end game.

After administering more than three million doses a day earlier this month, vaccine centers are now running out of doses and have shut down across many states, including the mega-city of Mumbai. On April 19, Modi announced changes to his government’s immunization strategy — opening the program up to everyone over 18 and allowing state governments to tailor their own strategy and procure directly from manufacturers. His critics fear it is intended to leave the states with the blame.

“In the first phase, Modi touted that they were in control and took credit,” said Sanjay Kumar, an election expert and co-director at Lokniti-Centre for the Study of Developing Societies in New Delhi. “Now people won’t buy their argument, they will blame Modi and his government.”

Still, Modi changed gear on Wednesday, tweeting about monitoring India’s depleted oxygen supplies and sending condolences and get well messages to public figures falling sick or dying. On Friday, he planned to “review the prevailing Covid-19 situation.”

He has a track record of successfully deflecting blame for policy failures. That includes demonetization in 2016 where he banned 86 per cent of the country’s currency overnight and left the economy and India’s citizens reeling, according to Katharine Adeney, director of the University of Nottingham Asia Research Institute.

“It will be easy for him to blame other political actors such as state governments and chief ministers if that suits his purpose,” Adeney said.